The most recent shooting involving a Toronto high school student this October highlighted a rising problem with gun violence in North American schools. In Canada’s largest city, it raised alarms about how the crisis is getting worse and skewing younger.

The recent tragedy is reminiscent of other high-profile shootings within Toronto high schools. In 2007, 15-year-old high school student Jordan Manners was fatally shot at school. In the years since Manners’s death, numerous recommendations on gun violence came out of reports and committees. However, little has been done to improve the danger of gun violence for Toronto teens.

To make things better, policy conversations about gun violence need to shift. They need to expand beyond the person behind the gun and gun regulation and move towards trauma-informed community programming that dismantles systemic barriers and inequities.

Risk factors that lead young people to violence

Many studies indicate that problems like poverty and unemployment are major risk factors that increase the likelihood of an individual gravitating towards gun violence.

In Canada, only one in five children who need mental health services receive them. A 2018 report by People for Education found that in Ontario there was on average only one in-school guidance counsellor for every 396 students. Trauma and a lack of attention to it also leads to having intergenerational impacts.

Last year, there were 277 firearm homicides in Canada. According to a recent report by The Centre for Research & Innovation for Black Survivors of Homicide Victims (CRIB), racialized Ontarians account for 75 per cent of Canadian gun homicide victims; 44 per cent of those victims belong to African, Caribbean or other Black communities.

If we do not improve standards of living and create genuine opportunities in communities, the cycle of poverty, violence and crime will continue.

Gun violence can be reduced with a strategy focused on deterrence

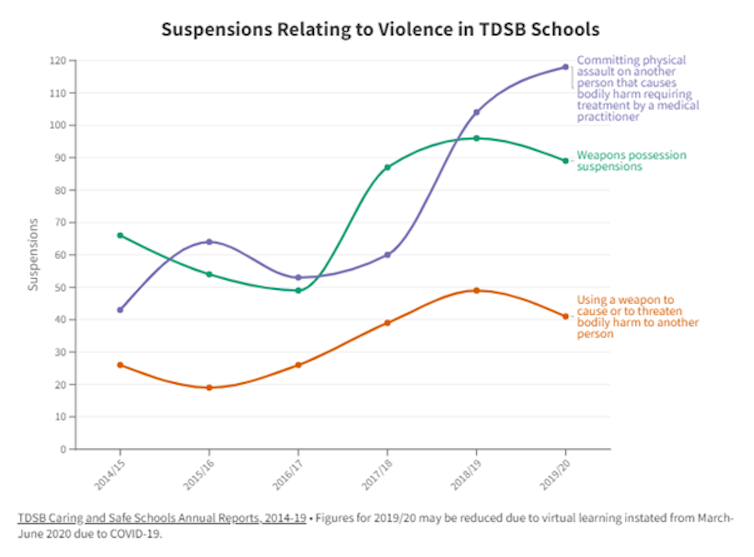

(TDSB), Author provided

Disrupting the school to prison pipeline

Education is one of the most effective protective factors in aiding reintegration and mitigating recidivism after release from prison.

There needs to be an ideological shift about the purpose of prisons. They should not be places that punish people by incarcerating them, but spaces that promote their rehabilitation.

As outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, education is a human right that should be upheld for everyone. That right extends to individuals who are incarcerated.

To see where we are with this, the Canadian Civil Liberties Association conducted 50 interviews with youth (ages 12-17), staff and teachers at detention facilities and justice system professionals to explore education for youth in detention and the barriers they face.

They found that “facilities were treating youth as security threats to be managed, rather than students deserving of rehabilitation through educational opportunities”.

It costs the Correctional Service of Canada an average of $111,202 per year to incarcerate one man (and twice as much to incarcerate one woman), with only $2950 of that money spent on education per prisoner.

There is a lack of capacity within incarceration institutions to meet educational demands. And there is a lack of partnerships with school boards and post-secondary institutions to offer education in prisons.

That lack of access to education is highly problematic given that the majority of people incarcerated do not have a high school diploma or its equivalent.

Harm reduction

A lack of mentorship and culturally relevant, responsive and sustaining education leads to many minoritized identities being pushed out of schools due to the content, policies, and teaching of schools not being reflective of their identities, histories or lived experiences.

For example, 80 per cent of school suspensions in Toronto are given to male students. Indigenous, Black, Middle Eastern and mixed-race students are over-represented in the suspensions and expulsions relative to their overall representation within the TDSB student population.

To counter this, there needs to be culturally relevant and responsive curriculum content and teaching to support learners and their families in relation to larger unmet needs at the community level.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Frank Gunn

Police and prevention

If Canada is going to become the egalitarian role model it aims to be on the world stage, the over-policing of racialized communities across the country must end.

Instead, more resources and emphasis on community-based intervention and prevention projects must be adopted such as Toronto’s TO Wards Peace and Public Safety Canada’s Peace Core New Narrative.

Both initiatives propose a public health approach rooted in supporting access to opportunities across different sectors. The projects were spearheaded via collaboration between different levels of government, community agencies and non-profits including Youth Association for Academics, Athletics, and Character Education (YAAACE) in Jane and Finch and Think 2wice in Rexdale in Toronto. These are projects I am also involved in. In fact, I started as a youth counsellor at YAAACE when I was 17.

TO Wards Peace (TWP) is a community-centric interruption model that features frontline “violence disruption workers.” These folks have lived experience and deep community connections which strengthens their capacity to build rapport with communities. In this way, they may be able to intervene peacefully and constructively, even in seriously violent or escalating situations.

At YAAACE, another initiative features “Community Resource Engagement Workers” supporting those impacted by the justice system (people who have been released from incarceration or are incarcerated) to use their strengths in pursuing healthy lifestyle choices and building life skills. This involves access to programming and connecting people with needed social support services in a timely manner.

A recent pledge by the Canadian government to fund community programs such as those mentioned above is a step in the right direction.

Canada needs to start putting the “human” back into the way it treats, responds to and serves marginalized communities.

Evie Mae Stevenson, a 3rd year undergraduate student who worked at YAAACE, helped write this article.