Responsibility for the Earth is part of many U.S. Christians’ beliefs, but so is skepticism about climate change

Pew Research Center conducted this survey to explore the relationship between Americans’ religious beliefs and their views about the environment. For this report, we surveyed 10,156 U.S. adults from April 11-17, 2022. All respondents to the survey are part of Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education, religious affiliation and other categories. For more, see the ATP’s methodology and the methodology for this report.

The questions used in this report can be found here.

Most U.S. adults – including a solid majority of Christians and large numbers of people who identify with other religious traditions – consider the Earth sacred and believe God gave humans a duty to care for it, according to a new Pew Research Center survey.

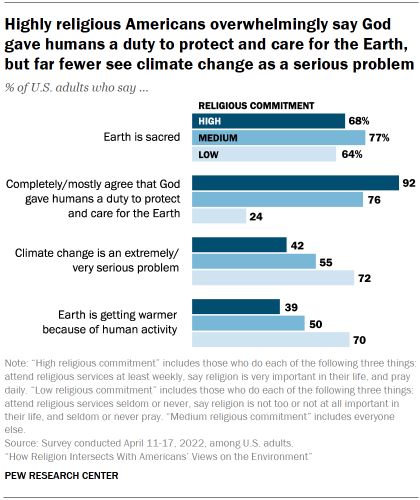

But the survey also finds that highly religious Americans (those who say they pray each day, regularly attend religious services and consider religion very important in their lives) are far less likely than other U.S. adults to express concern about warming temperatures around the globe.

The survey reveals several reasons why religious Americans tend to be less concerned about climate change. First and foremost is politics: The main driver of U.S. public opinion about the climate is political party, not religion. Highly religious Americans are more inclined than others to identify with or lean toward the Republican Party, and Republicans tend to be much less likely than Democrats to believe that human activity (such as burning fossil fuels) is warming the Earth or to consider climate change a serious problem.

Religious Americans who express little or no concern about climate change also give a variety of other explanations for their views, including that there are much bigger problems in the world today, that God is in control of the climate, and that they do not believe the climate actually is changing. In addition, many religious Americans voice concerns about the potential consequences of environmental regulations, such as a loss of individual freedoms, fewer jobs or higher energy prices.

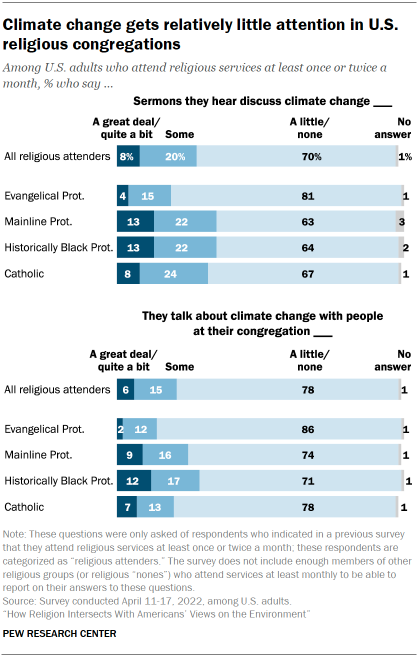

Finally, climate change does not seem to be a topic discussed much in religious congregations, either from the pulpit or in the pews. And few Americans view efforts to conserve energy and limit carbon emissions as moral issues.

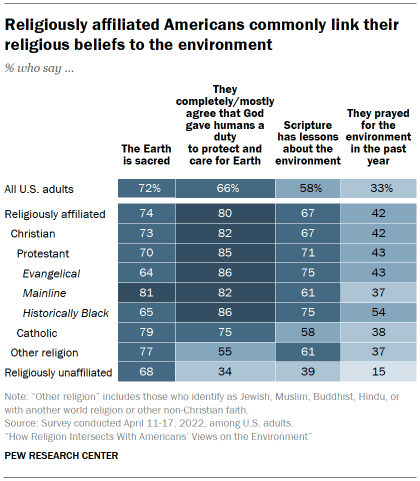

The new survey, conducted April 11-17, 2022, finds that about three-quarters of religiously affiliated Americans say the Earth is sacred. An even greater share (80%) express a sense of stewardship – completely or mostly agreeing with the idea that “God gave humans a duty to protect and care for the Earth, including the plants and animals.” Two-thirds of U.S. adults who identify with a religious group say their faith’s holy scriptures contain lessons about the environment, and about four-in-ten (42%) say they have prayed for the environment in the past year.

These views are common across a variety of religious traditions. For example, three-quarters of both evangelical Protestants and members of historically Black Protestant churches say the Bible contains lessons about the environment. Upward of eight-in-ten members of those two groups say God gave humans a duty to protect and care for the Earth. And about eight-in-ten U.S. Catholics and mainline Protestants, as well as 77% of members of non-Christian religions, say the Earth is sacred.

