The introduction to Admissions states:

There is no way to neatly summarise what Admissions is or what it contains. If we were to write shorthand case notes to hand it over to you as a reader, they would say…

This is followed by a large paragraph of disjointed words, beginning with “Dolphins” and ending with “So many flipped moons”.

Review: Admissions, edited by David Stavanger, Radhiah Chowdhury and Mohammad Awad (Upswell Press)

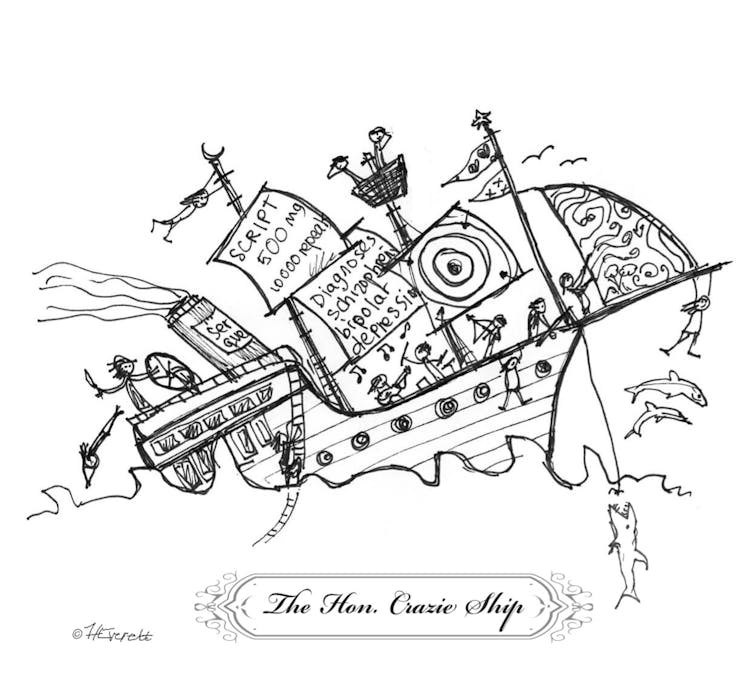

Admissions is not an organised collection of stories, nor a thematic discourse or commentary on mental health. It is difficult to read if you are expecting a linear progression of ideas.

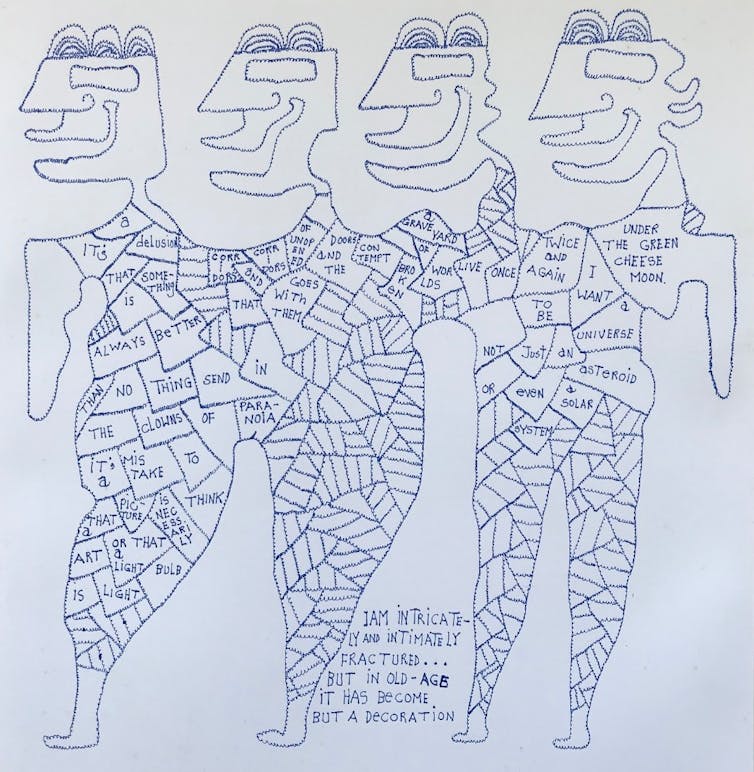

But overall, this is a text that can broaden our views on all sorts of aspects of mental health. The book contains a variety of perspectives from people with lived experience of mental health issues, presenting the content in a variety of ways including poems, prose, diagrams and sketches.

