Chileans recently voted to reject a proposed new constitution which critics said was even more authoritarian and conservative than the 1980 dictatorship-era constitution it sought to replace.

Most notably, the rejected changes sought to strengthen property rights and uphold free-market principles. Roughly 56 per cent of voters rejected the new constitution while around 44 per cent were in favour. Debates about the constitution highlight the political challenges that have plagued Chile since the violent days of the military junta.

Hosted in Santiago, the 2023 Pan and Parapan American Games, were seen as an opportunity to signal a new Chile. For Toronto-born Olympian Melissa Humaña-Paredes, daughter of Chilean political refugees, entering the Estadio Nacional (National Stadium) as a flag-bearer for the Canadian team, conjured up simultaneous feelings of pride, and the images of the atrocities from 50 years ago.

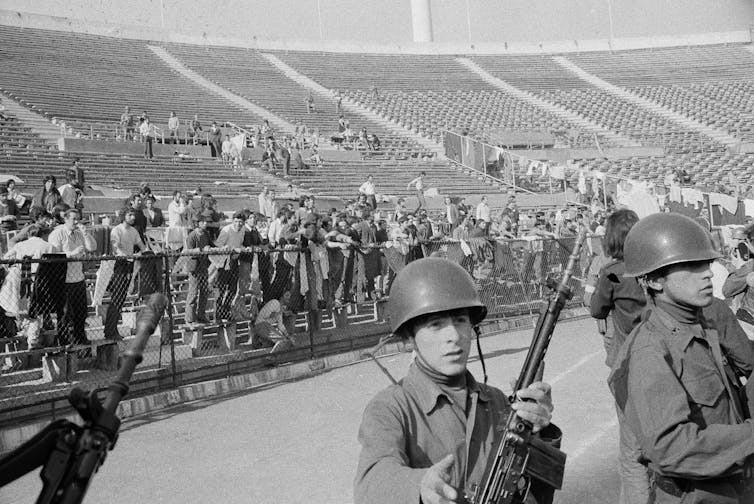

Under the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet which ruled Chile from 1970 to 1990, many sport stadiums, especially the Estadio Nacional, were used as open-air prisons, where many Chileans were tortured and killed.

Athlete activism in 1970s Chile

(AP Photo)

On Sept. 11, 1973, a coup backed by the United States overthrew the democratically-elected government of Chilean President Salvador Allende. Allende was the first Marxist president in Latin America and leader of the Unidad Popular (Popular Unity) coalition. He earned a “mythical status” among leftist political groups globally as a renowned socialist elected in the midst of the Cold War.

The defeat of Chilean democracy had devastating effects on the Chilean people. The violence of Pinochet’s reign was documented by the National Commission on Political Imprisonment and Torture. In 2011, the Commission presented a final report recognizing a total of 40,018 victims, 3,065 of them dead or missing.

Melissa’s father, sport sociologist and professor, Hernán Humaña a co-author of this article, recounts his own experiences as a Chilean national volleyball player during that time in his book Playing Under the Gun: An Athlete’s Tale of Survival in 1970s Chile.

Standing in line on the [volleyball] court, looking at the flag, and singing the anthem had turned into a painful routine for me. I felt the pain viscerally — not just in my heart. Observing spectators in the stands, also struggling during the anthem, made for an interesting study of people’s political alliances. Those supporting the military sang their lungs out, whereas those opposed either didn’t sing at all or selected only one part of the anthem, the one about “granting asylum to those persecuted.” What irony! Standing there singing, in full view of everyone, I was always aware that any departure from the norm could be dangerous for me, as the military and their supporters were humourless and would punish and persecute for such unpatriotic conduct.

Sergio Tormen Méndez and Luis Guajardo Zamorano were two athletes, less fortunate in the military junta, forcibly disappeared 10-months after the coup d’etat.

Méndez and Zamorano were two elite cyclists and friends committed to fighting the military dictatorship. On the morning of July 20, 1974, DINA, the feared secret police, kidnapped the two men along with national cycling coach, Andres Moraga, and 14-year-old Peter, Méndez’s younger brother. In subsequent days, Moraga and Peter were released with a message: Sergio and Luis are in big trouble. Numerous survivors recount seeing the two in various torture centres, yet, the details of their disappearance remains a dark secret, and their bodies have yet to be found.

(AP Photo, File)

The tireless efforts of many groups, principally the Association of Relatives of the Detained-Disappeared (Agrupación de Familiares de Detenidos Desaparecidos), have attempted to break pacts of silence amongst those responsible for human rights violations, and authorities, especially members of the armed forces, have consistently impeded efforts to pursue justice.

Efforts are further complicated by a 1978 amnesty law that pardoned perpetrators and accomplices of all offenses committed between Sept. 11, 1973 and March 10, 1978.

Since the return to democracy in 1990, only 307 previously missing victims have been identified, and Chilean courts have since processed 584 kidnapping cases, 169 murders, and 85 illegal burials under the dictatorship.

Finally, in August 2023, president Gabriel Boric’s government initiated a plan to determine the circumstances of forced disappearances and offer reparations and assurances to the families of victims.

Mythical miracles

The history of brutal violence counters the sanitized myths about a Chilean miracle popularized by people like economist Milton Friedman, who called it Latin America’s “best economic success story.”

In 2019, the attempted framing of the “miracle of Chile” could no longer be maintained. Two years after Chile was announced as host of the 2023 Pan/Parapan American Games, civic unrest erupted after the government announced an increase in transit fares. Mass demonstrations were led by students who jumped turnstiles and held open gates for people to avoid fares.

With some of the highest levels of inequality among 30 of the wealthiest nations in the world, and public officials marred by corruption scandals, Chileans were reacting to 30 years of free-market neoliberal failure.

More than a million people, from the poorest to those from upper middle-class neighbourhoods, took to the streets. Militarized police and armed forces brutally repressed demonstrations, as protesters chanted “It’s not about 30 pesos, it’s about 30 years.”

In a matter of weeks, at least 26 people were killed, 113 people were tortured, and 24 cases of sexual violence were committed by the police and army.

In response to protests, the political establishment agreed to redraft the 1980 constitution, ratified amid the bloodshed of Pinochet, and Boric was elected in December 2021 with a progressive agenda.

His minority government has struggled to implement significant changes. The first attempt to pass a progressive constitution — which included a host of rights and guarantees — was rejected in 2022.

(AP Photo/Andres Poblete)

Roughly 80 per cent of Chile’s wealth remains concentrated within the top 10 per cent, and almost 50 per cent of the total national wealth belongs to the top one per cent.

The entrance of the Estadio Nacional reads “A people without memory is a people without future” and serves as a stark reminder that memories, especially those bearing the weight of state repression in stadiums celebrated now, remain living.

The Pan and Parapan American Games and constitutional debates, while ostensibly thought to represent a new Chile, temporarily obscured histories, still repeating.

This article was also co-authored by Chilean filmmaker Hernán Morris, and Melissa Humaña-Paredes, a 2020 Tokyo Olympian.