The United Nations counts international migrants as people of any age who live outside their country (or in some cases, territory) of birth – regardless of their motives for migrating, their length of residence or their legal status.

In addition to naturalized citizens and permanent residents, the UN’s international migrant numbers include asylum-seekers and refugees, as well as people without official residence documents. The UN also includes some people who live in a country temporarily – like some students and guest workers – but it does not include short-term visitors like tourists, nor does it typically include military forces deployed abroad.

For brevity, this report refers to international migrants simply as migrants. Occasionally, we use the term immigrants to differentiate migrants living in a destination country from emigrants who have left an origin country. Every person who is living outside of his or her country of birth is all three – a migrant, an immigrant and an emigrant.

The analysis in this report focuses on existing stocks of international migrants – all people who now live outside their birth country, no matter when they left. We do not estimate migration flows – how many people move across borders in any single year.

The world’s 10.9 million Buddhist migrants make up 4% of all international migrants, about the same as their share of the global population (4%), as of 2020.

Buddhist migrants have moved an average of 2,400 miles from their country of origin, roughly the same as Christians, Jews and the religiously unaffiliated.

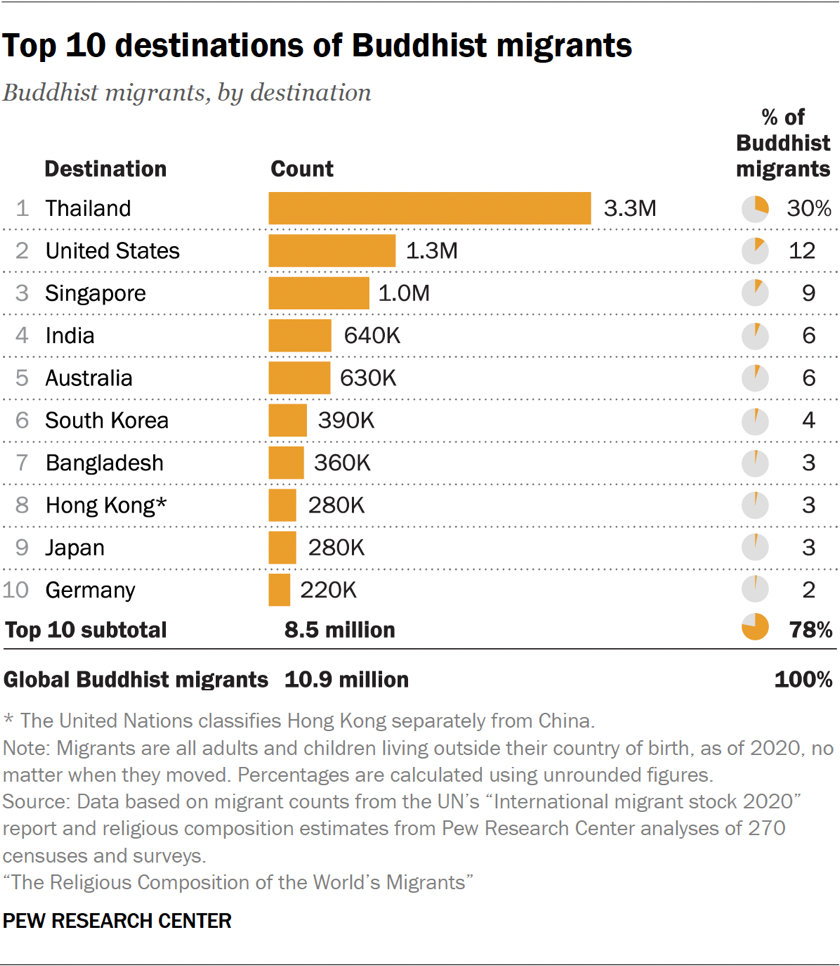

Unlike other faith groups who are more scattered across the globe, Buddhist migrants are heavily concentrated in the Asia-Pacific region (72%). Outside Asia, the most common destinations of Buddhist migrants are North America (14%) and Europe (12%). A small share of Buddhist migrants live in Latin America and the Caribbean (1%), and even fewer reside in sub-Saharan Africa or the Middle East-North Africa region.