Upswell Publishing

Honest truths and deep pain

The honest truths about the deep pain suffered by many people with lived experience of mental health issues may be new to readers, even those working in healthcare. For example, Kobie Dee writes in Role Models about why alcohol and drugs bring some relief for pain – and how change is not possible without a role model. His story of how he learned to cope makes it obvious that change is truly challenging.

We get an honest view of the carer’s life in Roller Coaster by Kristen Dunphy, through in-depth descriptions of the awful experience and incredible sadness of being with a loved one who has episodes of despair and frantic behaviour.

The story, told by a wife, leaves the reader with the sense this relationship is doomed by the confusion and struggles in caring for a partner with mental health issues. The carer’s story is a rarely heard viewpoint in healthcare, but the views expressed by Kristen Dunphy are crucial to absorb.

The front cover is a commissioned piece of art by Amani Haydar (author of the memoir The Mother Wound, about the aftermath of her father’s murder of her mother – and one of the book’s contributors). It depicts a woman’s face, crying on one side, blank on the other: rays of light are emitted from the crying eye. The evocative image is open to many interpretations – and this is the hallmark of the whole book. The reader can see in it whatever they wish to see.

For example, take the intriguing title. Initially, the term “Admissions” brings hospital (or psychiatry ward) admissions to mind. However, in this book, it seems to apply to all kinds of aspects of life that people want to admit to experiencing, feeling and believing.

Upswell Publishing

We need to treat borderline personality disorder for what it really is – a response to trauma

Confronting complacency

The book begins with a short work by South Australian poet Manal Younus, titled “who is she”. This piece is a good place to start, as the poem creates an urge to self-reflect. The opening lines – “Who is she, the one who shares your face – but not your vision” – urge you to think about who could this be in your own life.

Booked Out

The many pieces in this book seem not to be structured together for a specific purpose. They are varied in length, style, even orientation: some pieces, like The Argument by Benjamin Frater and The Z-A of Crazy by Alise Blayney, are oriented in landscape style (rather than the usual portrait orientation). The initial effect is jarring; it keeps the reader from complacency.

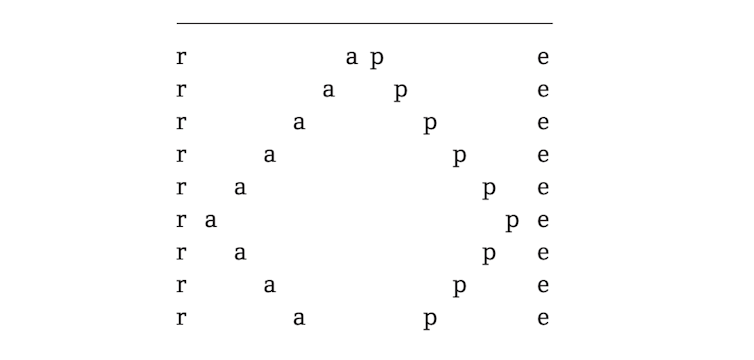

Sestina: Rape by Stuart Barnes includes a picture of the word “rape” spelled out in a confronting diagram, following a shocking story of a man’s repeated rape, and its denial by others. The presentation of the diagram is deliberately stark, to highlight the horror of what the author experienced.

The editors also contribute pieces. Chowdhury’s description of the secrecy about mental illness in Bengali culture is beautifully described. In one section, she writes:

There’s no one word for love in the Bengali language. A cursory google will reveal more than thirty words of varying nuance […] I trawled through the ones I know to find a suitable one to describe a mother’s anchoring grip.

Awad’s poem, Episode(s), cleverly and painfully illustrates the sense of gasping for oxygen during therapy and ends with:

I am still trying to convince

My lungs,

Oxygen has not left the room.

And Stavanger contributes seven brilliant paragraphs in his poem Suicide Dogs, which moves from describing dogs that leapt to their death in Scotland, to the many ways dogs prevent their owners from suicide.

From tough love to interventions, what works when a loved one is struggling with addiction?

Shocking reflections

There are some well known contributors to this book, including Torres Strait Islander singer Christine Anu (writing about being censored) and former Australian of the Year, and advocate for survivors of sexual assault, Grace Tame.

