Colleen McClain, Olivia Sidoti and Monica Anderson contributed to this chapter.

For many Americans, life in the early days of COVID-19 was lived on screens. Schools pivoted to virtual learning and businesses shuttered or moved online as in-person contact risked spreading the virus.

Not everyone could – or wanted to – avoid in-person interaction. And some did not have the resources or skills to navigate this technological shift. But for others, relying more on technology was the “new normal.”

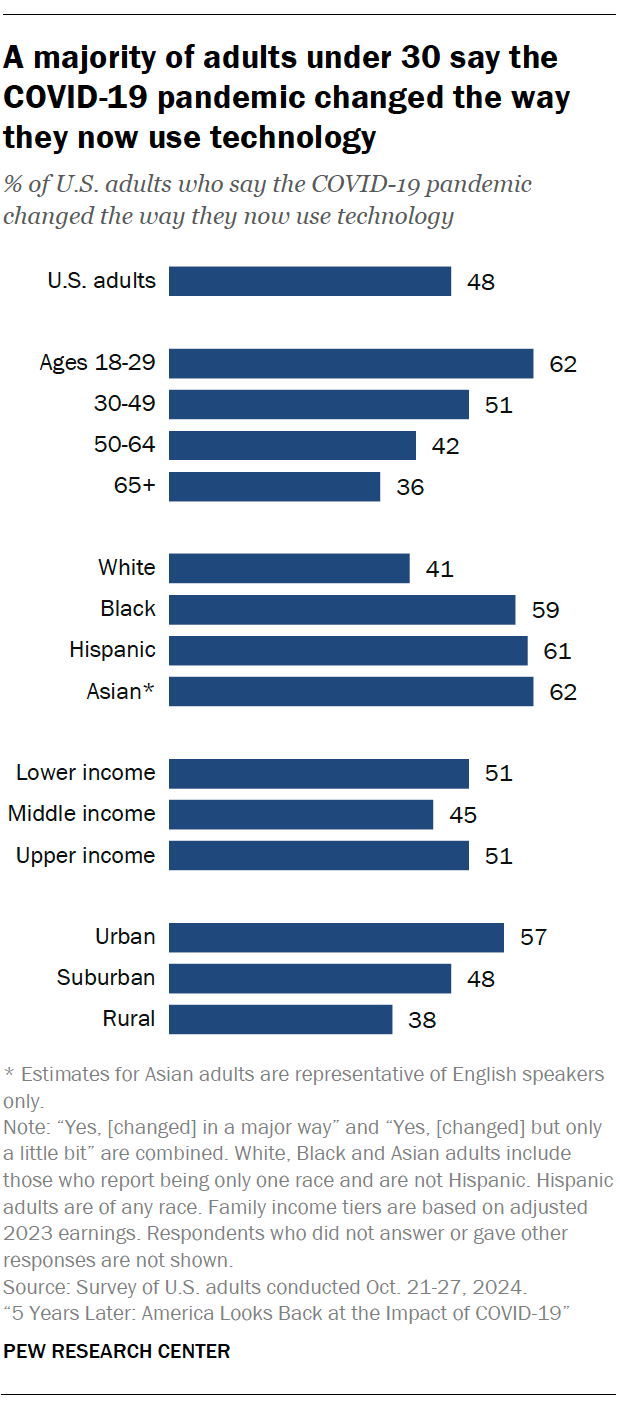

Some of these changes are still with us: 48% of Americans say the COVID-19 pandemic changed the way they now use technology, according to a Pew Research Center survey conducted in October 2024.

This includes 18% who say the pandemic changed their current technology use in a major way.

Like Americans’ pandemic experiences, these changes – and their impacts – are far from one-size-fits-all.

By age

Younger adults stand out – 62% of adults under 30 say the pandemic changed how they now use technology. Still, some older adults say this too:

- 51% of those ages 30 to 49

- 42% of those 50 to 64

- 36% of those 65 and older

By race and ethnicity

About six-in-ten Black, Hispanic and Asian Americans say their technology use is different now due to the pandemic. This compares with about four-in-ten White adults.

Urban adults are most likely to say their technology use is now different, followed by their suburban counterparts. Rural Americans are least likely to say this.

By household income

There are only modest differences by income. About half of those in lower-income and upper-income households say the pandemic changed their technology use. A slightly smaller share of those in middle-income households say this.