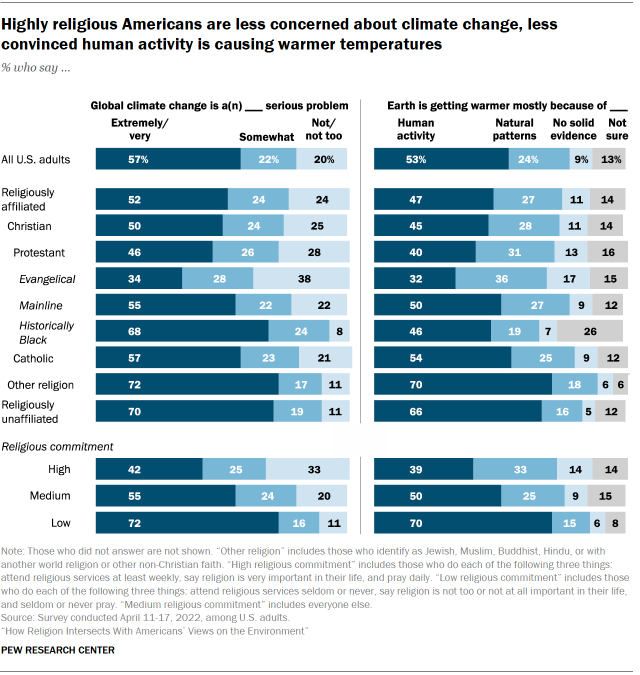

But Christians, and religiously affiliated Americans more broadly, are not as united in their views about climate change. While majorities of all the large U.S. Christian subgroups say they think global climate change is at least a somewhat serious problem, there are substantial differences in the shares who consider it an extremely or very serious problem – ranging from 68% of adults who identify with the historically Black Protestant tradition to 34% of evangelical Protestants. And half or fewer people surveyed in all major Protestant traditions say the Earth is getting warmer mostly because of human activity, including 32% of evangelicals.

On average, people who are less religious tend to be more concerned about the consequences of global warming. For example, religiously unaffiliated adults – those who describe themselves as atheists, agnostics or “nothing in particular” – are much more likely to say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem (70%) than are religiously affiliated Americans as a whole (52%). And people who have a low level of religious commitment are much more likely than those with a medium or high level of religious commitment to be concerned about climate change. Most highly religious Americans see climate change as at least a somewhat serious problem, but fewer than half (42%) say it is an extremely or very serious problem, compared with 72% of the least religious adults.

Religious “nones” and Americans with low levels of religious commitment also are far more likely than their more religious counterparts to say the Earth is getting warmer mostly because of human activity, such as burning fossil fuels. For instance, 70% of people in the low religious commitment category say the Earth is warming due to human behavior, compared with 39% of highly religious Americans. Religiously affiliated adults and those who are highly religious are more likely than those who are religiously unaffiliated or have lower levels of religious commitment to say that the Earth is getting warmer mostly due to natural patterns, or that there is no solid evidence the Earth is warming – though the latter is a less common viewpoint.

These patterns raise the question: If many religiously affiliated Americans, including most Christians, see a connection between care for the environment and their religious beliefs, then why are they less likely to be concerned about climate change than people with no religion?

There is no single, definitive answer to this question, but the new Center survey offers some clues. For one, climate change does not seem to be a major area of focus in U.S. congregations. Among all U.S. adults who say they attend religious services at least once or twice a month, just 8% say they hear a great deal or quite a bit about climate change in sermons. Another one-in-five say they hear some discussion of the topic from the pulpit, but seven-in-ten say they hear little or nothing about it. Similarly, just 6% of U.S. congregants say they talk about climate change with other people at their congregation a great deal or quite a bit.

Answers to these questions are strongly correlated with views toward climate change. For example, among all religious service attenders who say they hear at least some about the topic in sermons, 68% consider climate change an extremely or very serious problem, compared with 38% among attenders who say they hear little or nothing about it in sermons. And 61% of the former group believe the Earth is warming mostly due to human activity, versus 37% among the latter group. This does not necessarily prove that sermons are persuading people to change their views on this topic. It could also be that people seek out houses of worship where the clergy and fellow congregants generally share their views, or that they are more likely to recall sermons on topics that matter to them. But, for whatever reasons, there is a connection between religious attenders’ views on climate change and how much they remember hearing about the issue in their places of worship.

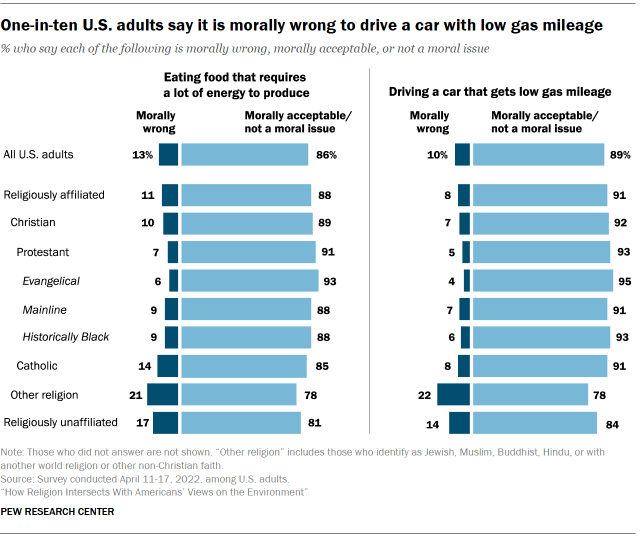

Americans, regardless of religious affiliation, also do not seem to view efforts to reduce carbon emissions in moral terms. When asked whether driving a car that gets poor gas mileage is morally wrong, morally acceptable or not a moral issue, 10% of U.S. adults – including 8% of those with a religious affiliation – say it is morally wrong. There are similar results on a question about eating food that requires a lot of energy to produce: 13% of U.S. adults say this is morally wrong.

