Many of the giant marsupials and birds that roamed ancient Australia had vanished by 40,000 years ago. While the duration and drivers of these extinctions remain debated, fossils clearly show the continent lost a host of creatures which would have dwarfed humans, such as short-faced kangaroos, diprotodons, “thunder birds” and giant goannas.

Our study published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B suggests these end-Pleistocene extinctions also affected smaller creatures such as lizards. These animals comprise most of biodiversity and biomass.

A bizarre giant among tiny lizards

The most diverse land vertebrates in modern Australia are skinks, which are typically the tiny, nondescript brown lizards that scurry among leaf litter.

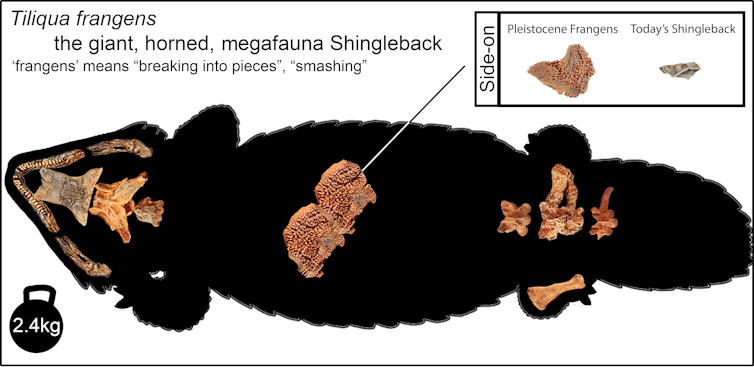

There are some larger and more charismatic forms, such as blue-tongues and shinglebacks (also known as sleepy lizards or bobtails). However, even these are dwarfed by our new fossil skink, Tiliqua frangens (or Frangens), which was more than 60cm long and weighed more than 2kg. This 1,000 times heavier than your typical garden skink.

Frangens was bizarre in many ways: it was covered in very thick, spiky armour and had an extremely wide but blunt skull. Frangens was an enlarged and exaggerated version of its closest living relative, the shingleback, which has these traits but to a much lesser degree.

Katrina Kenny, Author provided

While our large mammalian and avian megafauna are well studied, smaller fossil lizards and snakes are often overlooked. Most of the fossils used to piece together this extinct critter have been sitting in museum collections for decades – some for more than a century.

Read more:

Humans coexisted with three-tonne marsupials and lizards as long as cars in ancient Australia

A jigsaw puzzle with pieces scattered all over Australia

The first two pieces of this creature, a partial lower jaw and skull-roof bone, were found separately in spoil heaps at Wellington Caves, about 200km west of Sydney in 1995 and 2008. These fragments were scientifically described as different species in 2009 and 2012.

Then in 2016, palaeontologists from Flinders University began finding more fossils of a large skink in Cathedral Cave at Wellington Caves. Frangens immediately stood out not just for its unusual size, but for its spikey body armour, abundant in the dig site yet oddly never reported before.

Diana Fusco, Author provided

A study tour of the palaeontology sections of the Australian, South Australian and Melbourne museums brought to light the importance of their collections. Sitting in drawers of unidentified reptiles were near-complete jaws, perfectly preserved braincases, and chunks of fused armour plating from the head of Frangens.

The Queensland Museum had put aside a specimen representing most of a single individual, waiting for someone with the patience and expertise to piece it together.

It became clear the original lower jaw and skull roof, plus all the subsequent material, belonged to a single species.

This wealth of fossils also broadened our understanding of the spatial and temporal range of this highly distinct lizard. Frangens fossils have been recovered from southeastern Queensland through to the northern banks of the Murray River in New South Wales. The fossils range in age from at least 2 million years to 47,000 years old. So Frangens was part of the fauna when the First Peoples arrived.

Author provided

A lost lizard that functioned more like a tortoise?

Australia has never had small land tortoises. Tortoises are completely absent in modern Australia, while the famously large meiolaniid turtles are extinct.

It is possible that in Australia, the heavily armoured, slow-moving Frangens filled the ecological niche that small tortoises occupy on other continents.

Michael Lee, Author provided

Intriguingly, in none of the fossil sites we have explored, do Frangens and the modern shingleback co-occur. Instead, only after Frangens went extinct did shinglebacks expand northward and increase in size: those ranging from the Murray to southeastern Queensland are among Australia’s largest living skinks (reaching up to 1kg).

Nature abhors a vacuum, so these shinglebacks might be growing big to fill the gap left by Frangens, which in turn previously filled the gap caused by the absence of small tortoises.

Furthermore, Frangens was not alone, but was part of a cohort of giant skinks, none of which survived past the end-Pleistocene extinctions.

These fossils show that the extinctions were not confined to “megafauna” – the largest examples of the largest groups. Rather, even some smaller animals such as skinks once had (relatively) large forms, which perished in the late Pleistocene along with giant marsupials and flightless birds.