The federal government recently announced its intention to amend the Expungement of Historically Unjust Convictions Act to expand the list of offences Canadians can apply to have struck from their criminal records. The list now includes abortion-related offences and indecent acts in a bawdy house.

We are a group of gay and lesbian historians who study the criminalization of queer communities in Canada. While we applaud changes that allow women and abortion providers to apply to have their records expunged, we question the partial and historically faulty way the government has added bawdy-house offences to the act.

Sex workers charged with bawdy-house offences, for example, remain excluded from accessing the expungement process.

In other words, if a bawdy-house conviction was only about indecency, people can now apply to have their records expunged. But if there are any allegations of sex work related to their convictions, they cannot.

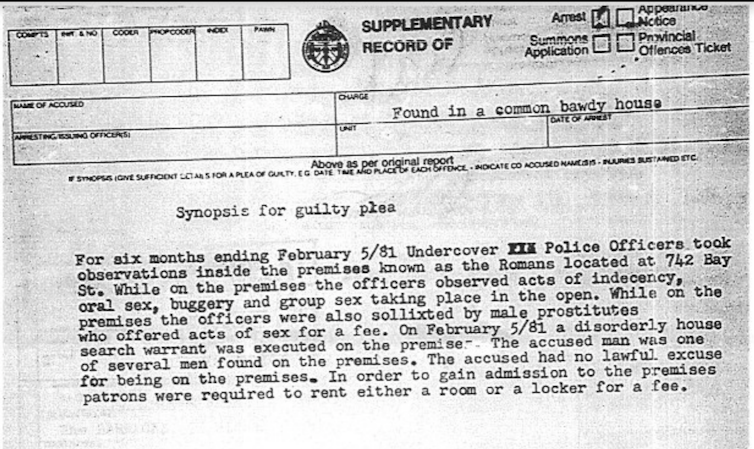

However, police often alleged both indecency and sex work were taking place inside the bawdy houses.

And so in the government’s view, bawdy-house laws may now be historically unjust, but only for some.

Toronto Police via Freedom of Information request, Author provided

Flawed act, limited uptake

In 2018, the federal government passed Bill C-66, which established a process to expunge the records for those who had been convicted of historically unjust offences. This was part of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s apology to queer people in Canada.

During debate on the bill, we argued that it failed to fully carry out the prime minister’s apology because it included only two offences — buggery/anal intercourse and gross indecency, a small fraction of the Criminal Code provisions that have historically targeted queer people.

It left out bawdy-house laws, indecency, vagrancy and criminalization for HIV non-disclosure. We also argued the application process was too onerous.

Turns out, we were right. In the first three years of the act, a paltry nine expungements were granted. This represents an exceedingly small number of those who have been unjustly charged.

According to updated Parole Board information recently emailed to us, the Record Suspension Division has received 70 applications for expungement, with still only nine granted. Sixty applications have been refused, primarily because the convictions were not on the list of eligible offences for expungement.

Pride and prejudice: With only 9 LGBTQ criminal record expungements, what’s to celebrate?

History of criminalization

The recent changes amend Bill C-66 to broaden the range of expungable offences by adding, in addition to abortion, “indecent acts” committed in bawdy houses. This is possible because the bawdy-house law was repealed in June 2019, something we argued for at the time.

Why, then, has it taken the government so long to add this to the list of expungable offences?

The government decision to specifically exclude sex workers from expungement ignores the fact that in 2013, the Supreme Court of Canada struck down the bawdy house law in relation to sex work. It’s also a serious misunderstanding of how marginalized sexual and gender communities have been criminalized and policed historically.

In 1917, the Criminal Code definition of a bawdy house was expanded to encompass not just prostitution but also other “indecent acts.” This set the stage for the police to use the bawdy-house law to both punish sex workers and arrest men caught up in bathhouse raids.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/UPC/Gary Hershorn

Despite the long historical overlap in the policing of sex workers and gay men, the government is making a distinction between the indecency clause of the bawdy-house law and the parts of the law that pertained to the exchange of sex for money.

As historians, we have a deep appreciation for the historical links in the policing and criminalizing of sex workers and gay men. This shared history informs our criticism of the government’s attempt to single out gay men as worthy of expungement while leaving sex workers out in the cold.

New divisions, old problems

Because the arrest records of men charged with indecent acts in a bawdy house often include police allegations of sex work in their records, their applications for expungement would be ineligible.

This sets up another division between the deserving and undeserving — between men whose historically unjust conviction makes no reference to sex work and those whose records do, accurately or not.

In addition, those wishing to clear a record of “indecency” must prove the indecent act took place in a bawdy house. However, the vast majority of indecency convictions stem from police entrapment of men in public parks and washrooms.

(Shutterstock)

Even though men take great care to construct privacy for themselves so as not to bother others, none would qualify for an expungement because the indecency took place in “public” and not in a bawdy house.

The government’s very narrow definition of indecency fails to include most people charged with this offence.

On top of these newly created problems with the Expungement Act, many obstacles in the existing process remain. For example, people who were convicted but received a discharge at sentencing are not eligible for expungement, despite the fact their records continue to hang over them.

What’s more, all the onerous requirements of the expungement application, which place the burden of proof on the applicant, also remain.

Justice for all

Back in 2018, the Senate Committee on Human Rights urged that as soon as the Expungement Act was passed, the government should consult with community members and experts to review remaining discriminatory historical laws. The committee specified “prostitution-related offences.”

Five years later, the government has still not consulted with those who know this history best. Instead, it introduced changes that are historically unfounded, extremely limited in scope and seek to divide sexual and gender communities.

As historians of sexuality, we argue that the historical record supports sex workers’ organizations and their demand that the government include bawdy-house convictions related to prostitution in expungement legislation. These convictions disproportionately affect women of colour, Indigenous women and transgender people.

And so, in 2023, we once again call upon the federal government to provide meaningful access to criminal record expungement for all — queer people, sex workers, trans and non-binary people — who have been convicted of historical offences for consensual sex.