How changing technology use impacted Americans’ lives

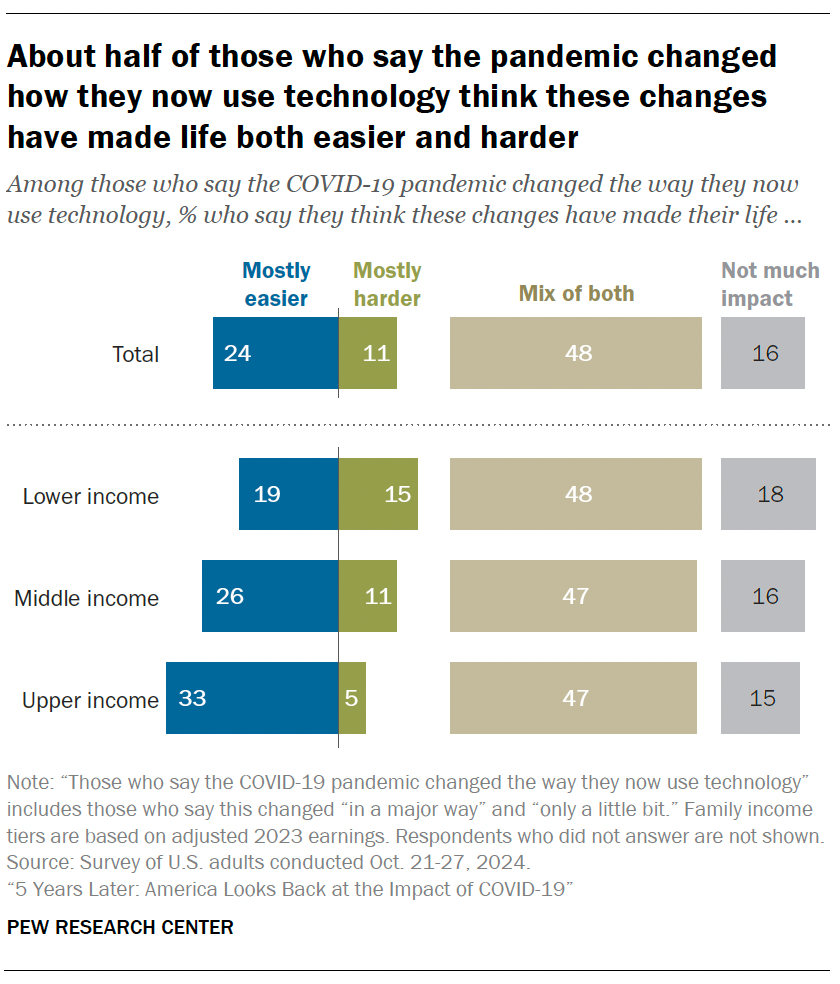

Asked how these changes have impacted their lives now, people report a mix of good and bad.

Among those who say COVID-19 changed the way they now use technology:

- 48% say these changes made their life a mix of both easier and harder

- 24% say they’ve made life mostly easier

- 11% say they’ve made life mostly harder

- 16% say they haven’t had much impact either way

By household income

Those living in upper-income households are most likely to say that these changes have made their life easier. People in lower-income households, by comparison, are most likely to report hardship – though relatively few in each income group say this.

The largest shares across income levels say these changes have had mixed effects – that is, they’ve made life both easier and harder.

By age

Among those who report change, adults ages 65 and older (29%) are more likely than those 50 to 64 (16%) or under 50 (13%) to say these changes didn’t have much impact on them.

Looking back over the pandemic

Our findings reflect the complex – and sometimes challenging – realities of how Americans used technology as the pandemic unfolded. In the sections below, we walk through some of what we’ve learned over the past five years.

Jump to read about the role of the internet in Americans’ lives during the pandemic: The importance of the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic

Jump to read about the digital divides the pandemic shone a spotlight on, including: Affordability | Digital literacy

Jump to read about key stories of tech and daily life during the pandemic: Virtual learning | The “homework gap” | Screen time | Virtual connections and “Zoom fatigue” | Tech and relationships

