The poisoning of the unregulated drug supply, especially in Canada, is a public health crisis that deserves a high priority for the integration of evidence into policy and practice.

The drug poisoning crisis is often referred to as the opioid crisis, but it is all illicit substances, including stimulants, that are tainted with fentanyl, benzodiazepines and other dangerous ingredients, increasing the risk of harm, especially overdose.

‘Benzo-dope’ may be replacing fentanyl: Dangerous substance turning up in unregulated opioids

It is still an ongoing battle for those in positions of power to submit to the rigorous evidence supporting harm reduction, despite strategies like supervised consumption sites and the distribution of drug equipment being more than two decades old.

For example, North America’s first formal supervised consumption site, Insite, has been in operation for 20 years showcasing what its founding organization, PHS Community Services, calls a “pragmatic and humane approach to the risks of drug use.”

Thorough evaluation of harm reduction strategies has shown they can save money, save lives and promote health at an individual and population level. Furthermore, denial of access to supervised consumption is a violation of Section 7 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which protects an individual’s right to life, liberty and security of the person.

Stigma and ideology

Recently, Canada’s leader of the Opposition Pierre Poilievre had his motion to defund safer supply voted down in Parliament. His reference to a “tax-funded drug supply” as fuelling addiction rather than recovery is not supported by evidence and follows the failed prejudicial ideology of the war on drugs era.

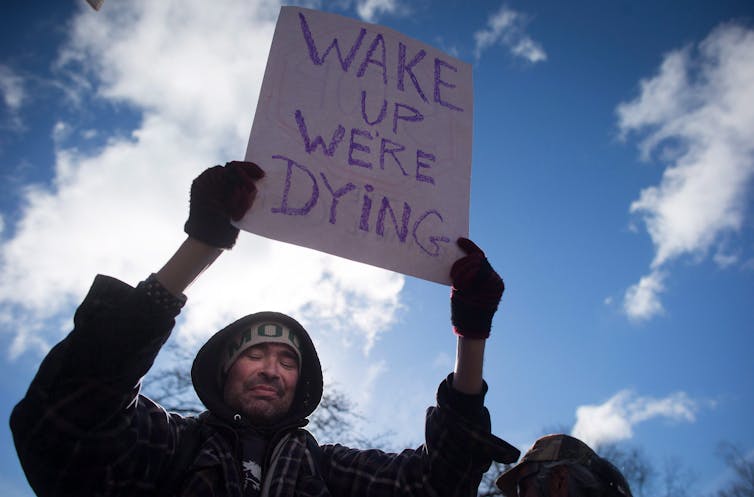

THE CANADIAN PRESS/ Patrick Doyle

Poilievre’s actions mirror the sentiments of former federal health minister Rona Ambrose, whose opinion also superseded evidence while in a position of influence. In 2013 she attempted to deny access to heroin assisted treatment (HAT) — an opioid substitution treatment using diamorphine/diacetylmorphine (medical grade heroin) — for persons with substance use disorder in Vancouver.

Ambrose publicly stated that “Our policy is to take heroin out of the hands of addicts, not to put it into their arms.”

Ambrose made this public declaration despite evidence from both Canada and Europe that showcased the efficacy of HAT in six randomized controlled trials with over 1,500 patients.

What is evidence?

What is considered evidence, especially regarding public health? From an epistemological (justified belief, as opposed to opinion) perspective, we may think evidence equals truth. However causation cannot be observed, only inferred. While evidence may be viewed as more of a confirmation, truly definitive scientific evidence is rare due to its ever-changing and evolving nature.

Evidence comes in many forms, and although it may not constitute absolute “proof,” it is reliable.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Darryl Dyck

In harm reduction, best practices are grounded in evidence that comes from several facets including peer-reviewed literature, unpublished reports or grey literature, and the experiential knowledge of persons who use drugs themselves.

The way harm reduction has progressed in Canada tells us that people who use drugs are key informants at the table as they articulate their own experience of what it is like to use substances from an unregulated supply and to navigate the health and social services system. Their voice in the conversation helps to reduce stigma, support client-centred essential services and policies, and prioritize the needs of people who use substances.

Barriers to progress

The question still remains as to why government policies across Canada, public stigma, and ignorance towards the use of substances and the people who use them, are still able to create barriers to the promotion of strategies that fight the current drug poisoning crisis.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, public health strategies were implemented at a rapid pace, but this same urgency is not translating to our community of people who use unregulated drugs. One would think that the loss of nearly 40,000 Canadians to opioid overdoses since 2016 would be impetus for not just change, but bold action.

Has government not learned its lessons about taking all aspects of evidence into consideration while also considering the urgency of action required in crisis situations? After public health failures during the 2001 SARS crisis, Justice Archie Campbell recommended in his report:

“Where there is reasonable evidence of an impending threat to public harm, it is inappropriate to require proof of causation beyond a reasonable doubt before taking steps to avert the threat…that reasonable efforts to reduce risk need not await scientific proof.”

The ultimate question that needs to be asked to those who have the power to move harm reduction forward is: If they want to be a part of ending the drug toxicity crisis, then why and for whom? Is their primary objective more votes? Or is it to value all members of our community, and not just keep people who use drugs alive, but to help them thrive?

If the goal is wanting to be a part of ending this crisis for the betterment of the persons experiencing it, then the approach must include weighing evidence from a variety of sources and triumphing over public and political ideology and stigma.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chad Hipolito

Prioritarianism, as a principle of justice, puts the focus on the population most in need, whether it be in terms of health, resources, opportunities or access. The moral and ethical values of this approach intend to maximize overall well-being for those who need it the most.

Movement forward requires collaboration that builds on existing strengths and capacities, with the guiding principle being to put the needs of the persons living this experience first. Bioethicist Anita Ho describes epistemic humility — the ability to challenge one’s preconceived and biased assumptions — as “characterized by a commitment to mutual collaboration and trust with those they serve.”

A healthy public includes us all.