The Japanese singer MISIA discusses an exhibition of drawings that reveals the lives and feelings of children in Africa.

Courtesy of MUDEF

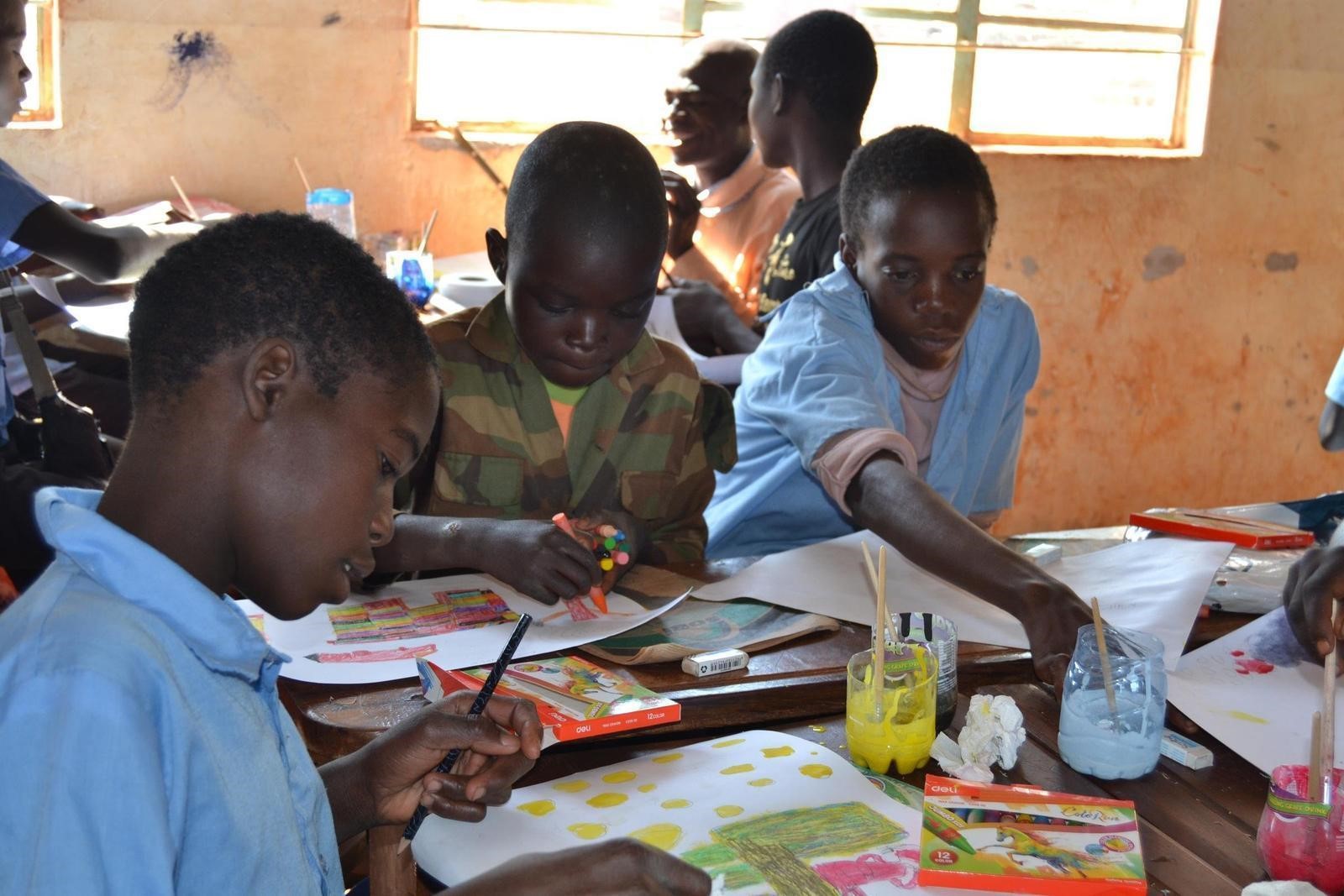

Tokyo Exhibits 249 Drawings by Kenyan and Zambian Children

Tokyo Station is known as the gateway to the Japanese capital. The Shin-Marunouchi Building, located right next door, became became home to the unique exhibition “MUDEF x Junior Artists MISIA Heart for Africa: Children’s Art Exhibition ‘My Precious Things.'” The show ran from August 8, 2022 through September 30, 2022, in connection with the Eighth Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD 8), which was held from August 27-28, 2022, in Tunisia. The Tokyo exhibition was organized by MUDEF (Music Design Foundation), which arranges social action activities with artists and other celebrities. It was planned with the full support of MISIA, one of Japan’s most iconic singers, and featured 249 drawings by Kenyan and Zambian children.

TICAD is a triennial event orchestrated by organizations including the Japanese government, the United Nations and the World Bank. Its purpose is to discuss topics related to African development with government officials from African countries.

MISIA made her music debut in 1998. She sang the Japanese national anthem at the Olympic Games Tokyo 2020. MISIA is passionate about social action and has worked to provide educational and other means of support to children in Africa. She is scheduled to begin her national tour “25th Anniversary ‘MISIA the Great Hope,'” which runs from November 14, 2022 to February 18, 2023.

Shintani Hiroko interviewed MISIA over Zoom about “MISIA Heart for Africa” and her experiences in Africa. The singer frequently visits the region to support local education. She also served as the honorary ambassador for TICAD 5, in 2013, and TICAD 7, in 2019, where she performed at “TICAD 7 Live Heart for Africa.” Donations from the proceeds of the 2019 concert were used to fund the Tokyo art exhibition. This interview has been translated from Japanese and edited.

Courtesy of MUDEF

One of the three schools that participated in this exhibition was Magoso School in Nairobi, Kenya. We’ve heard you’ve been supporting this school for 15 years.