The importance of the internet during the COVID-19 pandemic

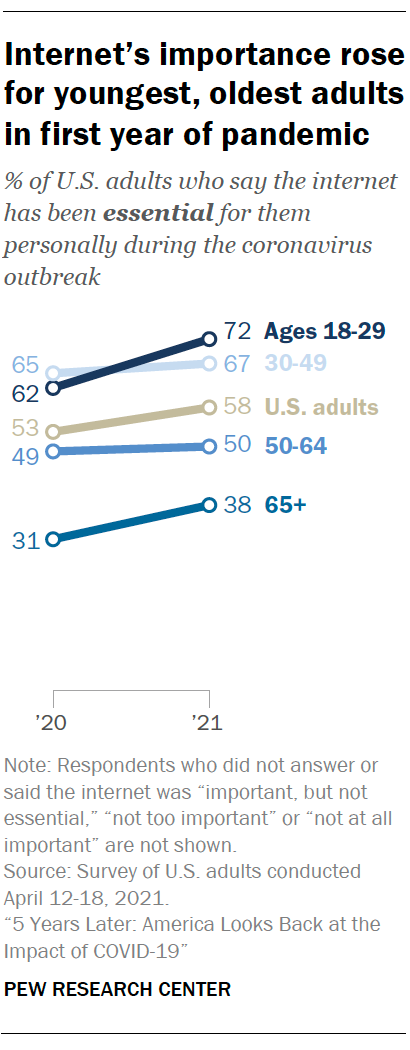

As many daily activities shifted online, Americans’ reliance on the internet ticked up over the first year of the pandemic. By April 2021, 58% of Americans said it had been essential to them during the outbreak, up slightly from 53% a year prior.

The share saying the internet was essential rose for younger and older adults alike. The share of adults under 30 saying it was essential rose from 62% to 72%. Among those 65 and older, it rose from 31% to 38%.

The shares of Americans ages 30 to 64 who said the internet had been essential remained stable over that same period.

All told, 90% of Americans acknowledged at least some importance of the internet in their lives at the pandemic’s one-year mark. (That includes 33% who said it was important, but not essential.)

Digital divides and the pandemic

Not everyone faced this shift with the same resources and skills. COVID-19 thrust long-standing digital divides into the spotlight, from gaps in internet access by age and income to struggles with reliable connections.

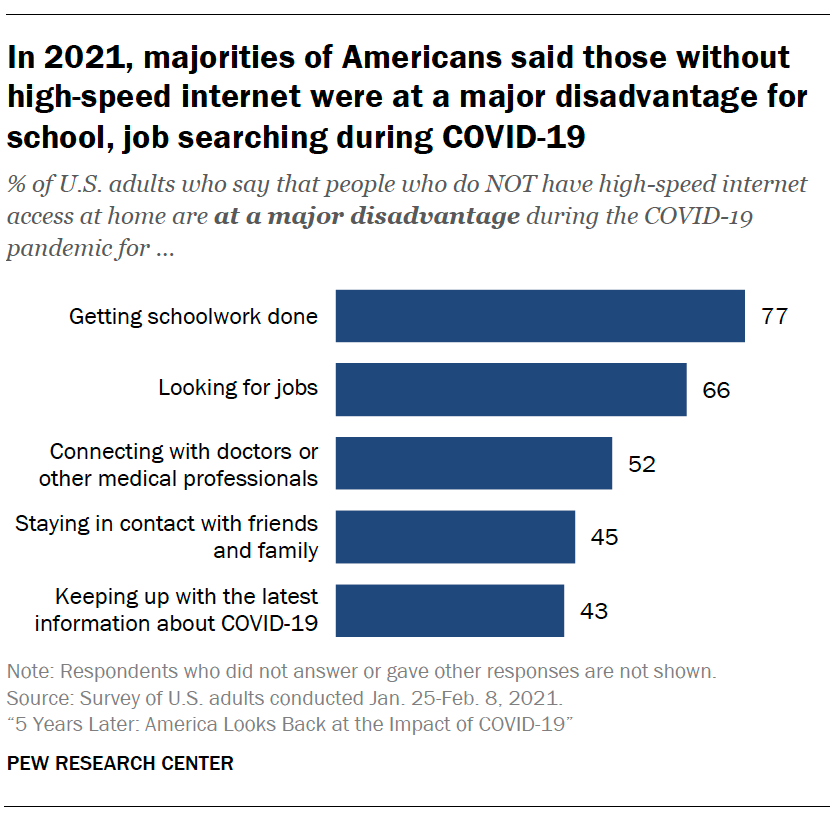

Americans saw clear disadvantages for those without internet access during the pandemic.

