Most see their society as more divided than prior to the pandemic – and this view is especially common in the U.S.

Publics are increasingly satisfied with the way their country is dealing with the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a recent Pew Research Center survey in 19 countries. A median of 68% think their country has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak, with majorities saying this in every country surveyed except Japan. However, as the survey also highlights, most believe the pandemic has created greater divisions in their societies and exposed weaknesses in their political systems. And across these nations, partisan divisions play a key role in shaping attitudes toward the pandemic.

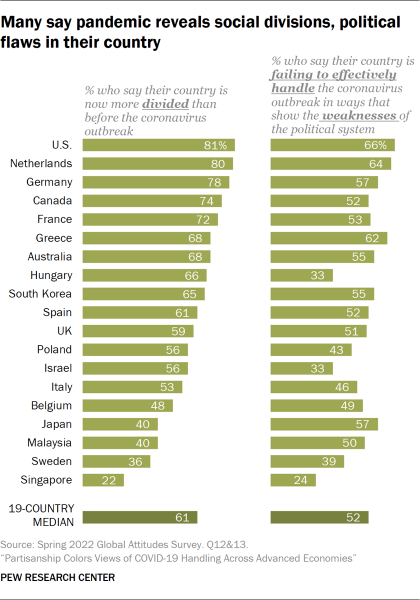

Overall, a median of 61% think their country is more divided now than it was prior to the outbreak of the pandemic, compared with a median of 32% who think their society is now more united. As was also the case in 2021, the United States has the highest share who say the country is more divided than before the pandemic, with 81% holding that view. Around three-quarters or more also see disunity in the Netherlands, Germany, Canada and France. Only in Singapore, Sweden and Malaysia do majorities feel more united than before the pandemic.

Many also believe the pandemic has revealed weaknesses in their political systems. On balance, more people say their country is failing to handle the COVID-19 outbreak in ways that show the weaknesses of their political system (a median of 52%) than see their country effectively handling the pandemic in ways that show the strengths of their system (a median of 44%). In the U.S., around two-thirds see the country struggling in ways that reveal political weakness, and a majority also feels this way in the Netherlands, Greece, Germany, Japan, Australia and South Korea. Only in Singapore, Hungary, Israel and Sweden does a majority feel the opposite – that the way their country has handled the coronavirus outbreak highlights their country’s political strengths.

All of these opinions about the COVID-19 pandemic and its effect on government and society are heavily colored by partisanship. In almost every country, supporters of the governing party are much more likely to say their government is handling the coronavirus outbreak well, to say their country is handling the pandemic effectively in ways that show the strengths of the political system and to say their country is more united compared with before the COVID-19 pandemic than people who do not support the governing party (for more on how the governing party in each country is defined, see Appendix A). In many cases, the differences are quite substantial. For example, Poles who support Law and Justice (PiS) are around twice as likely – or more – than those who do not support the governing party to say the government has done a good job (89% vs. 44%, respectively), to say the country is united (55% vs. 20%) and to believe the pandemic has illuminated the political system’s strengths (83% vs. 28%).

Views of the economy are also closely related to all of these opinions. Those who say their economy is in good shape are much more likely to approve of their government’s handling of the pandemic and to say their government’s response highlights the strengths of their political system than those who think the economy is in bad shape. People with rosy views of the economy also see the country as more united than those who have bleaker economic assessments.

The survey also asks about the relative importance of getting a coronavirus vaccine to be a good member of society. In every country, around two-thirds or more say it’s at least somewhat important to do so. But the share who says it’s very important to get the COVID vaccine in order to be a good member of society varies widely, from around four-in-ten or fewer who say this in France, South Korea, Hungary and Poland to around seven-in-ten or more who feel this way in Singapore, Sweden and Spain. And, in this case, opinion is related to on-the-ground reality: Countries with higher shares of people who report that it’s very important to get vaccinated also have higher rates of vaccination across the population.

Still, as with all other coronavirus-related attitudes explored here, the perceived importance of the vaccine is heavily partisan in nature. In every country surveyed, those who support the governing party or coalition are much more likely to say it’s very important to be vaccinated than those who do not support the ruling party. In Canada, for example, 80% of those who support the governing Liberal Party think getting a vaccine is very important, compared with 51% of those who do not identify as Liberal partisans.

In many countries, those on the ideological left are significantly more likely than those on the right to say getting a coronavirus vaccine is very important. However, this pattern is reversed in Hungary, Poland and France.

