It is 2019. There is a virus lurking in China. The Chinese Communist Party (CCP) is warning that if it is not contained, it could infect the entire country. It could turn the country upside down. Tear at the social fabric. The CCP’s dream of harmony cannot withstand this. So they tell their people: this must be wiped out. Memories are too fresh in China of what happens when things spiral out of control.

China is a nation that barely hangs together. Throughout time, empires have risen and fallen. Bloodshed beyond imagining – on a scale almost unseen in human history – marks each turn in China’s fate.

The hundred years between the mid-19th century and the Communist Revolution in 1949 were brutal. The Opium Wars with Britain, the fall of the Qing, the Taiping Rebellion, the Boxer Rebellion, the civil war between nationalists and communists, the Japanese occupation – tens of millions were slaughtered.

The CCP knows it should fear its own. It knows what happens when people rise up. The party seeks stability, but stability can only come with force and threats. Nothing can be tolerated that strays too far from the reach of the party.

Now, a virus is loose. In 2019, the world is not watching. Not really. Some warn of what is happening, what is to come. But who listens? It is too far away. We are trading with China and we grow rich as China grows rich.

So, the Communist Party goes to work in secret. It is rounding up people infected with the virus. It is locking them away in secret facilities. Prisons. Isolating them. Choking off the virus at its source. Nothing short of elimination will do.

Explainer: who are the Uyghurs and why is the Chinese government detaining them?

An ideological virus

This virus has a name. Uighur. Many, if not most, in the West cannot spell it. Nor can they pronounce it. Uighurs. Muslims. A people in the outer western regions of this vast country. People who have been yearning to be free. Who speak their own language. Practise their culture. Pray to their god.

They are a virus. At least, that’s what the CCP calls them.

The Communist Party transmits “health warnings”. As reported by Sigal Samuel in The Atlantic, and translated by Radio Free Asia, it aims them at Uighurs via WeChat, a popular social media platform in China:

Members of the public who have been chosen for re-education have been infected by an ideological illness. They have been infected with religious extremism and violent terrorist ideology, and therefore they must seek treatment from a hospital as an inpatient […] The religious extremist ideology is a type of poisonous medicine, which confuses the mind of the people […] If we do not eradicate religious extremism at its roots, the violent terrorist incidents will grow and spread all over like an incurable malignant tumour.

In 2018, Human Rights Watch released a report, titled Eradicating Ideological Viruses. The warnings are there. Even if the world is slow to wake to them. The report says:

Perhaps the most innovative – and disturbing – of the repressive measures in Xinjiang is the government’s use of high-tech mass surveillance systems. Xinjiang authorities conduct compulsory mass collection of biometric data, such as voice samples and DNA, and use artificial intelligence and big data to identify, profile and track everyone in Xinjiang.

The authorities have envisioned these systems as a series of “filters”, picking out people with certain behaviour or characteristics that they believe indicate a threat to the Communist Party’s rule in Xinjiang. These systems have also enabled authorities to implement fine-grained control, subjecting people to differentiated restrictions depending on their perceived levels of “trustworthiness”.

Christina Larson/AP

Note the language. Biometric data. Voice sampling. DNA. This is ideological and it is biological. People are treated as viruses that transmit illness. If not stopped, they will threaten us all, is the message.

Human Rights Watch says in the name of stability and security, authorities will “strike at” those deemed terrorists and extremists, to rid the country of the “problematic ideas” of Turkic Muslims. Not just Muslims, but anyone not expressing the majority ethnic Han identity. As Human Rights Watch says: “Authorities insist that such beliefs and affinities must be ‘corrected’ or ‘eradicated’.”

This is not new. What the CCP is doing is what other tyrannical regimes have done. They seek to create what’s been called a “harmony of souls”. They want nothing less than to produce the perfect, subdued, sublimated human. Compliant. Passive.

In the words of Joseph Stalin: “The production of souls is more important than the production of tanks.” Historian Timothy Snyder says the Nazi and Soviet regimes turned people into numbers. And tyrants everywhere have used the language of germ warfare. They define their enemies as diseases or infections and they seek to inoculate their own societies.

Authoritarian regimes seek to sterilise and “purify” society. Listen to them.

Stalin’s henchman Vyacheslav Molotov spoke of purging or assassinating people who “had to be isolated” or, he said, they “would spread all kinds of complaints, and society would have been infected”.

The architect of Hitler’s Holocaust, Heinrich Himmler, in sending millions to the gas chambers, said he was exterminating “a bacterium because we do not want in the end to be infected by a bacterium and die of it”. He said: “I will not see so much as a small area of sepsis appear here or gain a hold. Wherever it may form, we will cauterise it.”

