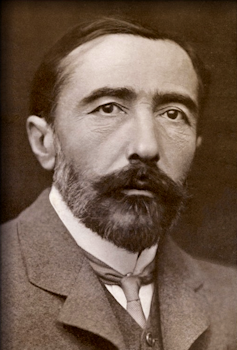

Joseph Conrad (1857-1924), the famous Polish-born author of Heart of Darkness, Lord Jim and The Secret Agent, among many other novels and short stories, is not a writer usually associated with Australia. Yet lying just off the banks of the River Derwent near Hobart there remains a haunting reminder of his presence – the partially submerged wreck of the Otago, a sailing ship he once captained when he was a roaming seafarer serving in the British merchant navy.

As a mariner, Conrad visited Australia numerous times (though, ironically, not Tasmania). The Otago, as with other ships on which he served, became the subject of many of the works he wrote in England when his sailing career ended.

A fictionalised version of Conrad, the man and the writer, forms half of Gail Jones’s new novel One Another. Significantly, Jones wrote the novel in Hobart, while taking up a writing fellowship at the University of Tasmania.

The Otago wreck is a pivotal image in the book, providing a symbolic meeting-space between the novel’s two main characters and marking a place where the past intrudes, in a bodily way, into the present.

How Conrad’s imperial horror story Heart of Darkness resonates with our globalised times

A tale of two lives

One Another interleaves the life of the celebrated writer (born Jósef Teodor Konrad Korseniowski) with that of Helen Ross, a young Australian postgraduate student of literature, who is writing her PhD thesis at Cambridge University on “Cryptomodernism and Empire” in the works of Joseph Conrad.

The narrative moves between them, reconstructing fragments of Conrad’s life and works, while narrating Helen’s attempts to write her thesis in the middle of her increasingly toxic relationship with Justin, a psychologically damaged fellow Australian.

Although these two lives are separated by time and distance, the narrative gradually and non-chronologically reveals parallels and crossings between them. The motif of journeying and outsider status is shared by both.

The orphaned Joseph is helped by his Uncle Tadeusz to leave Poland on the death of his father. He embarks on his peripatetic life, first in the French and then the British merchant navy. Later, he becomes a British subject.

Helen leaves what she sees as the constriction of Hobart to study in England, the colonial centre, in 1992. Although the text only occasionally draws attention to specific dates, the year is significant. While overseas, Helen hears of the Australian High Court’s Mabo decision, something that she recognises as “momentous”.

Heike Steinweg/Text Publishing

This underlines another common thread between the two characters: their awareness of the violence of colonialism. Each has been complicit, however tangentially, in imperial and colonial practices. Conrad witnessed the “historical cruelty” in the Belgian Congo in his role as a steamboat captain on the Congo River. Helen is a settler-colonial Australian from Tasmania, a site of violent dispossession of its Indigenous peoples.

As dislocated “foreigners” in Britain, Joseph and Helen both experience British culture as unfriendly. Joseph never loses his Eastern European accent and is self-conscious about his “broken English”; Helen’s Australian accent is regarded as “uncouth”.

Both characters are writers, and both lose a crucial manuscript – a traumatic loss that has apparently afflicted a number of other authors listed in the text. Joseph leaves the only copy of his first book, Almayer’s Folly, in a café in Berlin’s Friedrichstrasse train station; Helen leaves her thesis on a train.

In J.M. Coetzee’s latest story collection, questions of the soul become urgent as the body becomes frail

Reading as encounter

Helen’s “profound attachment” to Conrad has its childhood beginning when her father takes her on an unexpected road trip to show her the wreck of the Otago. But Helen does not attribute her interest in the writer to this sighting of the sunken ship. It is not an “epiphanic moment” or a “neat or mythic beginning”. Rather, as Jones writes: “What began was a kind of dreaming towards this emptied body, the boat.”