In 2021, majorities of Americans said those who didn’t have high-speed internet were at a major disadvantage for schoolwork and job searching. About half said the same about getting medical care.

Even for those with access, the pandemic thrust issues of affordability and digital literacy into the spotlight. Some groups were more likely to struggle in these areas than others.

Affordability

Broadband costs have long been an issue for some Americans and are among the main reasons people don’t subscribe.

As the pandemic hit Americans’ pocketbooks, subscribers struggled with costs too. About three-in-ten U.S. home broadband subscribers were at least somewhat worried about being able to pay their internet bills in our April 2020 survey.

By household income

Lower-income households were hit especially hard: 52% of home broadband subscribers with lower incomes said in April 2020 they worried at least some about paying their internet bills over the next few months. And as the pandemic continued, the government stepped in to help people pay.

Today, affordability remains a concern as inflation looms large. Our fall 2024 survey shows 34% of broadband subscribers worry a lot or some about paying their internet bills. By income, this is:

- 56% of subscribers in lower-income households

- 31% in middle-income households

- 12% in upper-income households

Digital literacy

One of the major narratives from the pandemic centered around whether Americans – especially older Americans – had the digital skills they needed to face a technology-focused reality. From registering for vaccine appointments to ordering food online, everyday tasks suddenly required tech “savviness.”

Our work found that a year into the pandemic in April 2021, 10% of adults said they had little to no confidence using computers, smartphones or other electronic devices to do what they needed to do online. And 26% said they usually needed help setting up new devices or learning how to use them.

By age

Older Americans were far more likely to struggle in these ways. In 2021, 24% of Americans 75 and older said they had little to no confidence in their digital skills, and 66% usually needed help with new devices.

Differences by age persist today. For example, 65% of those 75 and older say they usually need help with device setup, according to the October survey. This compares with smaller shares of adults ages 65 to 74 (48%), 50 to 64 (25%) and under 50 (9%).

Technology and daily life during COVID-19

Even as digital divides played out, the “new normal” some Americans were thrust into extended across areas like school, socializing and work. A year into the pandemic, four-in-ten Americans overall told us they had used technology in new ways (though a larger share hadn’t done this).

Below, we look back on some of the biggest stories about how Americans were using – and sometimes struggling with – technology during this time.

Virtual learning

As schools closed and assignments went virtual, concern that the pandemic would hurt test scores and widen achievement gaps drew widespread attention.

And two years into the pandemic, we found a majority of teens (ages 13 to 17) said they’d prefer in-person schooling post-pandemic, versus online or hybrid learning. Teens also had mixed feelings about how virtual learning was going. About three-in-ten teens (28%) said they were extremely or very satisfied with how their schools had handled it, but a similar share (30%) reported being only a little or not at all satisfied.

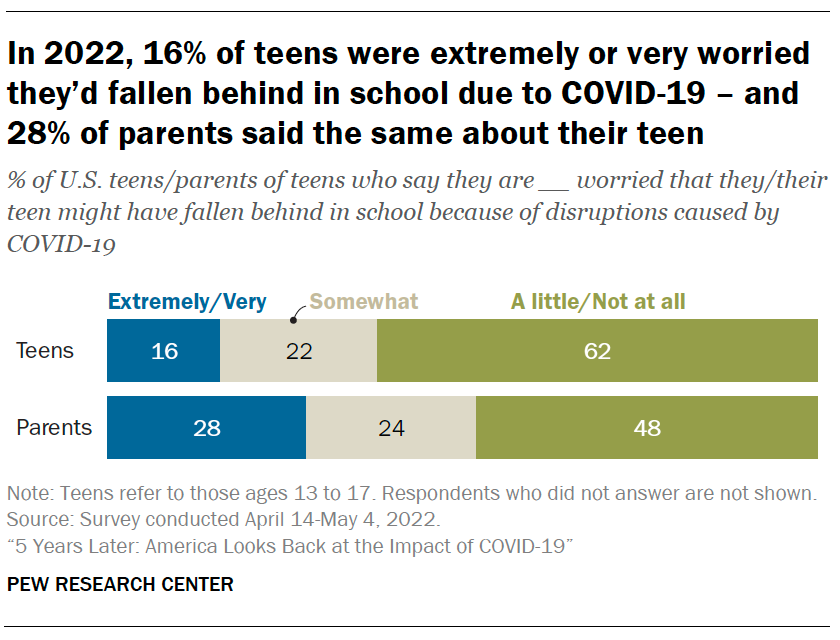

At the same time, we found 16% of teens were extremely or very worried they’d fallen behind in school due to pandemic-related disruptions.

