Agatha Christie published The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb in September 1923, almost a year after the discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb in Egypt’s Valley of the Kings. Her Hercule Poirot short story drew inspiration from the sensationalised folklore of the “mummy’s curse”. Lord Carnarvon, sponsor of the excavation, had died on April 5 1923, less than two months after he had entered Tutankhamun’s burial chamber.

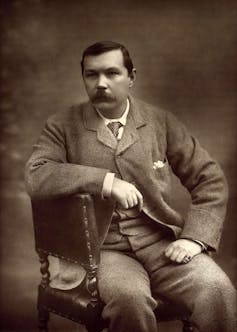

Yet, there was another inspiration for Christie’s story: Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes novel, The Hound of the Baskervilles (1902). Christie draws on Conan Doyle’s novel in the design and unpacking of the alleged curse which, in both stories, actually turns out to be a sophisticated crime

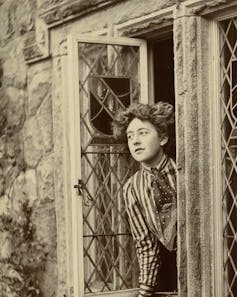

Christie was familiar with Egypt, having stayed for three months in Cairo with her mother in 1910. The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb deliberately references Carnarvon’s death at her story’s outset, channelling “Tutmania” and the alleged curse into her fiction.

Poirot is summoned by Lady Willard, the widow of Sir John Willard, who died shortly after excavating “funereal chambers” near the “Pyramids of Gizeh”. Willard’s death, coupled with the deaths of others on the dig, becomes the talk of the day. As the narrator, Arthur Hastings, observes: “The magic power of dead-and-gone Egypt was exalted to a fetish point.”

While Willard died of heart failure, Poirot reveals that a member of the dig team, Dr Ames, had been exploiting Willard’s death to harness the power of superstition and kill for financial gain. In this regard, and in others, the story mirrors The Hound of the Baskervilles, in which a murderer excavates a family curse as a cover for their crime, in an attempt to acquire Baskerville Hall.

Is Hercule Poirot autistic? Here are seven clues that he might be

The power of superstition

The murderers of both stories rely on superstition to shield them. The Baskerville family live with a curse involving a gigantic hound. It allegedly haunts the family after the evil Sir Hugo Baskerville pursued a woman across the moors to her death. The legend is passed through generations of the Baskerville family.

Sir Hugo’s descendent, Stapleton, who is third in line to the Baskerville estate, deploys the power of the curse. He creates his own demon hound by painting a large dog’s fur with blue luminescent paint and releasing it onto the moors. The sight of what looks like the demon hound kills the owner of Baskerville Hall, Sir Charles. He dies, like Willard in Christie’s story, of heart failure.

Mary Evans/Studiocanal Films/ Alamy Stock Photo

But it is how the detectives respond to superstition which cements the connections between the Conan Doyle and Christie stories. Both sleuths utilise superstition to expose the villains.

In The Hound of the Baskervilles, Holmes warns the new heir, Sir Henry, of the demon legend to keep him off the moor: “Bear in mind, Sir Henry, one of the phrases in that queer old legend … and avoid the moor in those hours of darkness when the powers of evil are exalted.”

Holmes knows, although we do not, that the moor is dangerous for a Baskerville. Not because anything supernatural is afoot, but because the threat comes from a dangerous living animal and its murderous master. When Holmes tricks Stapleton into revealing his hound, the curse is laid to rest.

Similarly, Poirot confirms that he believes “in the terrific force of superstition”. And on the dig site he has a trustworthy member of the team disguise himself as Anubis, “the jackal-headed, the god of departing souls”, to bring the case to a crisis point and unveil the villain.

Why Tutankhamun’s curse continues to fascinate, 100 years after his discovery

Conan Doyle’s “elementals” and Christie’s archaeology

In the first publication of his story, Conan Doyle noted that he “owed its inception” to Bertram Fletcher Robinson. The journalist had told him about an evil Devonshire squire, Richard Cabell, who died in 1677. His ghost, surrounded by fiendish hounds, was reputedly seen on the moors.

Bonham’s

Around the same time, Robinson was researching the misfortunes that befell those who handled an ancient Egyptian artefact known as the “unlucky mummy” but that was actually a wooden board used to cover a mummy and painted to look like the person when they were alive. He died shortly afterwards.

Christie’s The Adventure of the Egyptian Tomb also refers to the “unlucky mummy”, saying it was “dragged out with fresh zest” when Willard died after entering the tomb of “King Men-her-Ra”. Even today, the British Museum confirms that the object has a “reputation for bringing misfortune”, though it explains that this has no “basis in fact”.

Conan Doyle reported to the press that an “evil element” might have caused Carnavon’s “fatal illness” and connected his death with Robinson’s. Conan Doyle observed: “One does not know what elementals existed in those days, nor what their form might be.”

The Christie Archive Trust

Christie’s story demonstrates her engagement with Conan Doyle’s writing, as well as her interest in Egypt. A decade later she became an amateur archaeologist, supporting the digs of her archaeologist husband, Max Mallowan, in the Middle East.

Christie’s story also taps into the global interest in Tutankhamun. By the early 1920s, Conan Doyle – though still publishing Sherlock Holmes stories – was coming to the end of his career, while Christie’s was just beginning.

In the final decade of his life, Conan Doyle embraced spiritualism, a religious movement that proclaimed the dead could communicate with the living. This opened him to the idea of ancient curses. He was, in the words of Sherlock Holmes in The Hound of the Baskervilles, inclined to “supernatural explanation”.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.