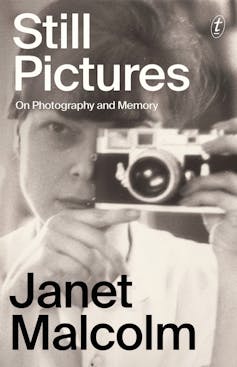

Janet Malcolm, who died in 2021 at the age of 86, left her readers this “memoir”, Still Pictures, an apt and fascinating coda to a celebrated and provocative life’s work.

As a young girl, Malcolm fled Nazism with her Czech-Jewish family on one of the last boats to sail for America. Her father was a psychiatrist, her mother a lawyer, and her work is filled with the kind of attention to people, language and the “truth” that a child might inherit from such professionals, with their specific personal history.

Malcolm’s writing is sui generis. During her 58-year relationship with the New Yorker and over the course of 13 books, she covered psychoanalysis, literature, photography, art, archives and – notoriously – journalism and biography. Her huge subjects – life and truth, their representations in art and in person – were accessed via her attention to the minutest details of a subject’s dress or gesture, a slip of the tongue, and her persistent revisiting of contradictions.

Review: Still Pictures: On Photography and Memory – Janet Malcolm (Text Publishing).

Malcolm’s shifting examination of her own premises, and her awareness of the poses and self-deceptions involved in our dealings with one another, led her works of literary journalism and biography to become commentaries on the forms themselves. The Silent Woman, a study of the “afterlives” of Sylvia Plath, and The Journalist and the Murderer, on the ethics of journalism, are famous examples.

To read a “memoir” from Malcolm, then, is to enter a realm where the very idea of memoir will be treated with mistrust.

Resistant to autobiography’s false claims and its “passion for the tedious”, Still Pictures uses photographs as imperfect and contradictory aide-memoirs. The result is Malcolmesque: fragmentary, restless and extraordinarily vivid.

I don’t think of the child as me

Still Pictures opens with a photograph of Malcolm as an impish toddler, which she uses to access her biography. But she resists the urge to use archives as evidence that substantiates memory. Disavowing connection with this lovely girl, she writes:

I don’t think of the child as me. No feeling of identification stirs as I look at her round face and thin arms and her incongruously assertive pose.

Real memory begins offstage, with a procession of girls in white dresses scattering rose petals. Wanting to join them, little Janet is given peony petals by a kind aunt, but she knows these are inferior, and the flavour of disappointment lingers across a lifetime. “I have carried this memory around with me all my life,” Malcolm writes, “but never looked at it very hard.”

But then she does. What follows is an analysis of her disappointment according to the relative merits – aesthetic, sensory, culturally bestowed – of rose and peony petals. Partial but illuminative self-knowledge is achieved via oblique enquiry. Malcolm at last begins to identify with her childhood self.

Along the way, the writing “I” invites you to question the nature of the self and its means of access to its own story.

Remembering Janet Malcolm: her intellectual courage shaped journalism, biographies and Helen Garner

The Pose

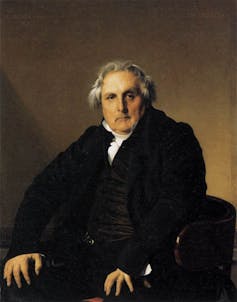

The photograph that opens out this enquiry does not stand alone. Incongruously, it appears alongside a portrait by Ingres of Louis-François Bertin, a French journalist of the 19th century: “a powerfully bulky man in his sixties […] who sits with both hands assertively planted on his thighs as he engages the viewer with a look of determination touched with irony”.

Public domain

Ingres, so the story goes, despaired of creating a successful representation of his subject, until he spied Bertin in public, sitting in “The Pose”.

The echoed pose brings the two images together. The young Janet appears to be copying him. But what both subjects are doing, observes Malcolm, is unconsciously drawing on “the repertoire of stereotypical poses with which nature has endowed all creatures, and which we tend to notice less in our own species than we do in, say, cats and squirrels and marmosets”.

Malcolm employs ways of seeing and reading that bring to light the dynamic between individual and group that guides our actions and gives them meaning. She makes them endlessly open to interpretation by those with a watchful eye and the instruments to decode their messages.

Meaningful gestures

Early in Still Pictures, Malcolm approaches memories of her mother, Hanka, via a picture of Hanka as a girl, with her sister Jiřina, and their mother Klara. In the photograph, Hanka is pushing her palm into Klara’s thigh.

