On a recent award-judging panel, I found myself once again in a conversation about what makes a book of poems “cohesive” – that is, what makes it a book-length experience, as distinct from a single-poem dip, a chapbook dive or, indeed, the narrative journey of a novel.

The panel’s consensus was that it is not necessarily theme that holds a collection between two covers. It can be structural features, such as symmetries or contrasts. It can be a dramatic terrain of action and voice. Or it might be an experiment in technique and form that creates a conceptual sandwich.

In David McCooey’s The Book of Falling, much is made of the titular theme as the cohesive element. As well as the title, the book’s blurb, its endorsements and its epigraphs all point to this conceit.

The contents, on the other hand, say something else. In the section and poem titles, and in the poems themselves, we encounter the grand themes of phenomenology and time scales. McCooey circles back repeatedly to “vacant times”: to the separation of humans from other animals, detachments of voice from body, the disintegration of physical matter between past and present.

If I could choose an image to represent this shadow conceit, it would not be falling, but something more horizontal and glitchy.

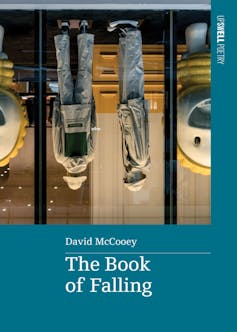

Review: The Book of Falling – David McCooey (Upswell)

The best poems in The Book of Falling, and its most original and purposeful reason, are the three “photo poems” at its centre. I want to focus on these before considering the less compelling poems that flank the heart of the book.

The formal and conceptual gravitas of the photo-poem sequences lies in their variety of media and style, and the unexpected combinations of signification created by the interfacing photographs and texts. It’s not a radical method, but it carries a surrealist sense of possibility that is quite different to the book’s narrative and imagistic poems.

The first series, Posing Cards, features pictures taken by McCooey’s father Wyndham. His archival snaps are themselves poetic in their absurd, Forbesian contradictions: a jocular group, including a fellow wielding a rifle; a man-cave plastered with a sign that says “The Arse End” and a finger pointing to a memento mori.

Accompanying these fun compositions is a sober series of instructions for blocking a family portrait:

Place Mom and Dad

in the standard Mom and Dad sitting pose.Then bring in the children.

The poet lets us do the work of inventing connections between these imperatives and the resistant images, between the tension of son and father, bringing into play McCooey’s established affinity for cinema, and particularly horror.

Redundancies and Bathroom Abstraction use McCooey’s own photographs, which stand in high tonal and stylistic contrast to his father’s raucous eye. The photos are highly mannered images of geometrically framed bathrooms and brutalist architecture, cool and controlled.

In Redundancies, the unpeopled surfaces of reinforced concrete match the robotic language of found poems drawn from corporate mass communiques to employees during the pandemic. You know the sort of thing:

I want to assure you that we

are working hard

to provide as much certainty

to you as possible.

Although McCooey makes no source attribution for these, as a fellow academic I feel confident they are from university communications.

The images and text build a story about a withdrawal of genuine social personality, but to me it seems too easy to satirise these Orwellian placations without having something more to say about them.

Domestic spaces

The series Bathroom Abstraction, on the other hand, is haunted – the poet addresses the subject of the poems in the second person, summoning his alienating experiences of bathrooms like psychological snapshots:

You think about the bathroom you made your way to after your bypass operation. Crossing your hands over your chest and applying pressure, like the nursing staff told you.

These prose poems are more felt, more earnest than those in Redundancies. McCooey is laying more on the line here, referring to the vulnerability of bodies that are naked, ill or attending to their basic needs.

The Book of Falling dwells in the domestic spaces where these sorts of vulnerabilities tend to occur (and to be hidden). Even when not writing about bathrooms, the regular scenes of looking out the windows of home, of bedrooms, of watching television or weather, have a similar quality of privacy and enclosure: “The night-time wind sweeps its baton among the rubbish behind some anonymous buildings.”

This theme is established in Lives I, the opening trio of poems. These dramatise the voices of three famous dead women as they move through imaginary space and time. They round out the palette of The Book of Falling, but they seem an odd choice as an opening sequence. They are much more fully resolved and intricately composed than other poems in the book, which look slight by comparison.

The concept is perhaps a touch gimmicky; I wondered whether Marilyn Monroe, if she were alive in this century as McCooey fantasises, would really only respond to the public reporting of sexual assault by saying: “yes: me too, me too”. But that is the poet’s prerogative.

Adam Aitken: a forensic poet with obsessive resolve

Resonant phrases

McCooey is capable of resonant phrases. He has a penchant for oxymoronic images like “Honey and maggots” or “the brief duration of abysmal sleep”. He is also capable of some clangers:

Meanwhile the bats in the ironbark tree

are taking to the sky. Their breathtaking wings

have an extensive repertoire of sounds.

Why not simply “ironbark” without “tree”? Are the wings themselves “breathtaking” or would that adjective more aptly describe the sound they make? Surely it is the poet’s job to describe the repertoire, not tell us about it (nor describe the sound of actual bats as “bats in a horror movie”).

My taste is for McCooey’s lighter tankas and fragments. I enjoyed their freeness, the sense of the poet simply enjoying himself with a bit of objectivist simplicity and not being too careful about well-wrought anything:

And as if someone uttered the trigger word,

rain begins without ceremony.But it’s not “driving rain”;

it’s just sitting outside,engine idling over the neighbourhood.

It’s neither coming nor going.It doesn’t give a damn.

And then, like a poem ending,you look out the window,

and the rain has stopped,the birds have returned, and the wind

has begun its invisible cover-up job.

Other poems in this mode are lean, rather than being either pregnant with ambiguity or densely glittering. In a full-length collection they run the risk of becoming stocking fillers. A similar hollowness or scrappiness is found in the satires and elegies that comprise a later section of the book; they are neither witty nor dark enough to justify their inclusion. Maybe they just needed to be pushed harder, across the threshold from sweet into the strange places that McCooey reaches in the photo poems.

The final sequence, Lives II, takes an autofictional turn and might have been better as the opening set. As with Bathroom Abstractions, McCooey here drops the performative tone of the satires and the vacant voices of the dramatic characters, and inhabits his own memory more deeply through third-person narration:

The film is finished; the day is over. While his son talks himself to sleep, M sits by a window looking onto the street, the whole world caught in the giant belly of the night.

Reading The Book of Falling, I constantly wanted to go at the poems with a pen to remove final lines and unnecessary punctuation at line ends, smarten up those bats, cut the thin poems. I wanted to restructure the plodding sections in a way that would properly frame the photo poems, intersperse them perhaps, or add more of them, really claim their form as the statement of this book.

As a reader and critic, I school myself to accept a work on its own merits; you can’t fail a book because it doesn’t deliver on your own idea of it. But McCooey is a mature poet and Upswell is a vital publisher; together they could have punched this up into something more robust.