These are among the major findings of a new Pew Research Center survey, conducted from Feb. 14 to June 3, 2022, among 24,525 adults in 19 countries. The survey also finds substantial age gaps in many countries across the four questions analyzed in this report. In most countries surveyed, adults over age 50 are much more likely than adults ages 18 to 29 to say the coronavirus outbreak has been handled well and to say that their country is effectively handling the outbreak in ways that show the strengths of the political system. In over half the surveyed countries, older people are also more likely to think their country is now more united than before the coronavirus outbreak. Finally, older adults are likelier to say that getting a coronavirus vaccine is important to being a good member of society in nearly every country surveyed.

Most look favorably upon their country’s COVID-19 response

Even as COVID-19 variants have risen and fallen and pandemic policies have ebbed and flowed, majorities in most places approve of their country’s coronavirus response: A 19-country median of 68% say their government has done a good job dealing with the pandemic, while a median of 32% say their country has done a bad job.

Positive feelings are most common in Singapore, where nearly nine-in-ten adults say the city-state has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak. Singapore abandoned its “zero COVID” policy last October, but it was largely successful at suppressing the spread of the virus prior to the development of effective vaccines.

Ratings are also very high in Sweden, where the government bucked the international consensus and refused to implement mandatory restrictions early on to reduce the spread of the virus. About eight-in-ten Swedes say their country has done a good job dealing with the coronavirus outbreak.

Opinions are least positive in Japan, where 52% say the government’s response to the coronavirus outbreak has been good and 47% say it has been bad.

In many countries, adults are now happier with their government’s COVID-19 response than they were last spring. Belgium, in particular, has seen an increase in the share who say the country has handled the coronavirus outbreak well. In 2021, half of Belgian adults thought their government had done a good job dealing with the pandemic.

Now, nearly three-quarters of Belgians (73%) rate the response positively. Ratings have also significantly improved in Spain, Japan, the U.S., France, Italy, Sweden, Germany and Canada.

In three countries, however, coronavirus response assessments have become more critical. South Korea reports a 13-point decrease in the share who say that their country has done a good job responding to the coronavirus outbreak. Opinions in Singapore are down slightly, from 97% in 2021 to 88% in 2022. Australia, which in 2020 and 2021 had near unanimous agreement that the country had done a good job dealing with COVID-19, shows a 19-point decline in the share who say that in 2022. Since the question was last asked in 2021, Australia ditched its “COVID zero” stance after frequent mass lockdowns in many state capitals and the spread of the delta variant.

Pandemic response ratings are significantly more positive among supporters of the governing party or parties than nonsupporters in every country but Malaysia. For example, 72% of supporters of German Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s three-party “traffic light coalition” say Germany’s pandemic response has been good, while only 57% of nonsupporters hold that view – a difference of 15 percentage points.

Views of COVID-19 responses are also closely tied to assessments of the current economic situation. As many countries grapple with rapid inflation, supply shocks from the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the threat of global growth slowdown, the economic recovery from the pandemic has been unsteady. Those who have positive views of the current economic situation in their country are more likely to think their country’s coronavirus response has been good in every country surveyed. This includes double-digit differences in all countries surveyed and differences of 30 points or more in 9 countries.

Though there was a strong relationship between positive assessments of a country’s handling of the pandemic and the number of virus-related deaths in that country in 2021, the same is not true in 2022. In fact, views of a country’s handling of the pandemic in 2022 are largely unrelated to the number of deaths in the country, the number of cases or the vaccination rates.

Most people say the pandemic has divided their society

Across the 19 countries surveyed, people largely feel their society is more divided now than before the coronavirus outbreak. A median of 61% feel the pandemic has divided their country, while only 32% think it has left their country more united than before. This includes majorities in 13 countries who say their country is more divided than before the pandemic.

Once again, the U.S. is the country with the highest share who say that the country is more divided than before the pandemic, with 81% holding that view. About eight-in-ten in the Netherlands and Germany also feel their respective countries have seen increased division since the coronavirus outbreak.

Singapore, Sweden and Malaysia stand out for having majorities say their country is now more united than before the pandemic. Views in Japan, Belgium and Italy are split, with some seeing increased division and others seeing increased unity.

While perceptions of pandemic-related division continue to be common in many countries, they are nonetheless also significantly down from last year in several countries. For example, 59% of Japanese adults said their country was more divided than before the pandemic, when asked in 2021 just ahead of the Tokyo Olympics. Today, only 40% in Japan say the country is more divided. Double-digit decreases in the share who say their country is more divided also appear in Belgium, Sweden, Spain and Italy.

In Canada and Australia, the opposite is true. The share of Canadians and Australians who say their country is more divided has steadily increased since the question was first asked in the summer of 2020.

Though majorities in many countries see increased social divisions, the question of the pandemic’s effect on national unity is itself divisive. One major divide is between those who support the governing party or parties in their country and those who do not. In every country but Germany and the Netherlands, those who do not support the governing party or parties are more likely to see increased division than those who support the party or parties in power. For instance, only three-in-ten Poles who support the ruling Law and Justice Party (PiS) say there has been increased division since the coronavirus outbreak; among those who do not support PiS, two-thirds say Poland is more divided.