Tame’s contribution is a punchy poem, titled Hard Pressed, which compares the press and hungry hounds. Prolific author Sandy Jeffs has a piece called The Madwoman in this Poem. As always, Jeffs’ description of her experiences is written without fear or favour, giving the reader a clear sense of her own journey through episodes of psychosis. She graphically depicts experiencing beliefs that famous people can read her mind, and that she can feel spiders eating her brain, as well as fears her head is about to explode.

‘There is great strength in vulnerability’: Grace Tame’s surprising, irreverent memoir has a message of hope

Many of the pieces in Admissions may shock readers who have not read poems or pieces like this before, where rape, deliberate self-harm and suicide form the key content.

Images of one’s own dead body, as depicted in Bones by Luka Lesson, are difficult to deal with. Many pieces will sadden or frustrate. This is not a book to read lightly, or once, or in its entirety in one go: it requires several readings, at different times of life. It requires reflection between pieces.

Upswell Publishing

Admissions presents a kaleidoscope of emotions that shift with your own state of mind, as I found when I read this book over time.

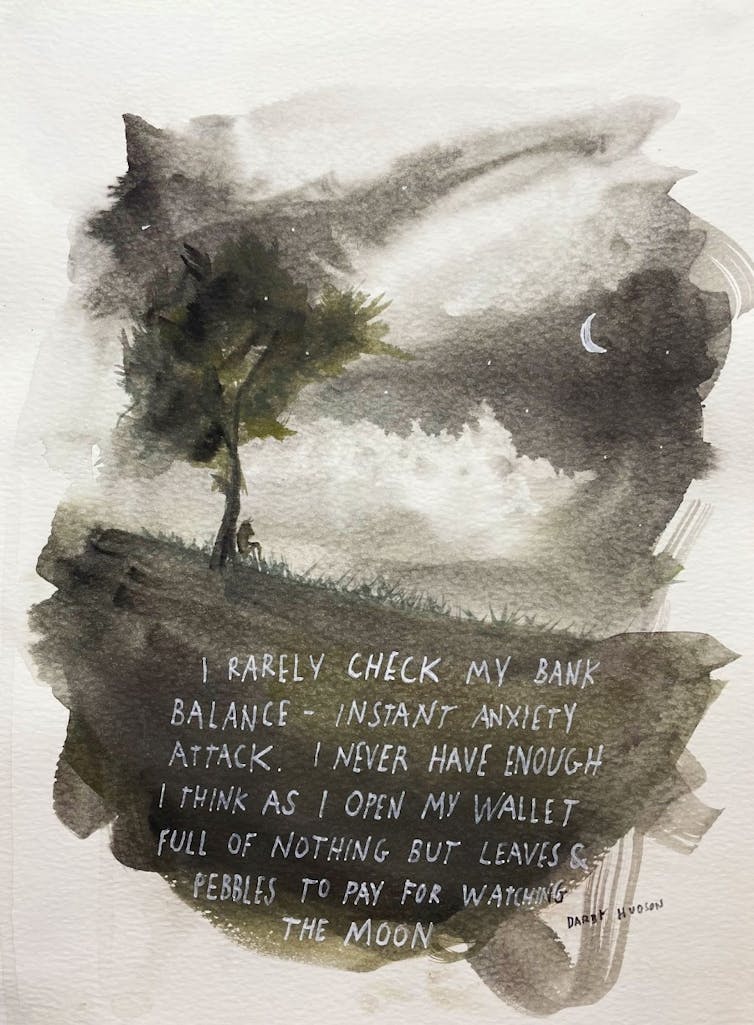

Some hit me with ferocity (like Flesh by Hope One), while others moved me to tears (People Die in Seclusion Rooms by Anna Jacobson) – or to rage on behalf of the author (The Queue by Rebecca Rushbrook), or to chuckles (100 Points of ID To Prove I Don’t Exist by Darby Hudson. I was bamboozled by some pieces, like Paleochannel by Omar Musa, but I decided the author would like us to live with that confusion.

This book is not mainstream, and not for everyone – but I am glad it exists. I urge you to read it and get what you want from it. Then reread it later, and I bet you will get something different!