People who identify with religions other than Christianity are modestly more likely to say these activities are morally wrong (22% and 21%, respectively), but still, most do not.

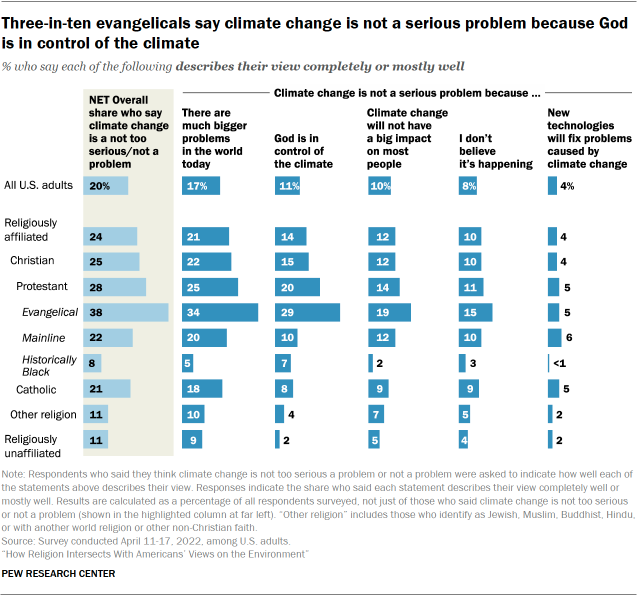

The survey also asked people who say climate change is not too serious a problem or not a problem at all a few follow-up questions designed to learn more about their views. Many people in this category say that “there are much bigger problems in the world today,” that “God is in control of the climate,” or that “climate change will not have a big impact on most people.”

For example, a third of all evangelical Protestants say climate change is not a serious problem because there are much bigger problems in the world (34%). Nearly as many say it’s not a problem because God is in control of the climate (29%). Both of these explanations are more common than the belief that climate change is not happening, which 15% of all evangelicals say is their position. (Respondents could cite more than one reason for their views. The percentages in this paragraph are based on all evangelical Protestants surveyed, not just the 38% who say climate change is not too serious a problem or not a problem.)

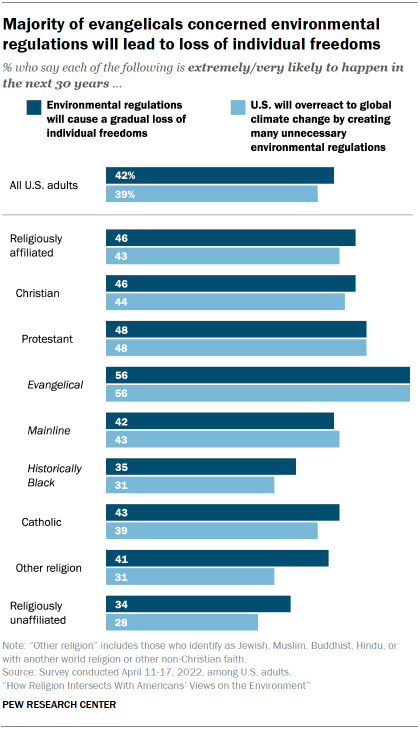

The potential impact of government regulations is another factor that may contribute to religious Americans’ views on climate change. Compared with religious “nones” (28%), more Christians (44%) – and especially evangelical Protestants (56%) – say that in the next 30 years it is extremely or very likely that the U.S. will overreact to global climate change by creating many unnecessary environmental regulations. And religiously affiliated adults also are more likely than the unaffiliated to anticipate a gradual loss of individual freedoms in the coming decades because of environmental regulations.

There are similar patterns on a question about the impact that environmental regulations could have on the economy. About half of Americans who affiliate with a religion say that stricter environmental laws and regulations cost too many jobs and hurt the economy. Evangelical Protestants are especially likely to hold this view; indeed, they are the only major U.S. religious group in which a majority take this position (66%). At the opposite end of the spectrum, two-thirds of religious “nones” say stricter environmental laws and regulations are worth the cost (68%).

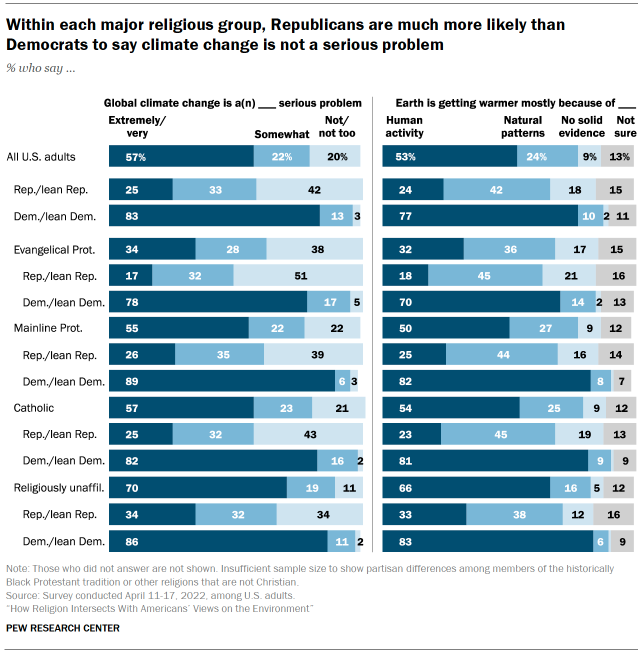

All these opinions are strongly tied to political partisanship, which emerges as a crucial factor in explaining views toward the environment and climate change. Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party are far more likely than Republicans and GOP leaners to say that global climate change is an extremely or very serious problem (83% vs. 25%) – a huge gap that underlies much of the apparent differences in views among religious groups.

