With early voting set to open next week for the Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum, this is a critical time for campaigners to win over voters.

If the 2022 federal election is anything to go by, Australians have developed a taste for early voting, with fewer than half of all voters actually going to a polling station on election day.

If the same voting patterns apply to the referendum, this means more than half of Australians, particularly older voters, may have cast a vote before voting day on October 14.

What’s happening in the polls?

Public polls indicate support for the “yes” campaign continues to decline, despite, as we’ve shown below, huge spending on advertising and extensive media coverage of its message.

According to Professor Simon Jackman’s averaging of the polls, “no” currently leads “yes” by 58% to 42% nationally. If this lead holds, the result would be even more lopsided than the 1999 republic referendum defeat, where the nationwide vote was 55% “no” to 45% “yes”.

The rate of decline in support for “yes” continues to be about 0.75 of a percentage point a week. If this trend continues, the “yes” vote would sit at 39.6% on October 14, 5.5 percentage points below the “yes” vote in the republic referendum.

If “yes” were to prevail on October 14, it would take a colossal reversal in public sentiment, or it would indicate there’s been a stupendously large, collective polling error. Or perhaps both.

What’s happening in the news and social media?

Using Meltwater data, we have seen a massive spike in Voice media coverage since Prime Minister Anthony Albanese announced the referendum date at the end of August.

In the most recent week we analysed, from September 14-21, we saw a huge jump of mentions of the Voice to Parliament (2.86 million) in print media, radio, TV and social media. This compares to about a quarter million mentions in the first week of the “yes” and “no” campaigns, which we documented in our last report of this series monitoring both campaigns.

The ‘no’ campaign is dominating the messaging on the Voice referendum on TikTok – here’s why

Voice coverage now constitutes 6.7% of all Australian media reporting, up from 4.2% in week one. To put that in perspective, mentions of Hugh Jackman’s marriage split from Deborra-Lee Furness comprised 1.5% of total weekly coverage, while mentions of the AFL and NRL amounted to 4.1% and 1.7%, respectively.

Media coverage of the Voice peaked on September 17 with 38,000 mentions, thanks to widespread coverage of the “yes” rallies that day around the country.

This was followed closely by 35,000 Voice mentions the next day, led by Opposition Leader Peter Dutton’s claim on Sky News that a Voice to parliament would see lawyers in Sydney and Melbourne “get richer” through billions of dollars worth of treaty negotiations.

Our analysis of X (formerly Twitter) data provides further insight to these trends, showing the nationwide “yes” rallies on September 17 received the most public engagement about the Voice during the week we analysed.

Author provided

Who is advertising online?

This week, we specifically turned our attention to the online advertising spending of the campaigns. We also examined the types of disinformation campaigns appearing on social media, some of which are aimed at the Australian Electoral Commission, similar to the anti-democratic disinformation campaigns that have roiled the US.

The main online advertising spend is on Meta’s Facebook and Instagram platforms. We have real-time visibility of this spending thanks to the ad libraries of Meta and Google.

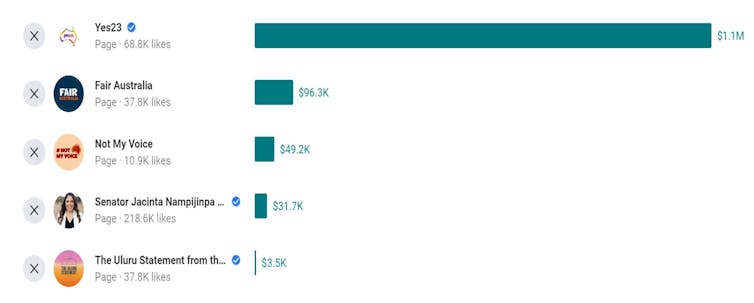

The Yes23 campaign has far outspent any other Voice campaigner on these platforms. In the last three months, its advertising expenditure exceeds $1.1 million, compared to just under $100,000 for Fair Australia, the leading “no” campaign organisation.