More say COVID-19 exposed the weaknesses in their political system than the strengths

In most countries surveyed, half or more say their country is failing to effectively handle the pandemic in ways that show the weaknesses of their political system. Overall, a median of 52% across the 19 countries surveyed see their country struggling in a way that reveals their political weaknesses. While this opinion is highest in the U.S., where 66% feel that way, a majority share the sentiment in the Netherlands, Greece, Germany, Japan, Australia and South Korea.

Still, a median of 44% say the opposite – that their country is effectively handling the coronavirus outbreak in ways that show the strengths of their political system. This opinion is highest by far in Singapore, where around three-quarters hold this view, but a majority also feel this way in Hungary, Israel and Sweden.

People who support the current party or parties in power are much more likely to say their country is effectively handling the COVID-19 outbreak in ways that show the strengths of their political system than those who do not support those currently in office. In some countries, these differences are massive. For example, in Greece, 79% of those who support New Democracy (ND), the party currently in power, think that their country’s effective handling of COVID-19 highlights the strengths of the Greek political system, while only 20% of those who do not support ND feel the same.

In Poland, too, the difference between Law and Justice supporters and others is 55 percentage points and in France, En Marche supporters differ from others by 45 points.

While there is also a partisan gap in the U.S., the gap is somewhat smaller: 42% of Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party think how the U.S. has handled the pandemic demonstrates the strengths of the political system, compared with 19% of Republicans and GOP leaners. Notably, the U.S. is one of the only countries where a minority of those who support the governing party think their political system appears strong on the basis of its pandemic approach.

The same is true when it comes to whether people think their country is more united or divided now than it was before the pandemic. In every country, those who think the country is now more united than it was before are more likely to say COVID-19 highlighted the strengths of their political system than those who think their country is more divided. The magnitude of these differences is often quite sizable. For example, in Australia, 73% of those who think the country is now more united say they see the strengths in their political system thanks to the pandemic, compared with 32% of those who think the country is now more divided.

In most countries surveyed, older people are more likely than younger people to say that the way their country has handled the coronavirus outbreak shows the strengths of their political system. In the United Kingdom, for example, 58% of those ages 50 and older think this, compared with 44% of those ages 30 to 49 and only 29% of those under 30.

In every country surveyed, people who think the economy is in good shape are also more likely to say their system is effectively handling the coronavirus pandemic in ways that show their political strengths than those who think the economy is in bad shape.

Most see vaccines as at least somewhat important for being a good citizen

Around two-thirds or more in every country surveyed say it’s at least somewhat important to get a coronavirus vaccine to be a good member of society. But, the share that describes it as very important varies substantially across the 19 nations, from around seven- in-ten who feel this way in Singapore, Sweden and Spain to around four-in-ten or fewer in France, South Korea, Hungary and Poland.

Across the 19 countries surveyed, there is a positive relationship between the share of the public who think it’s very important to get a vaccine to be a good member of society and the actual population that was fully or partially vaccinated at the time that fieldwork began (r=0.64).

In almost every country, those ages 50 and older are more likely to say it’s crucial to be vaccinated to be a good member of society than younger people – especially those under 30. Opinion across age groups often varies widely, too. In South Korea, for example, 54% of those 50 and older think it is very important, compared with around a third of those ages 30 to 49 and about one-in-five of younger adults.

Partisan preferences also play a strong role in whether people think vaccination is crucial to be good members of society. In every nation, those who support the party or parties who are currently governing are much more likely to say it is very important to be vaccinated than those who do not support the ruling parties. This difference is largest in the U.S., where 64% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents think vaccines are very important, compared with 20% of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents.

There are also large ideological differences in nearly every country where left-right ideology is asked. In the U.S., South Korea, Canada, Italy, Israel and Spain those who place themselves on the left are more likely to call vaccination very important for being a good citizen than those on the right; however, the opposite is true in Hungary, Poland and France. In the U.S., again, the differences between people on either side of the ideological spectrum is greater than in any other country surveyed (46 percentage points).

In some cases, right-wing populist party supporters are less likely than nonsupporters to say it is very important to get a vaccine. For instance, only 24% of Germans with a favorable view of Alternative for Germany (AfD) say vaccination is very important, while 64% of those with an unfavorable view say getting a vaccine is very important. For more information on European populist parties, see Appendix B.

CORRECTION (Oct. 31, 2022): The chart “Americans are the most ideologically divided about the importance of a COVID vaccine” and text related to ideological differences in views of the COVID-19 vaccine have been updated to correct a statistical significance labeling error for Germany and Greece. These changes did not affect the overall narrative of the analysis.