Collaborations with artists, architects and designers are key to ensuring the longevity of a heritage brand and modernising design classics for a new generation, says Longchamp artistic director Sophie Delafontaine in this interview.

Speaking to Dezeen at the luxury handbag brand’s showroom in London, Delafontaine said that though the push-and-pull of collaboration can prove tricky, it ultimately serves to force a heritage brand like Longchamp to develop outside of its comfort zone.

“It’s our own responsibility as a company to make the best products that we can,” Delafontaine explained. “[We create] iconic products that have a very strong character [and] are very well made, but my role is to push them.”

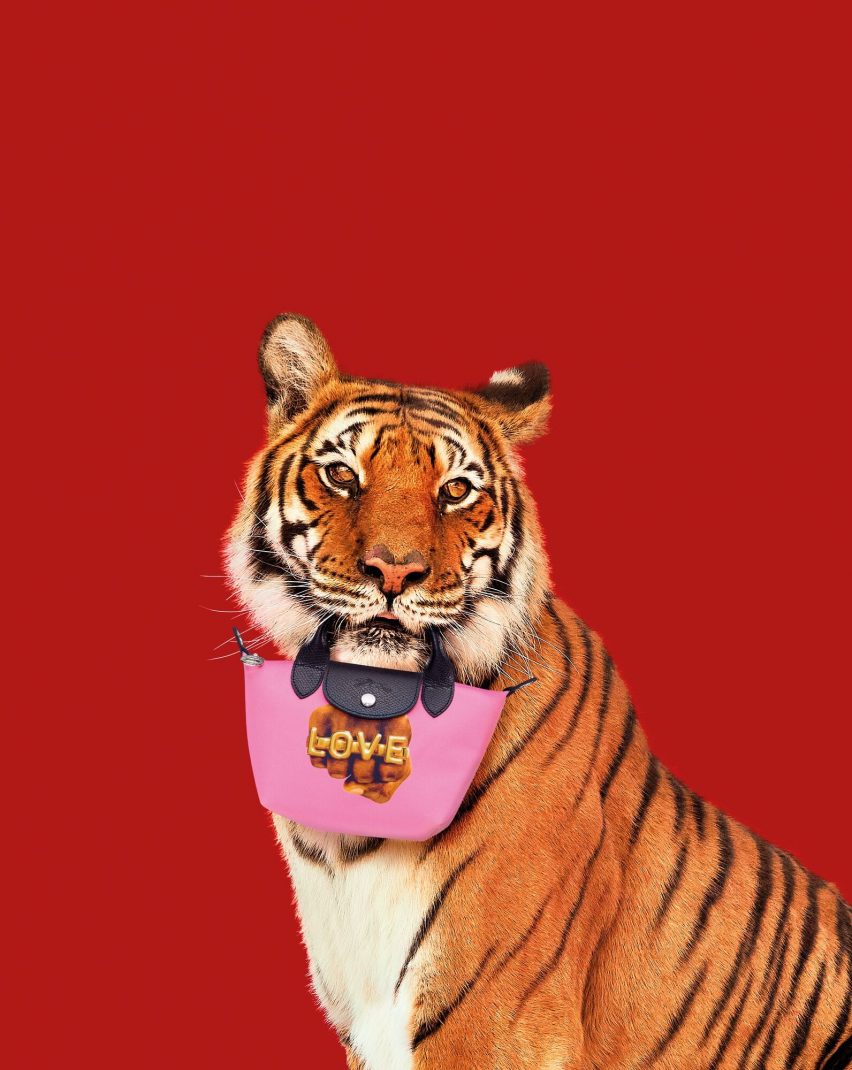

The brand has recently launched a collaboration with Italian art magazine Toiletpaper.

Best known for its origami-informed Le Pliage tote bag, Longchamp was founded by Delafontaine’s grandfather, Jean Cassegrain, as a tobacco and smoking accessories brand in post-war Paris.

“We don’t need the same type of product now that we did 15 years ago”

Delafontaine, who grew up above the brand’s first shop in the city’s 9th arrondissement and previously designed for French luxury childrenswear brand Bonpoint, has been at the helm as artistic director since the early nineties.