For example, among evangelical Protestants who identify as Republicans or lean toward the Republican Party, just 17% say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem, only slightly lower than Republicans overall (25%). But among evangelical Protestants who identify as Democrats or lean toward the Democratic Party, 78% say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem, mirroring the 83% of all Democrats who share that view.

There is a similar pattern among religious “nones.” The vast majority of religiously unaffiliated adults who identify as Democrats or lean Democratic say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem (86%). But Republicans who do not identify with any religion (34%) look more similar to Republicans overall (25%) on this issue.

As with views about the seriousness of climate change, opinions about whether the Earth is warming and the cause of it vary by party across religious groups. Roughly three-quarters of Democrats (77%) say the Earth is getting warmer mostly because of human activity such as burning fossil fuels, three times the share of Republicans who say this (24%). And within each of the major Christian traditions, as well as among Americans who do not identify with a religion, Republicans are consistently much less likely than Democrats in the same religious group to say the Earth’s warming is mostly caused by humans.

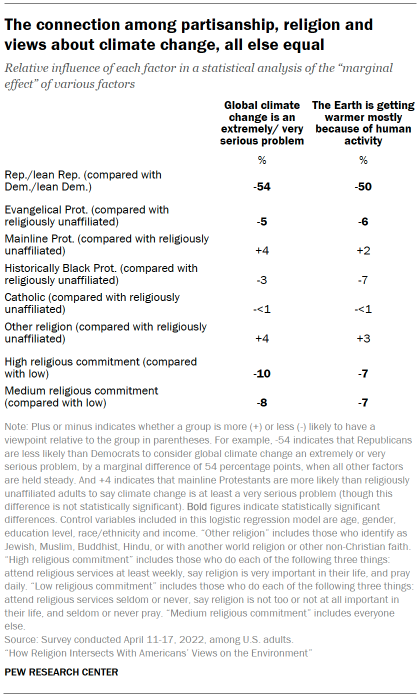

Another, more complex way to compare the impact of these factors on views toward climate change is to conduct a statistical analysis that controls for a variety of demographic factors – age, gender, education, race and ethnicity, and income – as well as political party and religion. Holding other factors (including religion) constant, what does the survey data indicate is the likelihood that a person who identifies with each of the country’s two main political parties would say that climate change is an extremely or very serious problem? And if political party and other factors are held constant, what’s the probability that someone in each of the country’s major religious groups would take the same position on climate change?

This analysis of what statisticians call “marginal effects” shows that Republicans are far less likely than Democrats – by a marginal difference of 54 percentage points – to consider climate change an extremely or very serious problem even after controlling for other factors. When political party identification and demographic characteristics are held constant, the marginal effects of religious affiliation and commitment on public opinion about climate change are much more muted – although still statistically significant in some cases. For instance, when controlling for political party, age, etc., evangelical Protestants are 5 points less likely than religiously unaffiliated respondents to say that global climate change is a serious problem, and those with high religious commitment are 10 points less likely than those with low religious commitment to hold this view.

These are among the main findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted among 10,156 adults on the Center’s American Trends Panel. The survey included Americans of many different religious backgrounds – and all are included in those described as having high, medium or low religious commitment – but this report is unable to analyze the views of non-Christian religions separately due to sample size limitations. Instead, wherever possible, the tables and charts throughout the report include an umbrella category of Americans who identify with all “other religions.” This group includes people of many faiths, such as Jews, Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus, who together make up about 6% of the U.S. adult population. Survey researchers often are reluctant to combine them into a single, umbrella category out of concern for differences in their religious beliefs, demographic characteristics and viewpoints on many issues. But on questions about the environment and climate change, the views of respondents in the “other religions” category appear to be similar enough to justify showing them together, adding a non-Christian perspective to the report.

The rest of this overview includes other key findings from the survey, including Americans’ beliefs about the “end times,” attitudes toward past and future generations, views about stewardship and dominionism, and congregations’ focus on the environment.

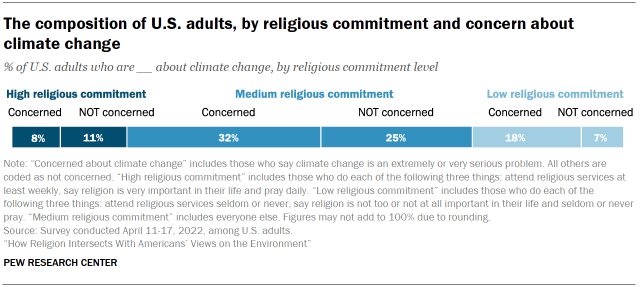

8% of all Americans are both highly religious and very concerned about climate change

While highly religious Americans are less concerned than the overall public about climate change, there is a subset of religious people who are deeply concerned about the issue. Among U.S. adults who display a high level of religious commitment, 42% say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem; this group makes up 8% of all U.S. adults. Adults who are highly religious and not as concerned about climate change make up a slightly larger share (11%).

