Our understanding of ourselves is woven together with threads of time: a concept deeply entangled with power, culture and identity. Time is not a neutral concept.

Historically, time has acted as a tool of oppression and marginalisation. Colonial notions of “civilisation” were linked inescapably to the prudent use of time. So on the one hand, time is an objective measurement derived from observation of phenomena. On the other, it has been a cultural artefact, wielded to dehumanise Indigenous peoples. Their societies have been depicted as “time-less” – and therefore inferior.

The coloniality of time, and the society we have built around it, is the subject of the first short story in Dr Mykaela Saunders’ engrossing collection of Aboriginal-centred speculative fiction, Always Will Be.

Review: Always Will Be – Mykaela Saunders (UQP)

In Taking our Time, a future Goori community in the Tweed assert their sovereignty by confiscating all the clocks, reclaiming – and reasserting, as they do so – Goori understandings of space and time. They directly challenge the centrality of quantifying, and accounting to, linear time.

The short stories in Always Will Be each take place in an alternate future version of the Tweed. Each story is infused with a clear and critical insight into Indigenous ways of being, knowing and doing, linked comprehensively and beautifully to the future place where their events unfold. The stories are seamlessly blended with echoes of history and the realities of colonisation, skilfully explored and critiqued through these imagined futures.

In Fire Bug, young Tyson travels on a high-school camp to his country. It’s Country he has been disconnected from, because of his schooling and living situation. On camp, Rangers teach the students about fire and burning practices. At one stage, in an attempt to teach the students how to light fire the proper way, another student, Betty, observes “yeah but we got lighters and stuff now”. This is a relatively minor component of the story – but it stood out particularly to me.

This one exchange foregrounds, with precision, the challenges faced by Tyson, his family and the Rangers who will set out to help him. Communities face difficulty in passing on cultural knowledge, and not only from imposed systems of outside control. There are also challenges in passing that knowledge from within, to youth born and growing up between worlds.

Each of the stories in Always Will Be includes examples like this. On one hand, a clear articulation and respect for the expression of culture and connection to place. On the other, an equally clear-eyed engagement with the complexities of colonial legacies. The stories invite both Indigenous and non-Indigenous readers to reflect and imagine Aboriginal sovereignties – and to do so in ways that honour the wisdom of Aboriginal knowledges.

The first Australian First Nations anthology of speculative fiction is playful, bitter, loud and proud

‘Powerful validation’

Always Will Be consists of 16 stories. Each story has made me stop and think. Sometimes it’s with a realisation of shared experience – I draw connections and see similarities.

Other times, I recognise a concept that I knew academically, politically, historically or culturally – but reading these stories, I experience the concept as it plays out, or is extended or engaged with in ways I hadn’t necessarily expected.

For example, The Girls Home begins with Jalah waking up from a nightmare inside a facility under guard. The facility is revealed to be a factory where girls are kept and exploited for their labour and bodies. After plotting an escape with other girls in the home and putting that plan into action, the story shifts dramatically.

What felt predictable and known was not as it appeared. The girl’s Elders were testing them. We are left to question the future relationship between Indigeneity and trauma: what will it mean to be connected to community and culture when disadvantage gives way to privilege?

In moments like this, I found myself stopping to ponder. Paragraph by paragraph. Line by line. Yet at other times, I was engrossed, racing to the story’s conclusion.

For Indigenous readers, these stories can serve as a powerful validation of their lived realities. They offer the opportunity to see a representation of our culture and perspectives represented in literature. Through Saunders’ short stories, Indigenous traditions and struggles are honoured and celebrated, fostering a sense of empowerment and belonging. These stories invite readers to challenge dominant colonial frameworks, binaries and deficit discourses.

For non-Indigenous readers, Always Will Be is a compelling invitation to confront their own misconceptions. By immersing themselves in the richly textured worlds crafted by Saunders, non-Indigenous readers are invited to witness assertions of Aboriginal sovereignties, and experience actions that embody them. The stories serve as a catalyst for understanding, encouraging readers to engage with Indigenous perspectives.

For example, in The Fisherman’s Story, the Goori protagonist is asked to assist with an fungal outbreak in a fish farm. After witnessing the methods employed, he thinks to himself:

We heard whispers about their strange beliefs but did not know whether they were true or not. No wonder these fish were always dying; it only appeared to be a scientific method. These practices were based on a charlatan system. Still, I bit my tongue for the time being.

Because Saunders centres Indigenous perspectives, the focus of examination becomes non-Indigenous practices, beliefs and knowledge systems. And these non-Indigenous practices, beliefs and knowledge systems are problematised. Indigenous sovereignties are then enacted, to find solutions within Indigenous knowledges.

Friday essay: 30 years after Mabo, what do Australia’s battler stories – and their evasions – say about who we are?

Imagined futures

The unpublished manuscript for this collection was awarded the 2022 David Unaipon Award for Emerging Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander writers – and it is not difficult to see why. The stories in Always Will Be started as the creative component of a Doctor of Arts degree, and they have been crafted with care. Each introduces its characters and place with clarity, depth and feeling.

But these imaginings must also be understood as just that: imaginings. As Saunders makes clear in Bugalbeh!, she is not writing history, nor is she sharing specific cultural knowledge.

As she states in Bugalbeh!, the collection’s conclusion: “I’ve imagined futures, and so the cultures in these stories are just as made up as the rest of the world building is”.

Instead, Saunders is, through creativity, creating space to explore different climates and politics – and to imagine alternatives to the business-as-usual state of Aboriginal relations. Published in the year following the failed referendum, when there is a lack of clear policy direction from the Australian government, this is a very timely endeavour.

Within the broader landscape of speculative fiction, Saunders’ work represents an important intervention. She injects Indigenous perspectives and worldviews into a genre often dominated, at least in the published form, by Eurocentric imaginaries.

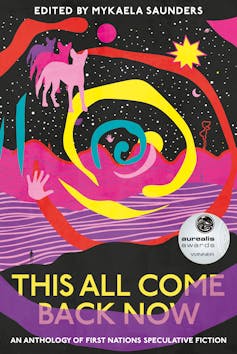

In doing so, Saunders’ builds on their recent work editing the groundbreaking 2022 collection, This All Come Back Now, the first published anthology of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander speculative fiction. Its contributions were from both emerging and established Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander writers.

Always Will Be exemplifies the power of literature to both reflect and shape cultural landscapes. Saunders not only contributes to expanding the scope of speculative fiction, but also challenges readers to reconsider whose stories are deemed worthy of speculation and exploration.

The stories in Always Will Be were crafted with care, respect and humour. They are in equal measures enlightening and entertaining. This collection is a must-read in 2024.