As in the story of the pose and the memory of scattering petals, Malcolm interprets the gesture, “of mushing or squishing something”, through the connecting portals of memory. In her first language, Czech, the gesture, known as patlat, becomes upatlaný, or food that has been “over-meddled with”. It is a gesture she knows straight away. She recalls her mother performing it as a grown woman.

“I am not ready to write about my mother yet,” Malcolm states. So she broaches the subject of her mother indirectly, via her aunt’s family. The paths of memory are associative, and it is Malcolm’s uncle – Jiřina’s husband – who becomes the focus of the essay. He exposes the gradations of class between the sisters’ families.

Her own family, Malcolm realises now, were the poor relations, always visiting, never hosting, and it is another examined gesture that brings this dynamic to life, in the figure of her Uncle Paul:

I remember the deliberation with which he chewed his food, the assurance and self-confidence the working of his jaws seemed to express.

The image is superseded by the revelation that Malcolm’s family considered themselves, with their interest in art and literature, to be “vastly superior” to her aunt’s, for whom money and business were central.

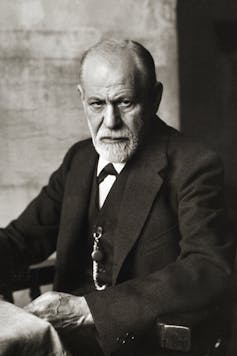

George Nikitin/AP

But wait a minute

The essay is characteristic of her method. Malcolm begins with an image, then follows the nudges and connections of memory. She lingers on details that conjure a slice of a world in its interpersonal and social dynamics, before reversing, changing tack, advancing in a new direction.

She employs the bait-and-switch technique that is a central feature of her writing, and perhaps the key to how her writing always becomes about writing – its forms, methods and assumptions. Helen Garner, a great admirer, describes the way Malcolm always pushes beyond first readings, “undercutting the certainty she has just reasoned you into accepting”.

Malcolm wonders whether we can ever “write about our parents without perpetrating a fraud”. She undermines her own enterprise before tugging you further into it. Employing a metaphor, she asks whether “the lock on the bedroom door” protects our parents from scrutiny. “But wait a minute,” she says – then picks apart the metaphor and its supposed aptness.

That move, the swiping away of assuredness, occurs continually. It creates a compelling narrative quality. What more is there to know about this? What has been missed?

Tourists in our own reality: Susan Sontag’s Photography at 50

‘Old Not Good Photos’

Malcolm was an accomplished photographer, but bad photographs – she discusses one she finds in a box labelled “Old Not Good Photos” – can yield particular rewards.

In an essay titled “Lovesick”, she compares photographs to dreams. Some are memorable, asking for interpretation.

However, as psychoanalysis has taught us, it is the least prepossessing dreams […] that sometimes bear the most important messages from the inner life. So, too, some of the drab little photographs, if stared at long enough, begin to speak to us.

Public domain

So begins an interwoven account of the habits of love in youth, adolescent reading, and an explanation of Freud’s theory of transference.

The theory contains a key to Malcolm’s methods. Transference, for Freud, described the ways in which we see each other imperfectly, “through a haze of associations with early family figures”, who play out the same old dramas. The psychoanalyst reveals what is unnoticed and proposes “an alternative script”.

In reading photographs, people and memories, Malcolm is ever alert to what goes unremarked. She opens up the possibilities we miss the first time around.

In Still Pictures, she covers a range of compelling subjects. The topics include, among many others, her parents, the delineations of class via humour and, amazingly, the story of how she took speech lessons to defend herself in court.

What we learn, as Malcolm guides us into her memories via the clues and opacities of photographs and their associated memories, is that nothing is ever finished. There is always the possibility of new meaning if we take another look.

In an Afterword, Malcolm’s daughter Anne tells us that Still Pictures was supposed to have one last chapter on Malcolm’s “lifelong interest in taking pictures”. There is no use trying to second-guess what it might have covered. As Anne observes of her mother, “the unlooked-for and idiosyncratic was her stock-in-trade”.

As much as we might feel the loss of this chapter, the knowledge of its existence as a glimmer in Malcolm’s mind is a gift. Her great and enduring interest in her subjects – “the intense pleasure she gets from looking and thinking,” as Garner describes it – makes her work come alive in the inner world of the reader. It is gratifying to learn that, right to the end, the quality of attention that so enlivened the world, for her and for us, remained undiminished.