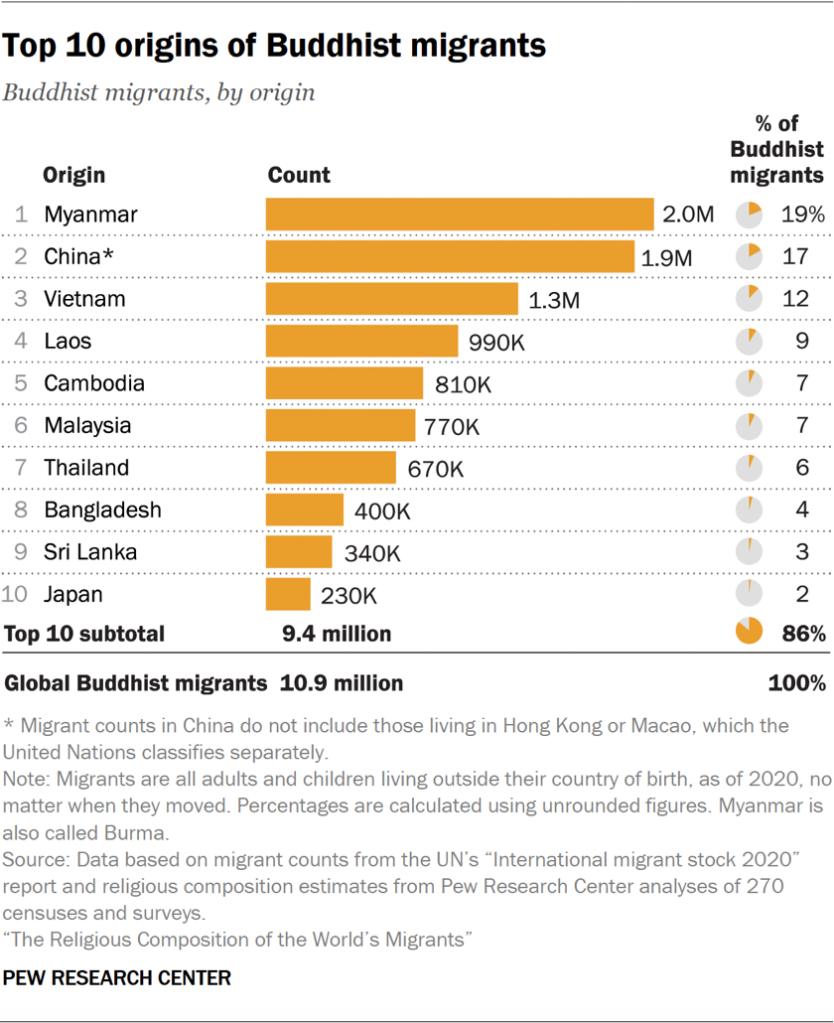

The vast majority of Buddhist migrants (96%) come from countries in Asia – the birthplace of Buddhism. Smaller shares of Buddhist migrants were born in Europe (2%), Latin America or North America (0.5% each), and the Middle East-North Africa region or sub-Saharan Africa (less than 0.5% each).

Destinations

Like migrants of other religions, Buddhists often leave their home country for wealthier economies where they can find jobs more easily. In these places, Buddhists usually make up a minority of the overall population.

Thailand is the most popular destination for Buddhist migrants, hosting 30% (3.3 million) – including many migrant workers from neighboring Myanmar (also called Burma), Laos and Cambodia. Of the 10 leading destinations for Buddhist migrants, only Thailand has a majority Buddhist population, with about 90% of adults there identifying as Buddhist.

It is also relatively common for Buddhist migrants to have moved to other stable economies in the Asia-Pacific region, including Singapore, South Korea and Hong Kong.

Singapore – Asia’s richest country on a per capita basis – is the third-most common destination for Buddhist migrants (after the U.S.), with 1.0 million. South Korea and Hong Kong are home to 390,000 and 280,000 Buddhist migrants, respectively. (Taiwan is excluded from the analysis because migration stock information for Taiwan is not available from the UN.)

The U.S. is home to an estimated 1.3 million Buddhist migrants, making it their second-most common destination. Most Buddhist migrants to the U.S. were born in Vietnam (670,000) or China (320,000).

Origins

Myanmar, where Buddhists make up 80% of the population, is the leading country of origin for Buddhist migrants. As of 2020, about 2 million Buddhists born in Myanmar live elsewhere, accounting for 19% of all Buddhist migrants.

Four other Buddhist-majority countries are the source of roughly a quarter of all the Buddhists who now live outside their country of birth: Thailand (670,000), Laos (990,000), Cambodia (810,000) and Sri Lanka (340,00o).