Meta ad library

Yes23 has also released a far greater number of new ads in September (in excess of 3,200) on both platforms, compared to Fair Australia’s 52 new ads. The top five spenders from both sides are listed below.

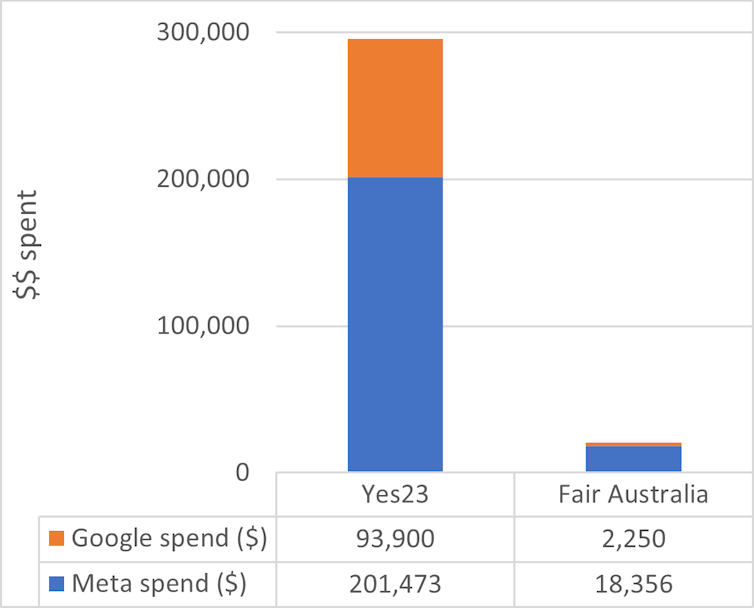

As early voting nears, this graph shows Yes23 ad spending outpaced Fair Australia on both Google and Meta platforms in week three, as well.

Authors provided.

The advertising spending data shows how drastically different the strategies of the two main campaigns are. Yes23’s approach is an ad blitz, blanketing the nation with hundreds of ads and experimenting with scores of different messages.

In contrast, the “no” side has released far fewer ads with no experimentation. The central message is about “division”, mostly delivered by the lead “no” campaigner, Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price. All but eight of the ads released by the “no” side in September feature a personal message by Price arguing that the referendum is “divisive” and “the Voice threatens Aussie unity.”

