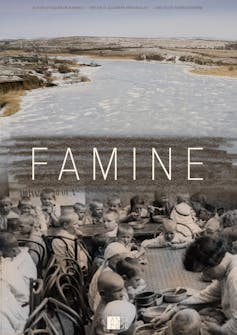

In October last year, Russia banned a documentary depicting the famine that hit parts of the Soviet Union including Ukraine between 1921 and 1923 and revoked the film’s screening licence. Now the film is to have its UK premiere (with English subtitles) on June 22 in east London.

Famine is an artistically sophisticated but in many respects unremarkable historical documentary. It does a good job of telling viewers about its subject, which is not one familiar to the Russian public, despite being one of the most traumatic events in the country’s history and worst famines of the 20th century. It killed approximately 5 million people and would have been worse but for an international relief effort led by the US.

Russian ignorance is no accident: the Russian education system and media deliberately avoid this topic. Indeed, it is a surprise the film was even made.

I spoke to the film’s originator, the Russian journalist and scholar Maksim Kurnikov in May 2023. He explained that he decided to start work on the film in 2014, after witnessing the destruction of food confiscated for contravening Russia’s counter sanctions against western imports in the aftermath of the invasion of Crimea.

The project faced frequent obstruction as Russian museums and archives were often closed to the filmmakers. Its budget came entirely from crowdfunding, with over 2,000 contributors.

While the filmmakers never received any explanation for the ban, Kurnikov explained to me that, in his view, Famine’s positive depiction of the west helping to feed Russia from humanitarian motives, undermined the Russian media.

Their repeated message is that Russia has always been a great power, relying on itself and never on help from others. It prefers to draw attention to the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union during the second world war, presented as a unifying, heroic episode.

Antipode Sales International, LLC

But there is a further historical reason for the ban. The appeal to the international community for famine relief stands in sharp contrast to Joseph Stalin’s collectivisation of agriculture from 1932-1933, when he and Communist party officials deliberately decided to let millions starve, primarily in Ukraine, to crush potential resistance to Moscow’s dominance.

This later famine has been termed “the Holodomor” by Ukrainian historians and is a key event in Ukrainian national memory and one that is increasingly seen as a genocide, though this is denied by Russian media. Kurnikov’s Famine film is an unwelcome welcome echo of the Holodomor.

Famine’s international reception

Since the ban, more than 2 million viewers have watched Famine online, after it was screened on the US-funded Russian-language internet channel, Current Time.

It also won the audience prize for best documentary film in the online programme of the biggest documentary film festival in the former Soviet Union, ArtDocFest (now held in Riga, Latvia). The film is now being shown around the world at film festivals and public screenings, garnering praise and awards.

The upcoming London screening suggests a further echo with the past. The famine of 1921-1922 marked an important stage in the development of humanitarianism. It was the first use of film in a humanitarian relief campaign to raise public funds, pioneered by Save the Children Fund.

This was the beginning of modern humanitarianism, where the public was encouraged through the latest tools of persuasion and advertising including documentary film, to give money to save the lives of distant strangers, unconnected by ties of citizenship or religion.

Antipode Sales International, LLC

The novelty was that the British public were being asked to save the lives of children innocent of the errors and crimes of the hostile Soviet regime. In east London in particular, there were well attended screenings for famine relief efforts in 1922, including in the People’s Palace on the site of today’s Queen Mary University of London.

There, the newly elected, first Labour mayor of Stepney, Oscar Tobin, made an impassioned appeal for donations, stating: “This was the first attempt made in Stepney to link the people with the suffering of those abroad.”

Famine doesn’t address this aspect of the relief efforts, partly for reasons of narrative economy, as there were a huge number of organisations involved in the providing aid. Herbert Hoover’s American Relief Administration provided the lion’s share, paid for by the US Congress, in the hope not only of saving lives but also of saving Europe from communism.

Nevertheless, watching Famine, revisiting this historical event and the media campaign to raise money for famine relief through film, shows how far humanitarianism has come in the last 101 years. Amid a “cost of giving” crisis, with a steady decline in charitable donations, it also questions whether the British public are still moved by films of distant suffering.