China – where just 4% of adults identified with Buddhism in the 2018 Chinese General Social Survey – is the second-most common country of origin for Buddhist migrants (with 1.9 million) as of 2020, due in part to the sheer size of its overall population.

Vietnam is the third-most common source of Buddhist migrants (1.3 million), followed by Laos and Cambodia.

Malaysia is another top country of origin for Buddhist migrants (770,000). Buddhists from Malaysia typically move to neighboring Singapore, where demand for foreign workers is strong and ethnic Chinese make up a majority of the general population (74%).

Most Buddhists in Malaysia belong to the country’s ethnic Chinese minority, and they have historically faced discrimination from the ethnic Malay majority, which is predominantly Muslim. While only about 7% of adults in Malaysia identify as Buddhist, Buddhists make up 37% of emigrants from there.

Country pairs

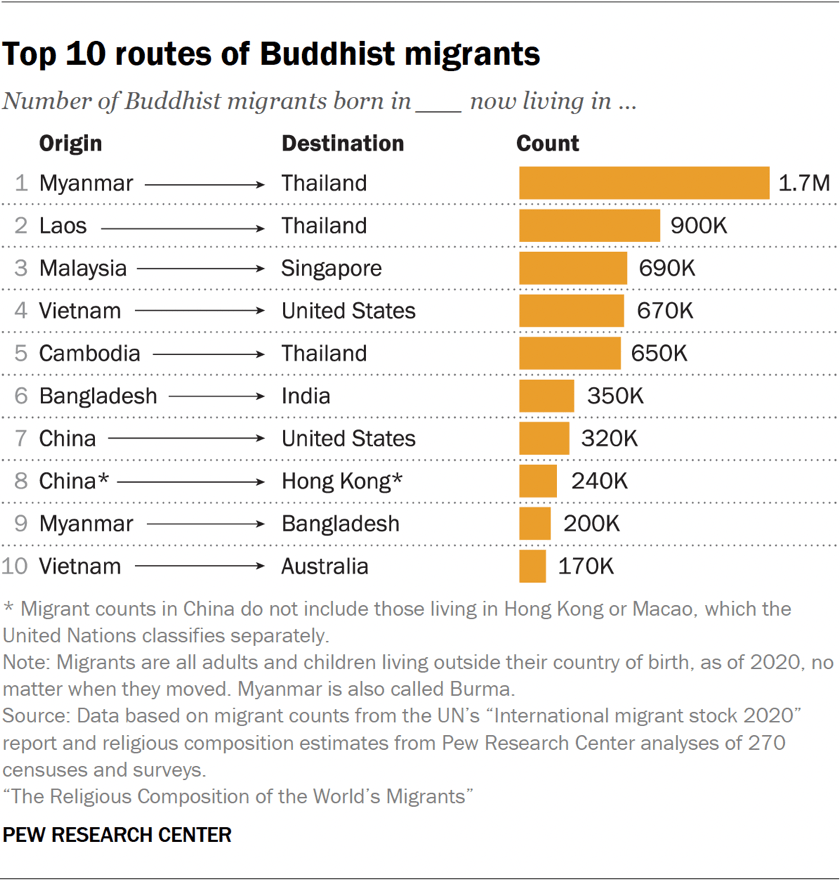

As of 2020, Buddhist migrants most commonly have moved from Myanmar to Thailand (1.7 million), and from Laos to Thailand (0.9 million).

About 690,000 Buddhists born in Malaysia now reside in Singapore, making this the third-most common path for Buddhist migrants. A similar number of Vietnamese Buddhists – who started to arrive after the end of the Vietnam War in 1975 – now live in the U.S.

These country pairs show Buddhists moving in search of economic opportunity. For instance, over 3.2 million Buddhists have migrated from Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar – each with around 20% of the population living in poverty – to Thailand, where wages are often higher and access to jobs is easier. Meanwhile, fewer than 40,000 Buddhists have left Thailand and moved to Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar.