She noted that some Longchamp products, like the Roseau leather shoulder bag, have gone through several redesigns over that time in order to keep up with changing trends.

“It’s like Chanel’s number five perfume – the juice has been remade many times. The quality of the material has improved, as well as the shape, detail and proportion.”

“We certainly don’t exactly need the same type of product now that we did 15 years ago because we have everything in our mobile phones and the bags are smaller,” she added.

“It’s hard to collaborate with architects”

Collaborations have become a mainstay of Longchamp during Delafontaine’s tenure, with Turner-nominated artist Tracey Emin, Japanese design firm Nendo, Hood By Air design director Shayne Oliver and British designer Thomas Heatherwick all producing highly-publicised collections for the brand in the past three decades.

The key to managing these collaborations successfully, Delafontaine says, is “to keep the DNA of Longchamp” – in most cases, the structure and design of a Longchamp bag – while introducing “the DNA of the people [the brand] is collaborating with”.

“The idea is for [collaborations] to feel both Longchamp and their universe,” she says. “I don’t like to impose too many restrictions because, for me, the idea is really to catch as much of that creativity as I can.”

“The only restriction is our capability to produce it. It’s always a challenge, but it’s a great challenge for our know-how.”

One such designer who challenged the brand’s ability to produce was Heatherwick, whose 2004 Zip Bag was “very hard” to realise, Delafointaine recalls.

A zip wound in horizontal concentric rings ran the length of the cowhide leather bag, allowing it to expand and contract like an accordion.

“It was really nearly like an architectural bag,” Delafontaine explained, citing the malleability of leather as counterintuitive to Heatherwick’s carefully engineered design.

“And Thomas also has a very precise vision,” she added. “So it was super hard, but we were very happy to be able to make it.”

Though now a rare find on resale sites, the bag that Heatherwick pitched and produced for Longchamp was the beginning of a long-running relationship, which saw the British designer commissioned to design the brand’s global flagship store in Manhattan in 2006.

Now, Delafontaine says, Heatherwick is currently in the process of completing a “very surprising” renovation of the same store.

The Heatherwick collaboration wasn’t Longchamp’s first foray into architecture: the brand tapped French architect Paul Andreu, the lead architect on Paris Charles de Gaulle Airport, to design a bag for its 50th anniversary in the late nineties.

“It’s hard to collaborate with architects,” she admitted. “They are used to doing hard things and I am used to doing soft.”

“So sometimes it’s difficult because their product is going to stay exactly as it is. My products are going to live.”

Toiletpaper is a “very optimistic, playful vision of life”

If architecture is an outlier for Delafontaine, then Longchamp’s latest collaboration with art title Toiletpaper has a richer precedent.

It follows on from collections with Emin – which Delfontaine cites as the brand’s “first major collaboration” – Swedish-French graffiti artist André Saraiva and American-British artist Sarah Morris.

“I think [art] is a way of being creative without constraints, which is not my case as a designer – I create with constraints,” says Delafontaine.

“Of course, I’ve been following Toiletpaper for a very long time. It’s really a very optimistic, playful vision of life, which I really love and which is also something I try to input when creating at Longchamp.”

Founded in 2010 by Italian artist and photographer duo Maurizio Cattelan and Pierpaolo Ferrari, the bi-annual photo magazine is known for highly saturated images that satirise the zeitgeist.

Toiletpaper’s designs for Longchamp’s Le Pliage range feature everything from a French bulldog smoking an archival Longchamp pipe designed by Delafontaine’s grandfather to a flying horse.

Despite its many modern reinventions, Longchamp has retained the same logo for the past 70 years – a jockey on a galloping racehorse that nods to the origin of the brand’s name, which Delafontaine’s grandfather borrowed from the Longchamp Racecourse in Paris.

“I think we have an emblem that is speaking about what Longchamp really is,” says Delafontaine. “He’s a winner.”

Asked why the brand has chosen to keep the same logo, she replied: “Well, because we like it.”

The photography is courtesy of Longchamp.

Dezeen In Depth

If you enjoy reading Dezeen’s interviews, opinions and features, subscribe to Dezeen In Depth. Sent on the last Friday of each month, this newsletter provides a single place to read about the design and architecture stories behind the headlines.