Written testimonies from the medieval period show sexual assault being successfully reported to the authorities, despite legal, social and even family obstacles. This took place, we must remember, in a society which had next to nothing by way of forensic measures, so reporting a crime of any sort often meant that people had to be taken at their word.

Almost 30 years ago, pioneering research was carried out by medieval history professor María del Carmen Pallares into such cases in 15th century Ourense, a city in Galicia, in northwestern Spain. More recent contributions to this body of research have continued to shed light on cases that date back to the Middle Ages and beyond.

A. L-R., Author provided

To this day, taking successful action against sexual assault remains difficult. In Spain, for example, the process of implementing a law dubbed “solo sí es sí” (“only yes means yes”) has highlighted the problem of standardising offences and the “demonstrability” of sexual assault.

When tracing such crimes in thousand-year-old documents, the evidence must therefore be considered with caution, and there are various barriers to interpreting it. These can be linguistic (documents were written in Latin or older Romance languages), legal (there is, for example, no exact legal equivalent to the modern definition of rape) and representational (very few documents give specific details of crimes committed).

In spite of these limitations, I have chosen two documented cases which clearly show women reporting and taking action against collective or individual sexual assault by men.

Celanova, Galicia: a granddaughter reports her grandfather

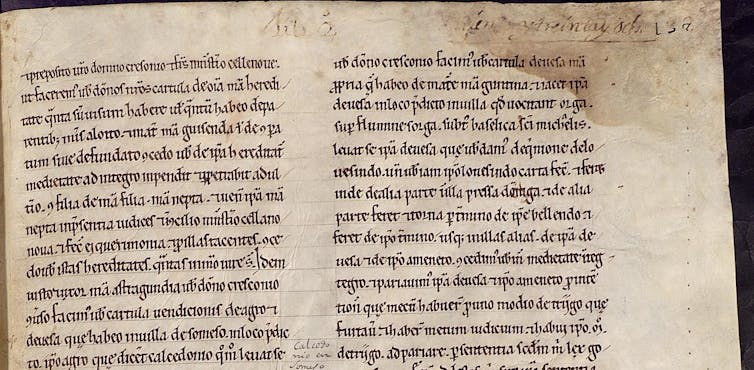

The written records, known as the cartulary, of the monastery of Celanova in Galicia are an excellent source of information on early medieval society in the northwestern Iberian Peninsula. The documents it contains are mainly copies of earlier ones from the 10th or 11th centuries.

National Historical Archive, Madrid, codex L. 986, f. 137r.

Towards the end of the 10th century, there was an account of a woman, possibly a young girl, going to the monastery to report her own grandfather for having abused her (as stated in Latin: venit ipsa mea nepta in presentia iudices in concilio). The granddaughter’s name is not known, because the document focuses on the grandfather himself, who went by the name Tusto.

In the written account he acknowledges his guilt, and explains that his granddaughter’s report (queremonia) was what brought him before the authorities. In the end, the aggressor agrees to hand over a number of family possessions as punishment for illicit relations (adulterio), which then pass into the hands of the monastery.

The account is surprisingly explicit in mentioning both the family connection and the acknowledgement of guilt. Unfortunately, we know nothing more about Tusto and his anonymous granddaughter, but we do know from this account that she had the opportunity to successfully report her aggressor despite the nature of their relationship, and that action was taken.

São Pedro do Sul, Portugal: Jimena and Juan Arias

Another explicit mention of sexual assault being reported can be found found in a document dated to almost a century after Tusto’s case.

In this case a woman, Jimena, and her mother, Ducidia, hand over a number of church goods to a powerful local magnate named Alvitu Sandizi. Jimena and Ducidia asked for his help because a man named Juan Arias had attempted to assault Jimena, or to consummate a relationship against her will (the Latin reads: volebat concubare sine mea volumtate). It seems that Alvitu was something of a well known and respected local authority, which explains why they turned to him at this moment.

The most striking element of this case is that Jimena appears in the first person (mea). She explains that the goods had been delivered as protection against Juan Arias’ unwanted advances, and to clearly record her explicit lack of consent.

The tip of the iceberg

It would, of course, be impossible to quantify the number of sexual assaults that took place over the course of centuries. However, in our doctoral thesis project, and in other publications, we have tried to compile all available recorded instances. The two listed here are the clearest examples of women reporting such crimes, but they are by no means the only ones.

These historical accounts run contrary to popular, heroic tales like Ingmar Bergman’s 1960 film The Virgin Spring, or Ridley Scott’s more recent 2021 film The Last Duel. They show that crimes such as these were reported by women who were taken at their word, and action was taken by ordinary, established justice systems.

FilmAffinity

Analysing and learning about these stories not only sets a historical precedent for the present, but also helps us to change the way we see the past. It is the responsibility of historical researchers to bring back this evidence and share it. In this way, the actions of Tusto’s granddaughter, Jimena and her mother, and countless others can contribute to a society where women are taken seriously when reporting sexual assault.