Change since 1990

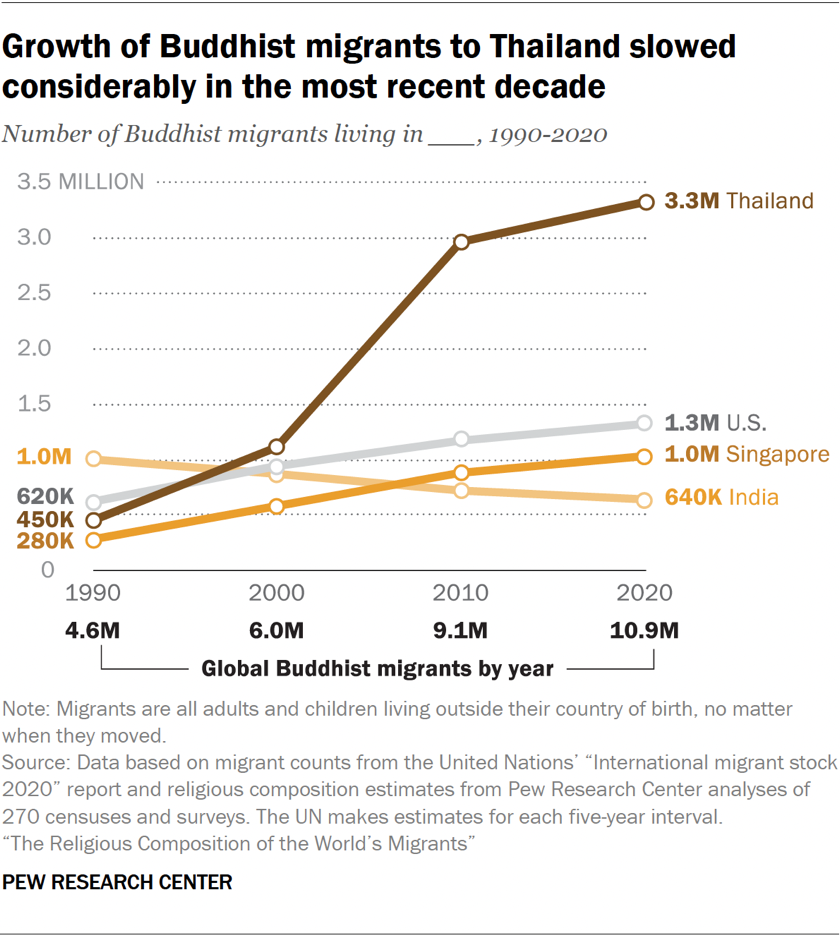

Between 1990 and 2020, the number of Buddhist migrants around the world more than doubled – from 4.6 million to 10.9 million (up 137%) – making Buddhist migrants the fastest-growing group in this analysis, ahead of Muslims (up 102%) and Christians (up 80%). But because Buddhist migrants are a very small group, they grew only slightly as a percentage of all global migrants, from 3% to 4%.

Growth in the past three decades has largely been driven by labor migration to Thailand from Cambodia, Laos and Myanmar. In the 1990s, Thailand’s economy grew rapidly, and in the early 2000s, the Thai government prioritized policies to recruit workers from these neighboring countries.

The stock of Buddhist migrants living in Thailand has surged from 450,000 in 1990 to 3.3 million in 2020 – a 630% rise. In that time, Thailand has become the top destination for Buddhist migrants, with its share of all foreign-born Buddhists rising from 10% to 30%.

Singapore – a religiously diverse and multicultural international financial center – saw its stock of Buddhist migrants jump from around 280,000 in 1990 to 1.0 million in 2020 (up 263%). The growth of the Buddhist migrant population in Singapore is on pace with that of total immigrants in the country, which rose from 0.7 million to 2.5 million. Overall migration growth in Singapore during this span is largely a result of the country’s reliance on foreign workers for economic growth. (Immigrants make up over 40% of Singapore’s total population, with Malaysia being the main source.)

The U.S., which was the second-most popular destination for Buddhists both in 1990 and in 2020, saw its Buddhist migrant population rise from 0.6 million to 1.3 million (up 112%).

While these countries experienced an influx of Buddhist migrants, India saw a considerable decline. In 1990, India had the largest number of foreign-born Buddhists – largely due to the effects of the 1947 Partition, when Buddhists from what are now Pakistan and Bangladesh settled within the new borders of India. In 1990, there were nearly 1 million Buddhist migrants living in India. By 2020, many had died, and their number had declined to 640,000 (down 35%).

Generally, the flow of Buddhist migrants has slowed in recent years. The change is particularly pronounced in Thailand. By decade, the total number of Buddhist migrants in Thailand grew by 660,000 (up 145%) from 1990 to 2000 and by an additional 1.8 million (up 166%) in the following decade. But it increased by just 360,000 (or 12%) between 2010 and 2020.