The latest labour force data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics shows employment in February increasing by 64,600, and the (seasonally adjusted) unemployment rate declining from 3.7% to 3.5%.

It’s confirmation that it’s still too early to declare that the labour market has reached a turning point, after which we can expect the rate of unemployment will rise for some time.

Employment growth has been slowing over the past year, but ups and downs from month to month make it difficult to work out how fast that is happening. Meanwhile, the rate of unemployment is stubbornly resisting moving too far from 3.5%.

Predictions have been hard

Making any predictions for the labour market since mid-2022 has been more difficult than usual.

In the first six months of 2022, employment grew by 56,600 per month, while the rate of unemployment fell from 4.2% to 3.5%. But for the next three months, average employment growth was only 11,700, and the unemployment rate ticked up slightly. It looked like, maybe, the end of the expansion.

But no. In the months to October and November, employment growth was back to 47,700 a month, and the jobless rate moved down.

December and January brought decreases in employment. But it’s always difficult to draw predictions from these months. This year’s January numbers also came with an asterisk from the Australian Bureau of Statistics: a much larger number of persons than usual were classified as waiting to start work, raising the prospect of a healthy boost in employment in February, which is what has happened.

So if a labour market slowdown is underway, it is gradual and slow, rather than the “falling off a cliff” variety. For that reason, it’s likely to take a while longer to know exactly where we are heading.

But more young people are in jobs

Not everything about the labour market is unpredictable, however. On the contrary, most of the changes we’ve seen since mid-2021, once the Australian labour market started recoverng from the initial impact of COVID-19, are exactly what we would have expected.

When the labour market is growing strongly, we expect this will benefit most of the groups who usually face the biggest difficulties getting into work: those with lower skill levels, who live in regions with less employment opportunities, and young people. This is indeed what has happened.

The likelihood of those without a post-school qualification being employed has increased 2 percentage points between 2019 and 2022, double the 1-point increase for those with a Bachelor’s degree or above.

In the 25% of regions with the lowest rates of employment, the proportion with jobs in 2022 was 2.2 percentage points higher than 2019. That increase was about three times more than in the 25% of regions with the highest employment rates.

Since immediately before the onset of COVID, the proportion of people aged less than 25 in employment has grown by 6.3 percentage points, compared with a 1.9 percentage point increase for those aged 25 to 64 years.

And educational enrolments have fallen

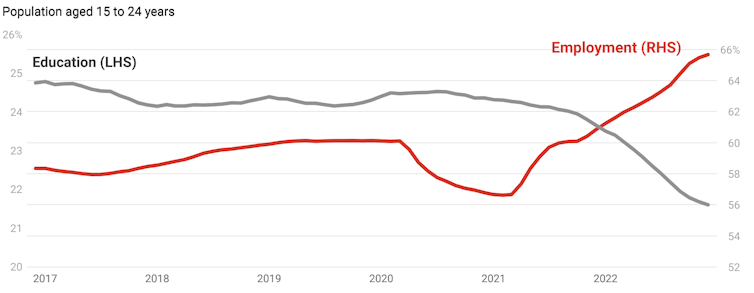

For the young, there has been another consequence of the strong labour market that we’ve learned to expect: more in jobs means fewer studying. Between February 2021 and December 2022 the proportion of those aged 15-24 in full-time tertiary education fell from 24.3% to 21.6%.

Employment vs education

ABS Labour Force

A similar withdrawal was observed in the late 2000s, during the mining boom, in the states of Western Australia and Queensland.

It’s having this past experience to draw on that, of course, makes it easier to see patterns in the impact of recovery, than to know where the rate of unemployment is about to head in coming months.