At the other end of the spectrum, about one-in-five Americans (18%) exhibit low levels of religious commitment and also express concern about climate change. Fewer (7%) are both low in religious observance and unconcerned about climate change.

The remainder display medium levels of religious commitment, including some who are concerned about climate change (32%) and some who are not (25%).

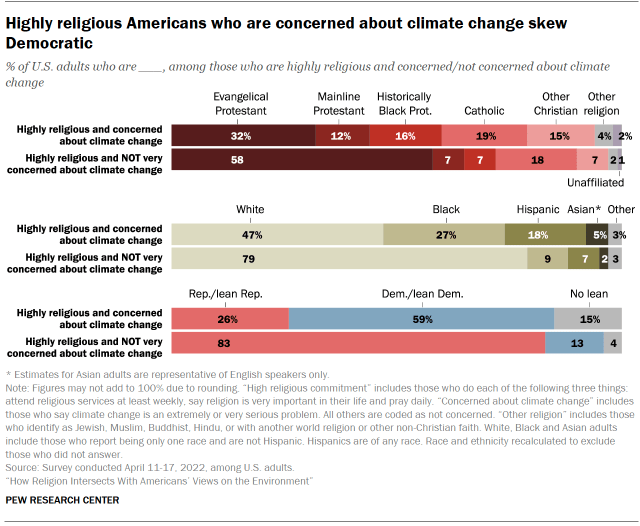

Who is both highly religious and concerned about climate change? This group consists of people who identify with many different religious traditions, including members of the evangelical Protestant tradition (32%), Catholics (19%), members of historically Black Protestant churches (16%) and mainline Protestants (12%). Another 15% identify with other Christian groups, such as Orthodox Christianity or the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and 4% identify with Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and other non-Christian religions.

By comparison, 58% of Americans who are highly religious and not very concerned about climate change belong to the evangelical Protestant tradition, while one-in-five are Catholic (18%). Smaller shares identify with other Protestant traditions, other Christian groups, and other (non-Christian) religions.

The differences among these groups illustrate, once again, the role of politics in views toward climate change. Six-in-ten of those who are both highly religious and concerned about climate change identify as Democratic or lean toward the Democratic Party (59%). The highly religious and not very concerned, on the other hand, predominantly identify with or lean toward the GOP (83%).

Highly religious people who are concerned about climate change also are racially and ethnically diverse: 47% are White, 27% are Black, 18% are Hispanic, and smaller shares are Asian (5%) or another race/multiple races (3%).

Meanwhile, the highly religious and not very concerned about climate change are predominantly White (79%), with smaller shares identifying as Black (9%), Hispanic (7%), Asian (2%), or another race or multiple races (3%). These patterns overlap with similar racial gaps between Democrats and Republicans.

Other demographic differences, including by age, between those who are highly religious and concerned about climate change compared with those who are highly religious and not concerned are relatively modest.

End-times beliefs and concern about climate change

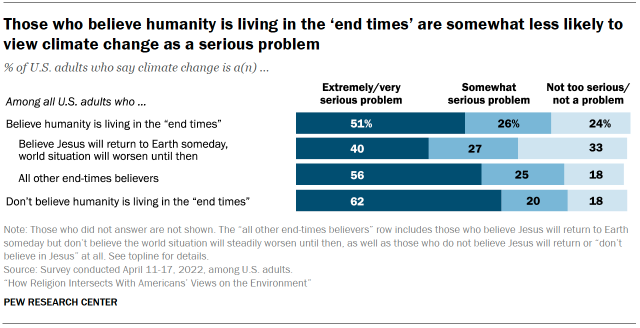

Americans’ attitudes about climate change are sometimes said to be linked to beliefs about the apocalypse or “end times.” As the theory goes, people who believe humanity is living in its last days may be less concerned about the dangers of climate change than those who do not think the world is soon coming to an end.

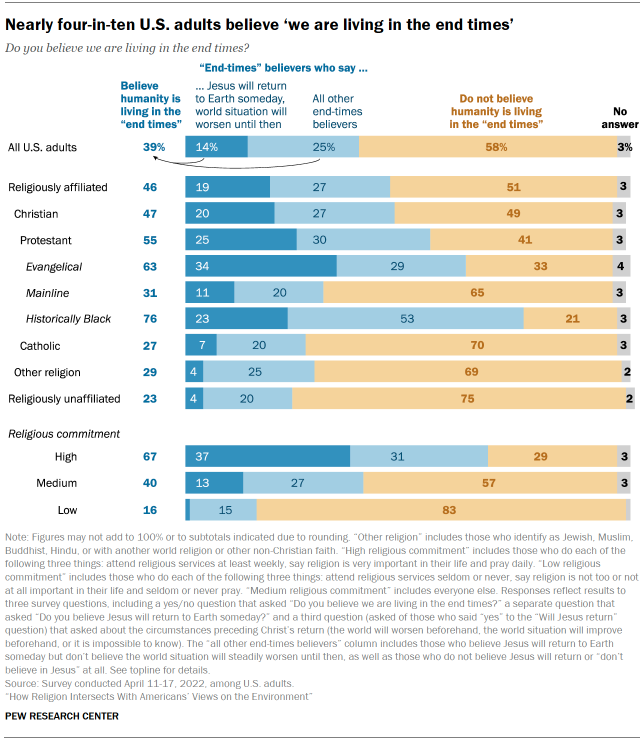

To test this proposition, the survey asked several questions about end-times beliefs. Most Americans (58%) reject the idea that humanity is in its last days, but roughly four-in-ten (39%) – including nearly half of Christians (47%) – say “yes” when asked whether they believe “we are living in the end times.” This includes 14% who express what can be thought of as a “premillennialist” point of view: They say (in follow-up questions) they believe Jesus will return to Earth someday and that the world will deteriorate until that time. A quarter of U.S. adults believe we are living in the end times but do not express this premillennialist perspective.