And then there is Adolf Hitler, who compared himself to the famed German microbiologist Robert Koch who found the bacillus of tuberculosis. Hitler said,

I discovered the Jews as the bacillus and ferment of all social decomposition. And I have proved one thing: that a state can live without Jews.

To Hitler, Jewish people were “no longer human beings”. He described the Holocaust as a “surgical task”, “otherwise Europe will perish through the Jewish disease”.

It is no mistake these regimes use the language of virus, disease and contamination. Just as a virus is to be eradicated, so too people are to be removed, eliminated or exterminated. These attitudes do not belong to a time past. There are leaders today who exploit the same fears, who focus on difference and create division using the same language of disease.

Remember what Donald Trump said of Mexican immigrants? That they are responsible for “tremendous infectious diseases pouring across the border”.

And in China, the Communist Party has locked up a million Uighur Muslims in “re-education camps”, where human rights groups say they are brainwashed with Communist Party ideology. A virus to be eradicated.

UN report on China’s abuse of Uyghurs is stronger than expected but missing a vital word: genocide

Virus of tyranny

The virus of tyranny has haunted our world. Albert Camus warned us of this in his novel The Plague: the story of a rat-borne disease that overruns an entire city. His was a bleak vision of death and fear, of a city sealed off and a people locked down, then shot when they tried to escape.

Written in 1947, just two years after World War II, when the West was still celebrating the victory of freedom, Camus’s plague is an allegory of authoritarianism.

Camus wanted to tell us of the courage that swells within us, that when the plague was at its worst, brave people fought against it. But he cautioned us, too, that the plague can return. It is “a bacillus that never dies or disappears for good”, but bides its time “slumbering in furniture and linen”. It waits patiently “in bedrooms, cellars; trunks, handkerchiefs, old papers”, until one day it will rouse again.

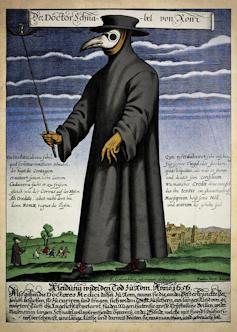

Paul Furst/Wikimedia Commons

In coronavirus, tyranny may have found the perfect host: a fearful population and all-powerful government. French philosopher Michel Foucault long ago made the link between the plagues of the 17th century and authoritarian control.

Behind state-imposed discipline, he wrote, “can be read the haunting memory of contagions”: not just the memory of a virus but of rebellion, crime, all forms of social disorder, where people “appear and disappear, live and die”. It is the state that brings order to the fear: “everyone locked up in his cage, everyone at his window, answering to his name and showing himself when asked”.

In the response to the plague, Foucault saw the forerunner of the modern prison: the panopticon; the all-seeing eye.

The plague-stricken village, wrote Foucault, is

traversed throughout with hierarchy, surveillance, observation, writing; the town immobilised by the functioning of an extensive power that bears in a distinct way over all individual bodies – this is the utopia of the perfectly governed city.

The coronavirus shutdowns remind us freedom is the province of the state. The crisis has centralised government control. Around the world, governments have used physical and biological surveillance to control the pandemic. To eradicate the virus.

We have all become, to varying degrees, a little bit like China.

Guide to the Classics: Albert Camus’ The Plague

A strange illness in Wuhan

Coronavirus emerges out of China in the dying months of 2019. I remember reporting on it. A strange illness is being detected in the city of Wuhan. Dozens of people are being treated for pneumonia-like symptoms. In January 2020, there is the first reported death. Then quickly, deaths in Europe, the United States, South Korea, Japan, Thailand.

We are still so blasé. It feels so far away. We have seen this before, haven’t we? SARS, swine flu, Ebola. They come and they go. Life goes on. We go to the beach. We get on planes. We have parties. And if we have a cough or feel a bit under the weather, we most likely still go to work.

We don’t realise what is happening. I am on ABC’s Q+A program in February 2020. Footage is shown of lockdown in Wuhan. People are barricaded in their apartments while police forcibly remove and restrain. The audience is appalled.

It couldn’t happen here, could it? An epidemiologist on the panel says, actually, yes. We have laws to allow for just these extreme emergency measures. Surely though, we agree, it isn’t likely.

Roman Pilipey/EPA

On the same program is China’s deputy ambassador to Australia, Wang Xining. Minister Wang, as he is known, is an old acquaintance. A sparring partner. When I was based in China for CNN, he was my minder. He was appointed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to watch everything that I did.

In China I was arrested and detained, taken to Chinese police cells for doing stories the authorities did not approve of. I was, on several occasions, physically attacked and beaten. My family was under constant surveillance. Now the man responsible was sitting next to me in an ABC studio.