Helen’s absorption of Conrad’s life and work is indicated towards the end of the novel when she mirrors his language of the sea, alluding to a dream she has had as

the dark shipwreck that she has been caught in. No shape here: just her own mind tossed and unsettled.

This oceanic language of global and personal flow is a feature of the novel. In less skilful hands, it could become somewhat predictable, but Jones’s poetic way with words and imagery keeps it fresh and relevant.

To read a Gail Jones novel is to become absorbed in narrative patterns of looping time, often cinematic imagery, and interrelated literary allusions. The motif of immersion is particularly apt in this novel, not only for its connection to Joseph’s ocean voyaging and the references to a number of drownings and near-drownings.

The immersive experience of reading itself is a strong thematic thread, as it is in much of Jones’ work. It is evoked as an intimate aesthetic and philosophical encounter between reader and writer, or reader and text – and is perhaps another implication of the “one another” of the title.

The novel gradually introduces the reader to the complex pasts of its two main characters and, in the case of Joseph, his literary works. One Another includes some wonderfully perceptive and often intriguing short analyses of Conrad’s novels and short stories. These interpretations draw out the thematic connections between the stories of Joseph and Helen: loss, loneliness, friendship, violence.

There is one section that simply lists, in order, all the words from Heart of Darkness that have the negative prefixes “in-”, “im-” and “un-”. Other sections enumerate details of Conrad’s life and world under headings such as “Illnesses he suffers”, “The body” and “Accidents”.

These snippets can be read as extracts from the handwritten index cards that Helen has compiled for her thesis. Early on, she describes her lost manuscript as “fragments of a life intersected by literary-critical notations” – an accurate description of parts of the novel we are reading.

Steve Lovegrove/Shutterstock

Time is arrested in Gail Jones’ beautiful new novel of war and art, Salonika Burning

Creative biography

In many ways, then, One Another is a novel about the transformative potential of reading. It expresses the sense of intimate connection poetically, describing Helen’s “conjuring” of Conrad as “a flow into fiction’s otherness that welcomed and accommodated her”.

Jones has based the events in Joseph’s life on Conrad’s autobiographical writings in A Personal Record, his published letters, and numerous biographies and works of literary criticism. But the novel is an imaginative reconstruction of significant moments in Conrad’s world, not a historical study.

The genre of biofiction is one in which Jones has particular skill. Her early short-story collection Fetish Lives (1997) reimagines in fictional form the lives and deaths of famous writers and artists. In her recent novel, Salonika Burning (2022), she rewrites the World War I experiences of four real-life characters, including Australian writer Stella Miles Franklin, as a fictional thought experiment. But as she writes in the author’s note, Salonika Burning “takes many liberties and is not intended to be read as history”.

George Charles Beresford, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

In One Another, Jones is similarly inspired by historical events and people to write her own version of their interior lives – their thoughts and emotions, as well as of their bodily being.

The novel begins, for example, with Joseph’s dream of his parents, “the unquiet dead”, and ends with a moving imagining of his dying thoughts, as he “sinks as he has always wanted to sink, washed by kind waves, closed over by sway, hearing no language at all but that of the ocean”.

Unlike a conventional biography, One Another suggests that “for both Joseph and his biographers, there will always be the element of the hidden”. And as Helen comes to realise, the life of another is always only partially accessible:

Seeing in fragments. That was how she now thought of it. Seeing one’s own life, and another’s […] those forms of shaped meaning that might found the merest understanding.

This fractured vision – referenced in the text’s approximation of T.S. Eliot’s line in The Waste Land about fragments “shored against ruins” – implies a modernist sensibility, whereby fragmentation can create its own “forms of shaped meaning”.

Once again, Jones has written a richly evocative novel that warrants attention, both for its fascinating subject-matter and for its outstanding writerly qualities. One Another adds to her already impressive, diverse and highly-regarded oeuvre. Importantly, too, it is also a novel that adds to our understanding of the processes of writing and reading the lives of others – and one that situates Australian literature within a globalised world.