Roughly three-quarters of adherents of the historically Black Protestant tradition (76%) and 63% of evangelical Protestants say they believe humanity is living in the end times, as do two-thirds of all adults with high levels of religious commitment. By contrast, most Catholics, mainline Protestants, members of other (non-Christian) religions, and religiously unaffiliated Americans say “no” when asked whether the Earth is in its last days, as do majorities of those with medium and low levels of religious commitment.

The survey finds a modest relationship between end-times beliefs and concerns about climate change. Those who believe humanity is living in the end times are less likely than those who do not believe this to say they think climate change is an extremely or very serious problem (51% vs. 62%), with end-times believers who hold a premillennialist perspective expressing the lowest levels of concern about climate change (40%). Still, even in this latter group, two-thirds say climate change is at least a somewhat serious problem.

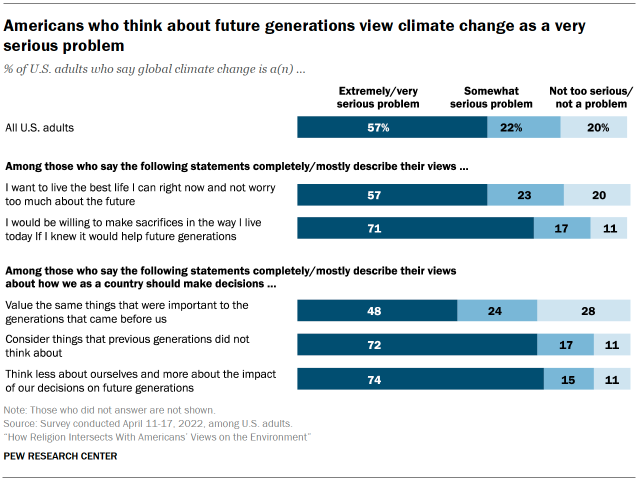

Meanwhile, U.S. adults who are more open to changing their lifestyle for future generations’ sake are more likely than others to say that climate change is a serious problem. Among Americans who say the statement “I would be willing to make sacrifices in the way I live today if I knew it would help future generations” completely or mostly describes their views, seven-in-ten say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem. Compared with this group, those who subscribe to the view that “I want to live the best life I can right now and not worry too much about the future” are less likely to say they consider climate change a serious problem (57%).

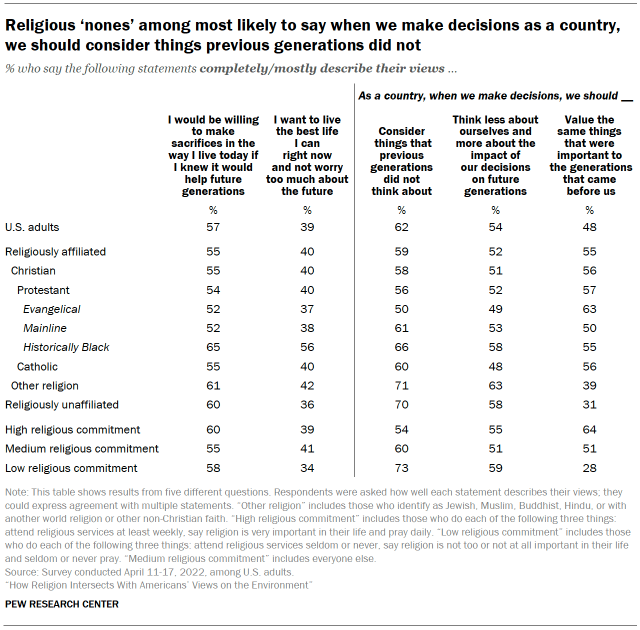

Most Americans (57%) express willingness to make sacrifices in the way they live if they knew it would help future generations, including 60% of religiously unaffiliated adults and about half of evangelical and mainline Protestants (52% each). Fewer U.S. adults (39%) say they want to live the best life they can right now and not worry too much about the future. Roughly similar shares of adults across religious groups share this view, though members of historically Black Protestant churches are the most likely to say they want to live their best lives now (56%).

Similarly, when it comes to thinking about “how we, as a country, should make decisions,” Americans who favor considering things that previous generations did not think about are more likely to express concern about climate change. Those who say we should value things that were important to previous generations are less likely to consider climate change a serious problem.

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say “we should consider things that previous generations did not think about.” Seven-in-ten religious “nones” and members of non-Christian religions say this statement completely or mostly describes their view, along with two-thirds of adults in the historically Black Protestant tradition and six-in-ten Catholics and mainline Protestants. Evangelical Protestants are the least likely to say this statement completely or mostly describes their view (50%).

Evangelical Protestants are more likely to say, on a separate question, that when we make decisions as a country, we should “value the same things that were important to the generations that came before us” (63%). Religious “nones” are the least likely to say this describes their view at least mostly (31%).