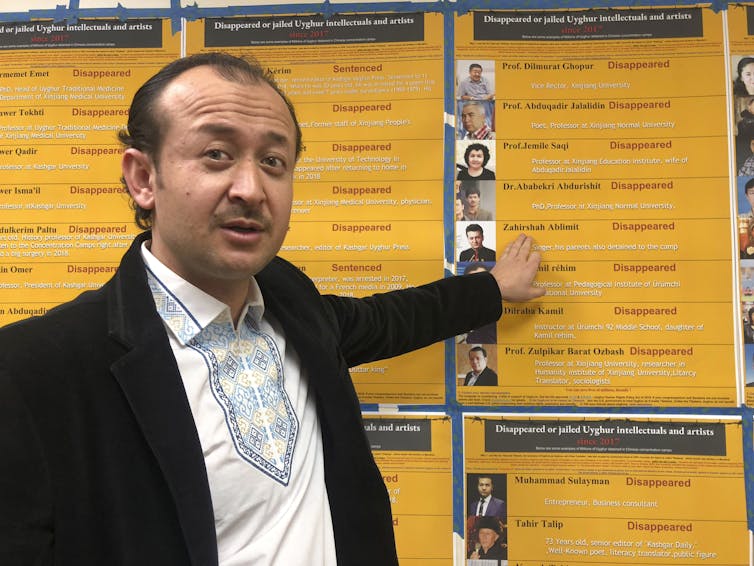

In the audience, a Uighur man asks a question. He was separated from his wife and child. He had come to Australia ahead of them, hoping to settle and secure visas so they could follow. He didn’t know where they were. He had family in the Chinese “re-education” camps. He was clearly worried.

Minster Wang defends the China COVID lockdown. And he defends the lockdown – soon to be called the genocide – of the Uighurs.

In this moment were twinned the two crises – the two “viruses” – threatening our world. COVID-19 threatened our health. Soon, we would indeed follow China’s lead and introduce lockdowns. And the virus of tyranny was spreading.

In 2020, as COVID crossed borders, so, too, did tyranny. Liberal democracy was in retreat. Freedom House, which measures the health of democracy, now counted 15 straight years of democratic decline. From the post–Cold War boom, freedom was now being crushed.

Within democracies, too, people were falling under the sway of autocrats and demagogues. This had been a slow burn. Growing inequality, war-fuelled refugee crises and a blowback against globalisation had eroded trust. The poor and left-behind felt abandoned.

The devil dances in empty pockets. From the early 2000s, anti-immigration attitudes grew. Racial division became even more stark. Far-right parties made a comeback in Europe as barbed wire went back up on borders. People wanted their countries back and they were primed for populists. Türkiye’s Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, India’s

Narendra Modi, Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro – all would come to power. Each spouted easy solutions to complex problems. Each divided to conquer.

Into the picture came a political circus act. A Manhattan real estate billionaire and reality television star. Donald Trump styled himself as the anti-politician. He promised to “drain the swamp” and “make America great again”. Eight years of the first Black president of the United States, Barack Obama, ended in 2016 with the election of a man who exploited racism.

To populists, COVID-19 initially was a boon. They seized on it to strengthen their grip on their countries. This was the state of the world in 2020, when the virus took hold. This was a perfect storm. A virus that robbed us of our freedom just as democracy was imploding and freedom was in retreat. And China was proudly boasting that its authoritarianism was ascendant.

If the 20th century was a triumph of democracy, the 21st century, to China’s Xi Jinping, would crown the China dream.

‘Kafkaesque’ true stories of ordinary people: inside the first days of COVID-19 in Wuhan, China

Plagues, political repression and violence

Plagues have historically been a harbinger of political repression and violence. The Spanish flu after World War I contributed to the rise of the extreme right in Germany. The Black Death in the 14th century unleashed violence against Jews.

Sydney University Professor of Jurisprudence Wojciech Sadurski, in his book A Pandemic of Populists, says COVID has been a “powerful accelerator of many of the pre-existing trends, both negative and positive, in business, culture and politics”.

Populist leaders declared states of emergency and, as Sadurski writes, pushed them “well beyond the limits of the necessary”. Viktor Orbán set aside parliament. He was a one-man government. People critical of him could be arrested. In the Philippines, as in India, police were given powers to detain anyone “spreading misinformation” or inciting mistrust.

Sadurski points out that, in most cases, these authoritarian leaders used militaristic language. Fighting COVID was a war. The people were conscripted.

Tomas Kovacs/AP

Xi Jinping is not a populist leader. He doesn’t seek legitimacy at the ballot box. He is an authoritarian. And he believes his system is better. To Xi, the battle against coronavirus is also a war: a “people’s war”.

It has been a war without end. Xi cannot allow the virus to win. Long after lockdowns passed elsewhere, Xi continued to keep a stranglehold on COVID flares. It has weakened the economy. It is straining nerves. People are angry. There have been protests. Some are even calling for Xi to go.

