This article references antiquated language when referring to First Nations people. It also mentions names and has images of people who may have passed away.

Before the end of this year, Australians will vote on enshrining an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice in the nation’s constitution. Referendums are famously fraught, and both advocates and detractors of the Voice have drawn comparisons to the 1967 referendum, the nation’s most successful to date.

Then, 90.77% of Australians endorsed two constitutional amendments. One removed Section 127, whereby “Aboriginal natives” were not counted when “reckoning the numbers of the people of the Commonwealth”. The second altered Section 51 (xxvi) – the race power – to allow the Commonwealth to make “special laws” concerning Aboriginal people.

Why was this campaign so successful? Today commentators largely put it down to unanimity: there wasn’t a “no” campaign in 1967. This is one of the reasons, no doubt, but as historians often say: “it’s complicated”. Deconstructing the mythology that surrounds the vote provides a fuller answer.

The history of referendums in Australia is riddled with failure. Albanese has much at risk – and much to gain

The road to referendum

Indigenous and settler scholars have long questioned the accepted narrative around 1967. The Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders, founded in 1958 with the purpose of fighting for constitutional change, had a big role in shaping the referendum’s meaning. The council first fought a petition campaign in 1962-3, and the vote itself, on the basis that a “yes” victory would grant citizenship rights for Indigenous people.

This was only ever partly true. The same activists who led the council’s campaign, including feminist Jessie Street, communist and scientist Shirley Andrews, Quandamooka poet Oodgeroo Noonuccal (Kath Walker) and Faith Bandler, an activist of South Sea Island and Scottish-Indian heritage, had already fought for and won many of the trappings of citizenship.

Voting rights, for instance, were secured federally in 1962, and in every state by 1965. And while various state acts continued to limit movement and alcohol consumption for the people under their so-called “protection”, constitutional alteration in itself would do little to change this. By giving the federal government powers to override state laws, it was hoped, pressure from within and without would lead to the end of official discrimination.

The ‘wind of change’

The long, conservative government of Robert Menzies had stone-walled moves to hold a referendum, at least partly owing to a desire to maintain Section 51 unamended. That the Commonwealth would make “special laws” for Indigenous people ran counter to the goal of assimilation. Menzies’ successor, Harold Holt, was more amenable.

Holt’s progressive agenda – as well as supporting the referendum, he removed discriminatory provisions from the Migration Act – signalled his difference from Menzies to a changing electorate. But he and his ministers were also looking internationally. British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan’s 1960 declaration that a “wind of change” was sweeping away racial discrimination and colonial domination had an Australian echo.

The 1965 “Freedom Rides” had done much to highlight continued apartheid-style practices in rural Australia. And during the Cold War, Australia’s overseas perception carried substantial weight.

Indigenous rights activists had long warned that Australia needed to act on issues of discrimination, with anti-colonial sentiment widespread in Asia, and the quickly growing United Nations watching. Liberal parliamentarian Billy Snedden hoped that removing mention of “Aborigines” from the constitution would also “remove a possible source of misconstruction in the international field”.

Right wrongs, write yes!

While reflective of international sensitivities, the 1967 referendum was hardly a rejection of assimilation policy. Indeed, the Federal Council’s slogan of “black and white together” can be read as a reflection of integrationist ideology: the goal of “Aboriginal advancement” was to live on white terms.

State Library of South Australia

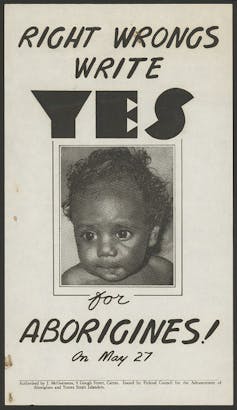

The campaign materials used in support of the referendum, much of which was produced by the Federal Council and distributed via trade unions and community organisations, reflected a simple message of unity and national absolution. Perhaps the most famous leaflet of the campaign – “Right Wrongs, Write Yes!” in large lettering, alongside an image of an Indigenous child – elevated the message above politics. The wrongs of the past could be done away with at the stroke of a pen.

The resounding victory was indeed read as a vindication of the decency of Australians. As one commentator put it:

The politicians were proud, the priests popular, the promoters propitiated, the public pleased. Being party to the most overwhelming referendum victory in the history of the Commonwealth of Australia demanded self-congratulation and the bestowal of bouquets upon all.

Current Prime Minister Anthony Albanese was channelling similar sentiments earlier this month, declaring the Voice referendum offered a chance for Australians to show their “best qualities”. It would, he said, “be a national achievement in which every Australian can share”.

1967 shows us the power that such unifying language can have, but also that unanimity can conceal inertia.

‘Advocated by all thinking people’

This sense of national duty and righting wrongs at least partly explains why opposition to the proposed changes in 1967 was muted. Adelaide’s Victor Harbour Times captured the tenor: “a Yes vote is advocated by all thinking people”. But this opinion, much like today, was not unanimous.

Despite the lack of a formal campaign, the West Australian newspaper ran a particularly hard “no” line. Fears of creeping Commonwealth power over “state rights” were propounded, as was the referendum’s lack of detail. “It was a pity that this issue was not worked out in advance”, one article bemoaned, for then “the people could have been presented with a firm, rational policy”.

Western Australia registered the highest “no” vote of any state at the referendum, at close to 22%. This reflects at least in part this editorialising. Post-referendum analysis also indicated that racist attitudes shaped voting patterns. The greater the proximity to an Aboriginal reserve or mission, the more likely a person was to vote “no”.

That the referendum was, in the language of the West Australian, “double-barrelled” – paired with another, defeated, proposal to expand membership in the House of Representatives – does not seem to have affected the result. Even hard-right Democratic Labor Party Senator Vince Gair’s “No More Politicians Committee” advocated for a “yes” vote on “Aboriginal rights”. Left and right understood, if for sharply differing reasons, that formal discrimination needed to end.

Centre of Democracy

After the referendum

Today’s “no” campaign’s key talking point, that the Voice “lacks detail”, was made in 1967, but failed to sway many voters. A writer for the Bulletin magazine commented that while the West Australian was

right when it says there should be a policy […] the time for it is after the referendum.

What mattered wasn’t the specifics, but that policy could be developed at all.

The referendum’s aftermath also illuminates another point of difference between then and now: a lack of Indigenous opposition. Indigenous scholar Larissa Behrendt argues that an “unintended consequence” of the 1967 referendum, and the hopes it raised and subsequently dashed for many Indigenous peoples, was a “more radical rights movement” led by those “disillusioned by the lack of changes that followed”. The Commonwealth was slow to use its new powers, and reticent to override powerful premiers like Queensland’s Joh Bjelke-Petersen.

The land rights and sovereignty movements of today have their origins in this moment of radicalisation. The Referendum Council, whose 2017 Uluru Statement from the Heart reads “in 1967, we were counted, [now] we seek to be heard”, represent the unifying spirit of that earlier referendum. Indigenous critics of the Voice such as Lidia Thorpe and Gary Foley, on the other hand, inherit the radical tradition it inadvertently birthed. In Foley’s words, a Voice to Parliament would be akin to putting “lipstick on a pig”.

Does all this mean the vote will fall differently in 2023? Something Voice advocates have in their favour is that “no” supporters, while loud, appear to be in a minority. State, territory and federal leaders have unanimously pledged to support the “yes” case, leaving the federal opposition isolated, while 80% of Indigenous peoples support it.

One thing though is certain. If the 2023 referendum fails, it will at least in part be due to the shortcomings and spoiled hopes of 1967.