Six-in-ten religiously affiliated adults hold both stewardship and dominionist views about the environment

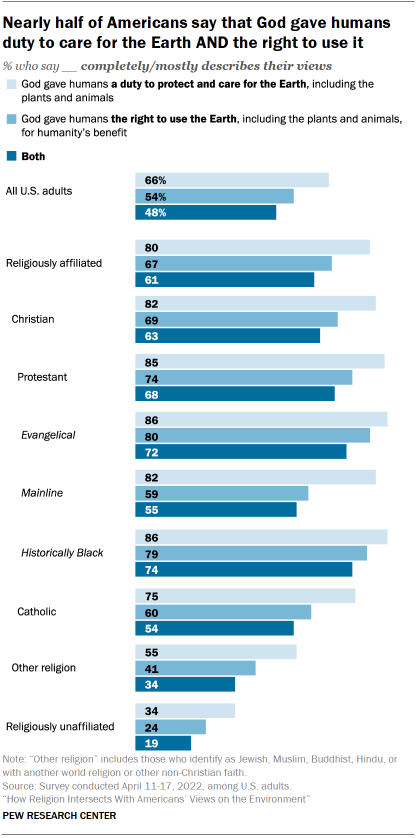

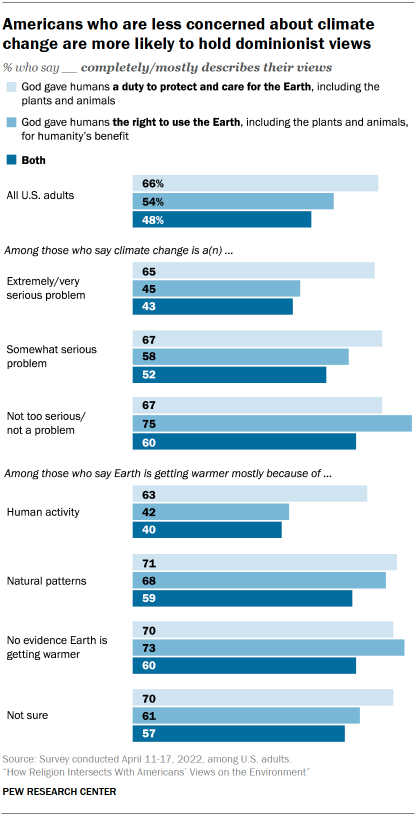

Most religiously affiliated adults say their holy scripture, such as the Bible, Torah, Quran, or other text, contains lessons about the environment. Two possible lessons that resonate with many Americans are stewardship, the idea that “God gave humans a duty to protect and care for the Earth, including the plants and animals,” and dominionism, which includes the thought that “God gave humans the right to use the Earth, including the plants and animals, for humanity’s benefit.”

Upward of half (54%) of all Americans (including two-thirds of religiously affiliated adults) say this description of dominionism mostly or entirely reflects their opinions. This is most commonly expressed by evangelical Protestants (80%) and adults who belong to the historically Black Protestant tradition (79%), while roughly six-in-ten Catholics (60%) and mainline Protestants (59%) feel this way.

Meanwhile, two-thirds of all U.S. adults – including 80% of those who identify with a religion – say the notion of stewardship, as described by the survey, completely or mostly reflects their views. This perspective is more common among Protestants (85%) than among Catholics (75%) or people who belong to other religions (55%).

All respondents who say that holy scripture has lessons about the environment were asked to describe, in their own words, what they think those lessons are. Within this group, people are far more likely to mention stewardship or people’s need to protect and care for the environment (29%) than they are to say that their religious text mentions that humans have dominion over Earth or that God put man in charge of creation (3%).

Still, many people do not see stewardship and dominionism as contradictory: Combined, nearly half of Americans say both of these perspectives completely or mostly describe their views (48%). At least seven-in-ten members of historically Black (74%) and evangelical Protestant churches (72%) say they hold views reflecting both stewardship and dominionism.

Americans who are very concerned about climate change (65%) are as likely as those who are less concerned (67%) to say the stewardship perspective completely or mostly describes their views. But when it comes to dominionism, those who are most concerned about climate change are far less likely to hold this viewpoint: 45% of those who say climate change is an extremely or very serious problem say the perspective that God gave humans the right to use the Earth for humanity’s benefit completely or mostly describes their views, compared with three-quarters of those who say climate change is not too serious or not a problem at all.

There is a similar pattern when it comes to whether the Earth is getting warmer and the reasons behind it. Majorities of Americans say God gave humans a duty to protect and care for the Earth, regardless of whether they think the Earth is getting warmer and why. But far fewer Americans who say the Earth is getting warmer mostly because of human activity also say the statement reflecting a dominionist perspective completely or mostly describes their thinking (42%). About seven-in-ten U.S. adults who say the Earth is getting warmer mostly because of “natural patterns” (68%), or who say there is no evidence that the Earth is warming (73%), take a dominionist stance.

