As the U.S. economy began recovering from coronavirus-related shortages and shutdowns, consumer prices surged faster than they had in more than four decades. Many Americans currently see inflation as one of the nation’s top problems.

The government gauges inflation mainly by looking at the prices of a “market basket” of more than 200 goods and services and evaluating how they’ve changed over time. Several inflation measures are based on this price data, but the most widely cited is the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U). Since the start of 2020, that measure topped out at 9.1% in June 2022 – the fastest year-over-year increase since November 1981.

Since the June 2022 peak, inflation has abated considerably. The CPI-U in June 2024 was just 3.0%, closer to the Federal Reserve’s 2% inflation target. That’s led to increased speculation that the Fed may start cutting interest rates soon.

But that doesn’t necessarily mean prices are going back down – just that they’re rising more slowly than they had been. Most things cost considerably more than they did before the COVID-19 pandemic. And the focus on the topline number can obscure the reality that inflation for individual items can be considerably above – or below – the “official” rate.

With all that in mind, we wanted to take a closer look at the CPI-U, and at the 200-plus products and services that go into that headline inflation number.

Pew Research Center conducted this analysis to learn more about which consumer goods and services drove the recent coronavirus-era inflation surge in the United States.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the arm of the U.S. Labor Department that tracks inflation, collects price data and calculates price indices for more than 200 product and service categories. These categories range from apples and airline fares to wine, window coverings and wireless phone services. The BLS weights each one to reflect its share of overall consumer purchases, combines them into an “all items” inflation index and reports it monthly.

We wanted to examine the price behavior of each of those items, so we downloaded monthly index values for all the ones the BLS makes public. (The agency withholds a few, mainly because data is missing or doesn’t meet its publication standards. Our group of 250 items accounts for about 96% of the overall CPI.)

The most typically reported inflation figures are the 12-month rates – the change in the price index between, say, June 2023 and June 2024. However, prices can remain elevated even if the rate at which they’re rising has slowed, and analysts say high prices continue to weigh on consumer sentiment. For that reason, we used the monthly index values for each item to calculate overall price changes since January 2020. (We chose that month as a baseline both because it was the start of the year and because the COVID-19 pandemic had not yet disrupted life in the United States in a major way.)

For gasoline prices, which are particularly visible to consumers, we supplemented the BLS data with weekly “all grades” pump price data from the Energy Information Administration, the U.S. Energy Department’s statistical agency.

Which goods and services have gotten more – or less – expensive in recent years?

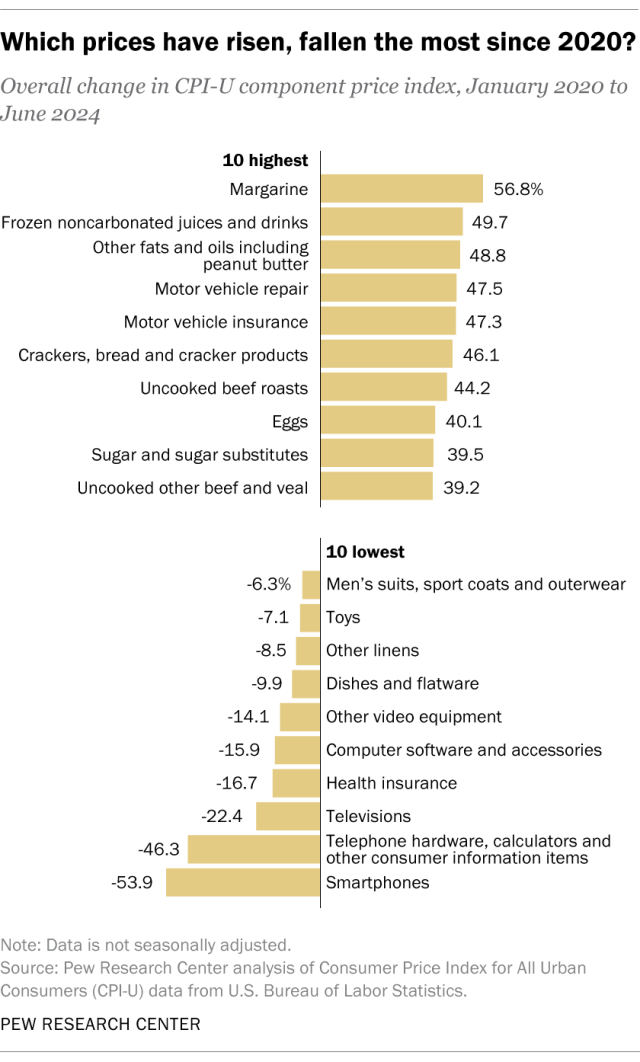

Overall, the June 2024 CPI-U was 21.8% above its level in January 2020, before the pandemic really began to hit the United States. But the costs of many products and services have risen much more than that.

