“Can’t move ‘em with a cold thing, like economics.”

So says the modernist, Ezra Pound, in the first section of his epic poem, The Cantos.

This is something I kept coming back to while watching Stefano Massini’s five-time Tony Award-winning play, The Lehman Trilogy.

Opening in 1844 and and closing in 2008, The Lehman Trilogy is self-consciously ambitious and epic in scope, concerning the spectacular rise and fall of one of America’s biggest financial institutions: Lehman Brothers.

It strives to explain the historical development of American capitalism in a single evening. While admirable, this cannot disguise the fact that the play is also wildly uneven, and chooses, problematically, to omit important – and commonly known – information regarding the Lehman family: their support for the Confederacy, their direct involvement in the slave trade, and the reasons behind the Global Financial Crisis, which ultimately led to the collapse of the financial institution they founded in 1850.

Anniversary of Lehman’s collapse reminds us – booms are often followed by busts

An international phenomenon

A cultural phenomenon in his native Italy, Massini is one of the 21st century’s most celebrated dramatists.

Born in Florence in 1975, Massini started his career as an assistant director to Luca Ronconi, who encouraged him to try his hand at playwrighting. He has since gone on to produce works inspired by writers and artists such as Shelley, Kafka and Van Gogh.

The Lehman Trilogy, Massini’s most famous work, has a curious compositional history. It started out as a nine-hour radio play in 2012, before being reworked as a five-hour, three-act piece of post-dramatic theatre written entirely in free verse.

Daniel Boud

The Lehman Trilogy debuted in Paris in 2013, was adapted by Massini into a 700-page novel that year, and was staged in Italy for the first time in 2015. This production featured 20 actors and was directed by Ronconi, who died while the play was still being performed.

Oscar-winning director Sam Mendes and Ben Power, associate director of the National Theatre, developed a comparably lyrical English-language adaptation in 2018, and now this version of the play is being staged in Australia.

A tighter retelling

Directed by Mendes and featuring a live soundtrack performed by pianist Cat Beveridge, this creation departs from Massini’s original in a number of important ways.

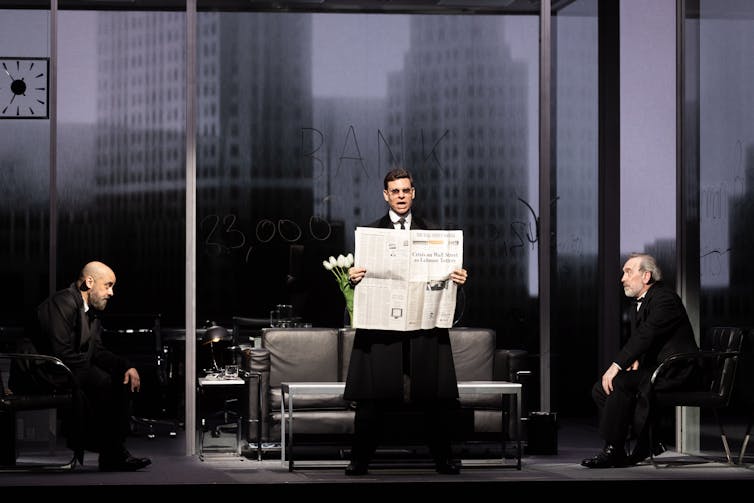

Firstly, by comparison the show is significantly shorter, clocking in at relatively trim three-and-half hours. Secondly, it has a cast of only three.

Aaron Krohn, Howard W. Overshown and Adrian Schiller play a remarkable number of male and female characters, including the three German Jewish immigrants who, in 1850, established the family business that subsequently became Lehman Brothers.

Daniel Boud

The performances they deliver are uniformly excellent and engaging. They never change costumes but transition seemlessly from character to character, delivering incredibly complex and detailed lines.

Es Devlin’s set design is equally memorable. The centre of the stage is taken up by a spinning glass box, in which the actors pace back and forth, stopping occasionally to scrawl and expunge names and numbers on the walls. The rest of the space is dominated by a panoramic digital display, which modulates as we move between different historical periods and geographical locales in the United States.

The first act opens with Henry Lehman setting foot on North American soil for the first time. After a short stint in New York City, Henry makes his way down south. He establishes himself as a goods trader in Montgomery, Alabama.

Daniel Boud

Here he is joined by his two brothers, Mayer and Emanuel. They start dealing in raw commodities: cotton, tobacco, coffee. The brothers amass a fortune. The American Civil War starts and ends. They brothers talk finance and family at great length. The money keeps on rolling in. A lot of ground gets covered in the play’s first act, yet it never feels rushed.

Unfortunately, the same can’t be said of the second and third acts.

Too much is left unsaid

Given its thematic focus and sheer duration, the play is, at times, strangely short on detail when it comes to its coverage of major economic events and financial catastrophes.

This becomes increasingly apparent as the piece progresses.

The second act focuses on the Wall Street Crash of 1929. To be sure, there are moments of genuine dramatic intensity on display in this section of the play, as when the actors describe the human damage caused in the immediate wake of the crash. Yet the pain and hardship endured during the decade-long Great Depression that came next is more or less brushed aside.

Something similar happens at the climax of the play, which wraps up without much of an exploration of the underlying reasons behind the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. This elision struck me as especially jarring and unsatisfactory, given it resulted in Lehman Brothers going bankrupt.

While there is much to praise in The Lehman Trilogy, the impression I was left with one of a missed opportunity. Still, judging by the audience’s effusive reaction, it seems clear to me that – contrary to what Ezra Pound might think – people are willing to engage with and can in fact be moved by discussions of pressing economic matters.

Surely this can only be a good thing, as we continue to lurch from one financial crisis to the next.

The Lehman Trilogy is at the Theatre Royal Sydney until March 24.

Response to past crises shames post-Lehman dithering