As slurs go, the word “Paki” has a long, dark history in the UK. A video has emerged of the YouTuber, KSI, using the term frivolously – followed by a burst of raucous laughter by his peers.

KSI has subsequently apologised. However, this has brought back disturbing and hurtful memories for many people. As BBC broadcaster and DJ Bobby Friction, AKA Paramdeep Sehdev, put it on Twitter:

I had this racial slur thrown at me & got physical beats by racists for my entire childhood. Genuinely upset that @KSI (a guy my children love) did this & thought it was funny.

This has also highlighted the mistaken and enduring assumption that the term is a simple abbreviation of “Pakistan” and “Pakistani”. This is historically untrue.

The slur “Paki” and the racist activity denoted as “Paki-bashing”, emerged in the East End of London and spread across the country. The derogatory term was widely extended to other south Asian groups including Gujaratis, Punjabis, Kashmiris and others, regardless of religious background. Even non-south Asians were sometimes targeted with it.

That the word was used to refer to south Asians at large, as a blanket label, is in itself racist, because it ignores the multiplicity – ethnic and religious – of the many communities thus targeted. And the attendant stereotypical projections of the south Asian as “meek” and “subservient” have a long colonial history.

In his book Brick Lane 1978: The Events and Their Significance (published in 1980), the Anglican priest and Christian socialist Kenneth Leech writes:

The first reference in the press to “Paki-bashing” seems to have been on April 3 1970, when several daily papers mentioned attacks by skinheads on two Asian workers at the London Chest Hospital in Bethnal Green.

But long before these attacks, Leech notes that in 1965, the secretary of East Pakistan House, Alamgir Kabir, had claimed that there was a “growing mass hysteria against Pakistanis”.

Tom Learmonth/Alamy

Anti-south Asian racism

By the 1960s, London’s East End was home to around 8,000 Asians. Of these, 4,300 were Bengalis from East Pakistan, predominantly from the north-east region of Sylhet. Most were men who had come for economic reasons, ahead of bringing their families to the UK. Until the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence, which saw East Pakistan become an independent state, Bengalis in the UK were referred to as Pakistanis.

Enoch Powell’s inflammatory 1968 speech, Rivers of Blood, resulted in ever-increasing attacks perpetrated mostly by young people against south Asians. These included the murder, in April 1970, by a group of skinheads of Tosir Ali, a kitchen porter, at the foot of his block of flats in Bow, east London.

Powell vehemently opposed the changing demographic landscape of Britain. Bengalis from Spitalfields who were interviewed for the 1981 documentary A Safe Place to Be?, by the British director Simon Heaven, connected Powell’s speech with the racism they were experiencing. Some said they only left their homes in groups. Others told of rocks being thrown through their windows. As one man put it:

Some people thought they have a genuine right to come to this country and thought they would be welcome. But from experience, they have learned that they are the most unwelcome people, because simply the colour of their skin is not the right one.

Rising resistance

In the late 1970s, several south Asian people were murdered in the East End and beyond. In 1978, two white men and a mixed-race man killed Altab Ali on Adler Street in Tower Hamlets, near to the park which now bears his name.

While most of these racist attacks were carried out by white skinheads, some involved young West Indian men too. Geographer Shabna Begum’s research into the East End Bengali squatter movement of the 1970s notes how the East End Collinwood Gang consisted primarily of white English, but also West Indian young men “talking gleefully about their ‘Paki-bashing sprees’”.

This racism was met with resistance. Altab Ali’s murder galvanised Bengalis in East London to stand up against the National Front. The community rose up again in 1993 when eight young white men attacked a 17-year-old boy called Quddus Ali on Commercial Road in Stepney. This attempted murder left Ali left in a coma for four months. “He is permanently brain damaged,” the journalist Gary Younge reported at the time. “In the Deep South they used to call this lynching.”

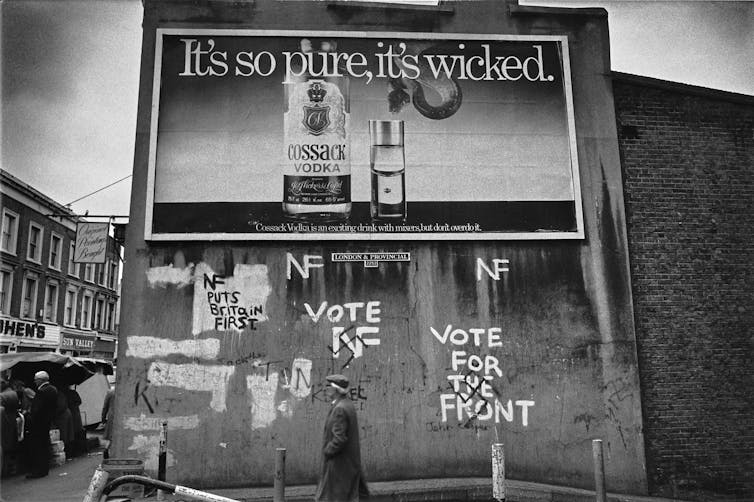

Homer Sykes/Alamy

Across the UK, Asian youth movements rose up to protest against skinheads, National Front members and other bigoted groups. The Southhall Youth Movement and wider Sikh community was prompted into action following the racist murder of an 18-year-old engineering student, Gurdip Singh Chaggar, in 1976. And a group known as the Bradford 12 formed in 1981 following racist attacks on and police harrassment of young Asian and Afro-Caribbean men. They led a five-year campaign against police racism and racist immigration laws.

Despite these resistance movements, use of the slur – and the racism that drives it – has persisted. This has been evident most recently in the legal case of professional cricketer Azeem Rafiq, who experienced racist abuse and discriminatory language at the hands of Yorkshire County Cricket Club.

Reorientating racist terms as a gimmick or for banter, as KSI and his colleagues did, not only dishonours those who have died fighting against racism. It also dilutes the violence that such racial slurs carry. When it is done on YouTube, a platform with incredible reach among young people, the effect is even worse.

As the crushing realities of racism and how it affects racially minoritised communities are made ever clearer, it is crucial to understand the history of these words. We must ensure their use is not passed down to the next generation.