Topping the list: margarine, which as of June is 56.8% pricier than in January 2020. Other notable increases include motor vehicle repair services (up 47.5%), motor vehicle insurance (47.3%) and veterinarian services (35.6%).

On the other hand, some goods and services cost less now than before the pandemic. For example, men’s suits, sport coats and outerwear are 6.3% cheaper than in January 2020. And dishes and flatware are down 9.9%.

Many of the items with the biggest price declines are related to computers, smartphones or other technologies. In these and other cases, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) – which puts together the CPI-U and related indices – adjusts the raw price data it collects to account for product improvements or other changes in quality over time.

In 2007, for example, the first-generation iPhone from Apple cost $499 (or $599 for the 8-gigabyte version) and came without many features that users today take for granted. Today, the 128-gigabyte base version of the iPhone 15, which is far more powerful and functional, retails for $799. Other smartphones have seen similar quality leaps over time.

The price index for smartphones has fallen 53.9% between January 2020 and June 2024. That essentially means that buying a smartphone today with the functionality that was typical in early 2020 would cost you less than half what it would have then.

What items carry the most weight in the CPI-U?

The hundreds of goods and services in the CPI-U aren’t all given equal weight when calculating the index. Instead, the BLS weights each item to reflect its share of overall consumer purchases.

The biggest item in the CPI-U, accounting for about a quarter of the entire index as of May 2024, is “owner’s equivalent rent of a primary residence” (OER). This arcane-sounding term basically estimates how much it would cost to rent out an owned home. It’s an attempt to separate a house’s value as shelter (which is treated as a service in the CPI-U) from its value as an investment (the increase in its market value over time), since investments aren’t included in the CPI-U.

OER inflation peaked at 8.1% in spring 2023 and still came in at 5.4% in June 2024. Overall, OER prices are 23.8% above their January 2020 level – just a hair below rental inflation, which is up 24.0%. Rental prices are the second-biggest factor in the CPI-U at about 7.6% of the total index.

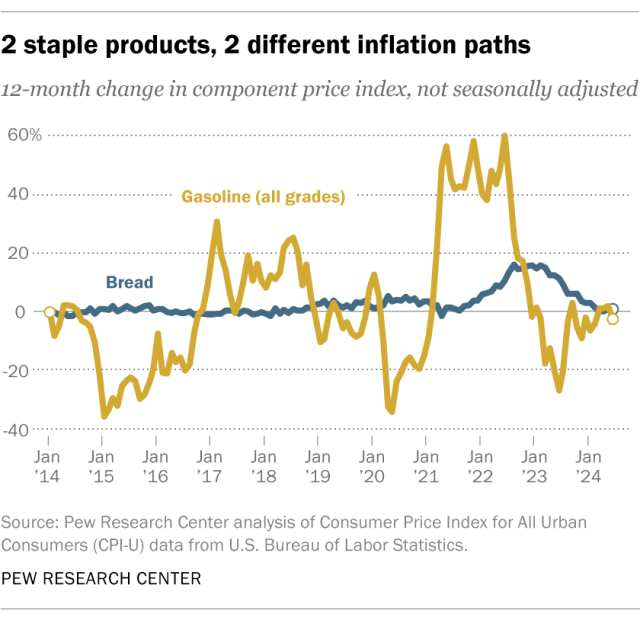

For many items, prices tend to rise or fall gradually, or at best, level off. Bread prices, for instance, seldom changed by more than a few percentage points annually from 2014 until early 2020 – though they jumped in 2022. But some items are far more volatile, with unpredictable surges and steep declines.

Gasoline, the third-biggest contributor to the CPI-U at about 3.6% of the index, is a prime example. Pump prices fluctuate based on the time of year, geopolitical events, refinery operations and a host of other factors.

Overall, the price index for all grades of gasoline was 35.9% higher in June 2024 than it was in January 2020. But that hides considerable volatility. From January 2020 to June 2022, gas prices nearly doubled (an 89.5% increase), but since then, they’ve fallen 28.3%. In fact, for all of its ups and downs, the average nationwide gas price at the end of July 2024 ($3.598 a gallon) was about what it was in early August 2014 ($3.595), according to data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

Which items have seen particularly sharp price spikes since 2020?

The 89.5% run-up on gasoline of all grades was almost the biggest of the pandemic period. But the price index for fuel oils (such as home heating oil) rose slightly more – 91.0% – between January 2020 and June 2022 before dropping. As of this June, fuel oil prices were 22.2% above their January 2020 levels.

The product with the sharpest (but short-lived) price spike over the past few years has been the humble egg. Egg prices peaked in January 2023 at 94.0% above the January 2020 baseline. Even though prices have fallen since, eggs still are about 40.1% more expensive than they were before the pandemic.