But Xi has strengthened his grip. By altering the constitution and scrapping two-term presidential limits, he is now leader for life. Under cover of fighting COVID, he has used enhanced surveillance and tracking technology to peer into every part of people’s lives. The COVID crackdown coincided with crushing democracy in Hong Kong. He has arrested dissidents. Silenced rivals. He is threatening war on Taiwan.

And Uighurs remain a target. Still a “virus” to be eliminated.

A hinge point of history

We are at a hinge point of history. Thirty years after the end of the Cold War, there is talk of Cold War 2.0. The United States is staring down a new rival: China. We are witnessing a return of great power rivalry. It is a supercharged great power rivalry.

China is more powerful today than the Soviet Union was then, and the United States is unquestionably diminished. America is politically fractured, it is deeply divided along racial and class lines; it has an epidemic of gun violence and it has been devastated by coronavirus.

Donald Trump thought he was bigger than COVID. He was slow to act, he was dismissive and his populism was eventually revealed as reckless. Yes, he fast-tracked vaccine research and production. But he was a master of mixed messaging and so much damage was done. At the time of writing, in the United States there have been more than 100 million cases and one million deaths. The only country to reach that number. Trump lost office.

zz/Dennis Van Tine/STAR MAX/IPx/AP

By contrast, Xi Jinping is entrenched in power. The country where COVID first emerged is the world’s biggest engine of economic growth. It is on track to usurp the United States as the single biggest economy in the world. It is extending its influence and economic reach via the Belt and Road Initiative, the biggest investment and infrastructure program the world has ever seen.

Xi is building an army to match his economic might. And he is leading the way on artificial intelligence research. The numbers tell the story. In the 20 years between 1997 and 2017, China’s global share of research papers increased from just over 4 per cent to nearly 28 per cent. And what is it focusing on? Speech and image recognition. The Chinese Communist Party can track anyone, anywhere, anytime.

Technology was meant to liberate us. Some saw the death knell for authoritarian regimes. How can you control the internet? But China has. Cyberspace has become a tool of tyranny. China has taken the digital age and put it in service of genocide.

There are lessons here for journalists. Our job is not to simply report events, it is to connect them. To join the dots. To reveal the big forces at play in our world. We missed this opportunity.

We cannot understand the COVID pandemic and its impact without understanding the currents shaping our world. COVID emerged out of China at a time when Xi Jinping had his eyes on global supremacy. He had shown how far he would be prepared to go to “harmonise” the nation. He had trialled his lockdown measures on what he callously called the “virus” of the Uighurs.

Around the world, democracy was in retreat and authoritarianism on the march. And now a virus was spreading that would attack the liberal democratic West where it believed it was strongest: its freedom.

Media can so easily be overwhelmed by events. One of the most common failings – particularly of television – is to report what we see, not what it means. Images can drive coverage. And images of people in white suits locking down entire cities obscured what was even more important. COVID was a 21st-century virus; a virus of a globalised world, of high-speed travel and borderless trade. It was also a virus of an increasingly authoritarian world.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a stress test. It revealed and accelerated fault lines already there. Populists were stripped bare. Their slogans, easy answers and arrogance meant they were slow to act. Millions died who might otherwise have lived. In strong democracies where there is trust in science and authority, countries emerged stronger. Yet they, too, walked a fine line between surrendering liberty and saving lives.

In China, Xi Jinping believes the People’s War is a victory for the Communist Party. The Party – the all-seeing eye – can control everything. It sits at the heart of everything. Xi believes he is the fulfilment of prophecy. The man who follows the great leaders, Mao Zedong and Deng Xiaoping. The one who delivers on China’s greatness.

Xi walks a tightrope, too. He has strained the nation to breaking point. The relentless, cruel lockdowns have slowed the economy and crushed the spirit of Chinese people. And they are angry and rising. China, like the rest of the world, is also reaching a tipping point.

In December 2022, Xi felt the pressure from the Chinese people, following mass demonstrations and unrest, and lifted the lockdowns abruptly. COVID quickly ran rampant. However, though the COVID lockdowns have ended, the Uighurs continue to suffer.

The virus of tyranny sleeps within democracy, too. It has always been in our bloodstream. China has edged us, the democracies, closer to what political scientist Vladimir Tismaneanu has called “the age of total administration and inescapable alienation”.

The COVID pandemic has passed, at least as a political crisis. Our minds are turned now to war in Ukraine and economic strife. But journalists must remember that, as in contagions past, COVID will shape us. It leaves behind the trace of tyranny. And that is the true virus. The virus that will not die.

This is an edited extract from Panemedia: How Covid Changed Journalism (Monash University Press).

This essay was originally written in November 2022.