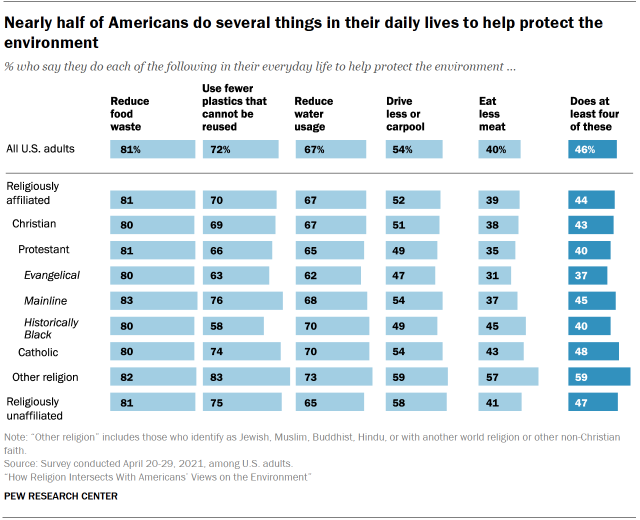

Most Americans try to do things in their daily lives to protect the environment, but the religiously affiliated are less likely to be civically involved in activities addressing climate change

Americans do a range of things in their daily lives to help protect the environment. A Center survey conducted in April 2021 found that eight-in-ten Americans (81%) say they make efforts to reduce their daily food waste to help the environment, and seven-in-ten report using fewer plastics that cannot be reused (72%). Two-thirds say they aim to reduce their daily water usage, and upward of half drive less or carpool (54%). The least popular activity of those mentioned on the survey is eating less meat to protect the environment; 40% of Americans make this effort. All told, 46% of U.S. adults say they do at least four of these five activities to help protect the environment.

These activities tend to be reported by similar shares of Americans across religious traditions and among the religiously unaffiliated, save for eating less meat. More than half of Americans (57%) who identify with non-Christian religions say they eat less meat to help the environment, compared with fewer than half of Christians and religious “nones.” Evangelicals are the least likely to say they eat less meat to help protect the environment (31%). Members of non-Christian religions also are the most likely to say they use less plastic to help the environment (83%).

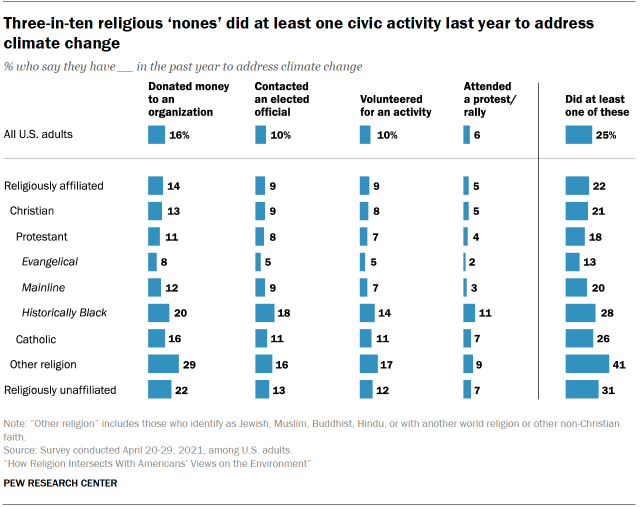

When it comes to participating in activities that help address climate change, a quarter of Americans say they have done at least one of the following activities in the past 12 months (prior to when these questions were asked in April 2021): donated money to an organization focused on addressing climate change; contacted an elected official to urge them to address climate change; volunteered for an activity focused on addressing climate change; or attended a protest or rally to show support for addressing climate change.

Religiously unaffiliated adults (31%) are more likely than those who are affiliated with a religion (22%) to report having performed any of these activities in the name of climate change, although members of non-Christian religions are most likely to have done at least one of these things (41%). There also is variance across Christian traditions, with members of the historically Black Protestant tradition (28%) more likely than evangelicals (13%) to engage in these activities.

Other findings from the new survey include:

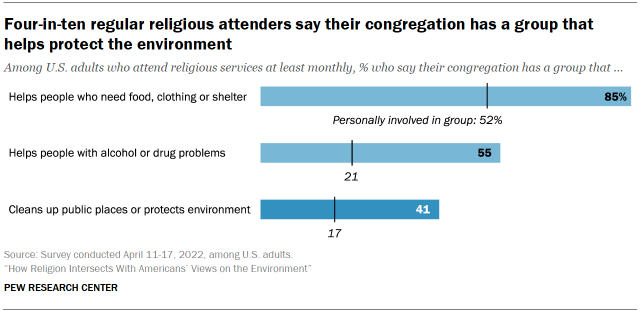

- U.S. congregations appear to be more likely to focus on other – perhaps more personal – ways of helping the community, rather than cleaning up public places or protecting the environment. Among all U.S. adults who attend religious services at least once or twice a month, a large majority (85%) say their congregation has a group that helps people who need food, clothing or shelter, and just over half (55%) say their house of worship helps people with alcohol or drug problems. Fewer (41%) say their congregation has a group dedicated to helping clean up public places or protecting the environment, and just 17% say they are personally involved in that group.

- Among U.S. adults who attend religious services at least monthly, 46% say their congregation has recycling bins, 43% say their house of worship takes steps to be more energy efficient and 8% say it uses solar power.

- Fully seven-in-ten Americans say they find meaning in nature (71%), including 38% who find a great deal of meaning from spending time outdoors. There is relatively little variation by religious affiliation on this question. For example, 74% of mainline Protestants, 71% of Catholics and religious “nones,” and 70% of evangelical Protestants say they draw meaning from nature and the outdoors. But members of historically Black Protestant churches, who are among the most concerned about climate change, are the least likely to derive at least quite a bit of meaning from spending time outside (56%).