When I first visited the school, in 2007, the youngest children were about 7 years old, and now they’re in their 20s. Some of the children have worked hard to become elementary school teachers or actors, and there’s even one who’s studying at a Japanese university to learn about education for children with disabilities. It’s incredible the power of education. It lets you build a future for yourself using just your own abilities. It lets you work, lets you feed yourself. A girl who studied in Japan told me, “Knowledge is the only thing that can’t be taken away from you. It will be something I treasure for the rest of my life.” I felt that was definitely true.

Courtesy of MUDEF

We’ve heard that two of the schools whose students’ work was included in the show were located in the Meheba refugee settlement in Zambia. One is in a district where the refugees live, and the other is in an area populated by former refugees who have settled in Zambia. Did you visit these schools, as well?

I visited the schools in 2019, when TICAD 7 was held. Zambia is a landlocked country that shares a border with eight other countries and is also relatively stable. So when there have been civil wars or other conflicts in the surrounding countries, the refugees have tended to flee to Zambia. I met with a family who said they had arrived at the settlement a week before I got there. They had walked for three months, crossed the border and were now in a situation where they were exhausted, with no money. It wasn’t just refugee children who were going to the elementary school in this refugee settlement. There were local children, as well, and all of the children said, like it was a motto for them, “We’re not here to fight—we’re here to study so we can all get along.”

Some refugees stay in Zambia because the Zambian government gives land to refugees who settle there, and so there are second- and third-generation refugees living there, as well. It’s not easy, but I think it’s one way to practice peace—to live alongside people from different countries. I think it could make life in Japan more meaningful if we could learn from people who have experienced hardships we couldn’t imagine. We hoped that this exhibition captured the public’s interest when it comes to these children.