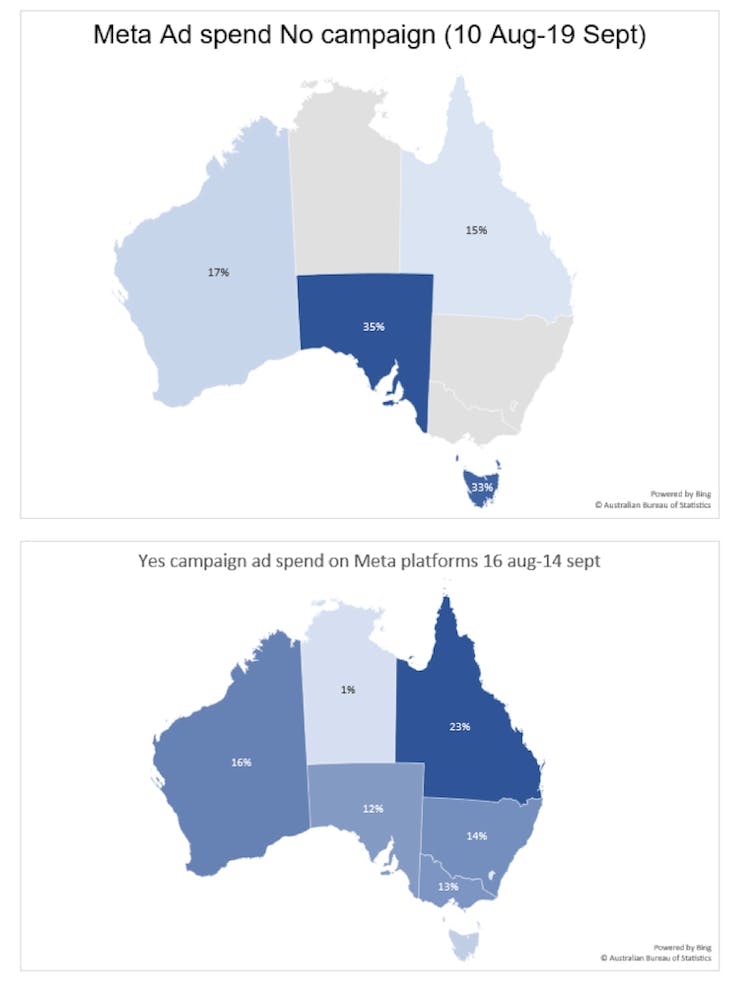

To win, “yes” requires a majority of voters nationwide, as well as a majority of voters in a majority of states. The “no” side is strategically targeting its ads to the two states it believes are most likely in play – South Australia and Tasmania. It only needs to win one of these states to ensure the “yes” side fails.

Author provided

Referendum disinformation

The Meltwater data also reveal a surge in misinformation and disinformation targeting of the AEC with American-style attacks on the voting process.

Studies show disinformation surrounding the referendum has been prevalent on X since at least March. To mitigate the harms, the AEC has established a disinformation register to inform citizens about the referendum process and call out falsehoods.

We’ve identified three types of disinformation campaigns in the campaign so far.

The first includes attempts to redefine the issue agenda. Examples range from the false claims that First Nations people do not overwhelmingly support the Voice to conspiracy myths about the Voice being a globalist land grab.

These falsehoods aim to influence vote choice. This disinformation type is not covered in the AEC’s register, as the organisation has no provisions to enforce truth in political advertising.

Why is it legal to tell lies during the Voice referendum campaign?

The register does cover a second type of disinformation. This includes spurious claims about the voting process, such as that the referendum is voluntary. This false claim aims to depress voter turnout in yet another attempt to influence the outcome.

Finally, a distinct set of messages targets the AEC directly. The aim is to undermine trust in the integrity of the vote.

A most prominent example was Dutton’s suggestion the voting process was “rigged” due to the established rule of counting a tick on the ballot as a vote for “yes”, while a cross will not be accepted as a formal vote for “no”. Sky News host Andrew Bolt echoed this claim in his podcast, which was repeated on social media, reaching 29,800 viewers in one post.

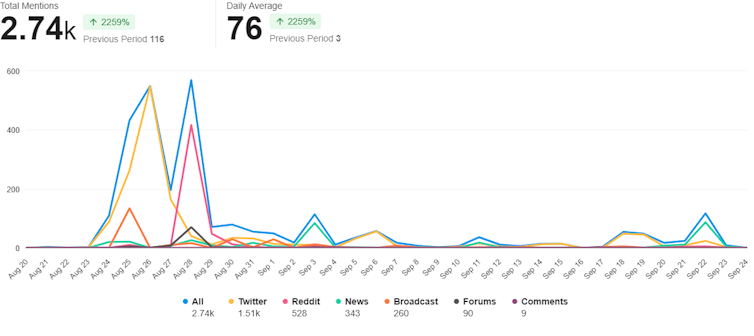

Attention to the tick/cross issue spiked on August 25 when the AEC refuted the claim (as can be seen in the chart below). Daily Telegraph columnist and climate change denialist Maurice Newman then linked the issue to potential voter fraud, mimicking US-style attacks on the integrity of voting systems.

Authors provided

The volume of mentions of obvious disinformation on media and social media may not be high compared to other mentions of the Voice. However, studies show disinformation disproportionately grabs people’s attention due to the cognitive attraction of pervasive negativity, the focus on threats or arousal of disgust.

All three types of disinformation campaigns attacking this referendum should concern us deeply because they threaten trust in our political institutions, which undermines our vibrant democracy.