Courtesy of MUDEF

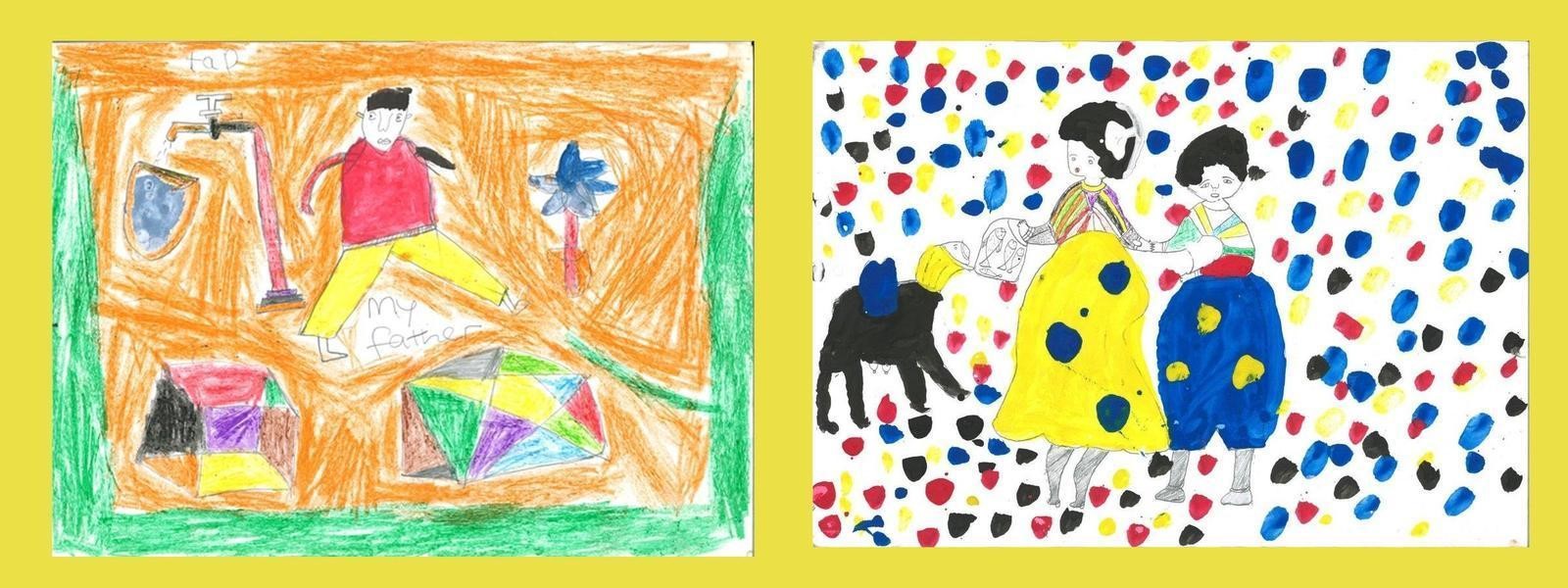

What was the impression you got when you saw the children’s drawings?

It’s interesting how all of their drawings are slightly different in tone and style. Magoso School is putting a lot of work into drawing as emotional self-care. I’ve been told that some of the graduates who have found these sessions really helpful are now supporting them as instructors. That’s why the drawings are all so different. When adults ask children what they’re feeling and give them the opportunity, [the children] gradually open up. And they’ll create all kinds of drawings, maybe because they learn different ways of expressing themselves over time.

Courtesy of MUDEF

What characteristics do you see in the drawings by the Zambian children?

The theme of the drawings is “My Precious Things.” I think the refugee children’s drawings tend to be about people: their mom, their dad, their friends. The children whose families have decided to settle in Zambia tend to draw their houses and cars. Most of the time, when these families are given land, they then have to clear the land and build their houses themselves. I think they must be really proud and happy to finally have a place where they can keep their precious family safe.

: Courtesy of MUDEF

What message would you like to send to the people who see these drawings?

I want to tell them, “Feel what these children are feeling.” I think it’s our feelings that move us. And it would be great if they could also learn about Africa and TICAD in the process. After all, it’s called the Tokyo International Conference. Tokyo is in its name, and the people of Africa recognize it that way, too. I’d like for it to become normal for everyone living in Tokyo to know about the conference.

Courtesy of MUDEF

I suppose the act of drawing is like therapy.

One instructor lost his parents to an infectious disease when he was a child and lived alone, in hiding, in the mountains. He came to Magoso School after being taken into protective custody, but at first he wouldn’t talk very much. He liked to draw, though, and the more time he spent drawing, the more he started to talk.

Art heals the soul. I think that’s why he started teaching drawing, to help these children develop the most important thing you can have as a human being—the power to live.