A larger share of parents of teens (28%) were highly worried that their teen was falling behind in school due to these disruptions. But this varied by income: 44% of parents whose annual household income was less than $30,000 said they were extremely or very worried, compared with 24% of those living in households earning $75,000 or more a year.

Parents also had mixed feelings about how virtual learning was going overall, though their views were slightly more positive than teens’.

The ‘homework gap’

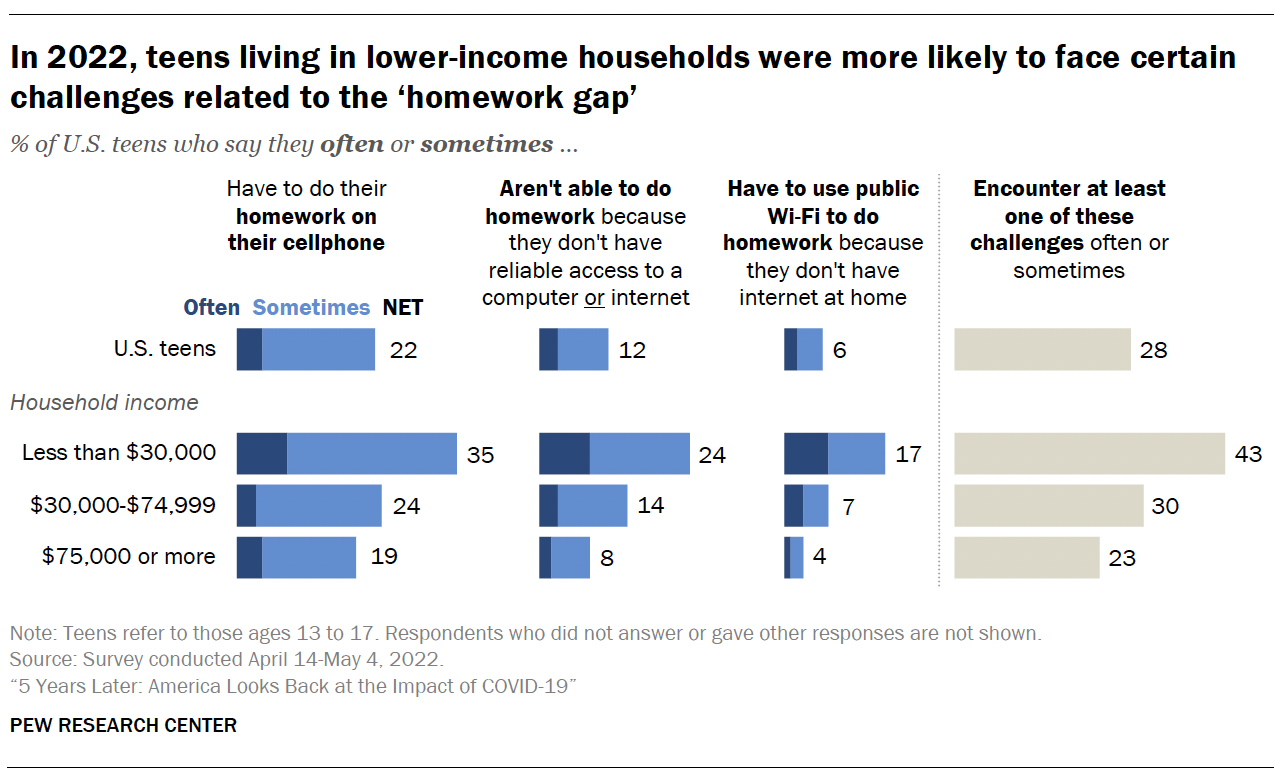

The same survey found that teens in lower-income households were especially likely to face technology-related barriers to getting schoolwork done – often called the “homework gap.”

One of these was having to do homework on a cellphone. About one-in-five teens said in 2022 they often or sometimes had to do so, and lower-income teens stood out:

- 35% of teens in households making less than $30,000 annually said they at least sometimes had to use a cellphone for homework.

- 24% of teens in households making $30,000 to $74,999 said this.

- 19% of teens in households making $75,000 or more said the same.

About a quarter of teens in lower-income households said they at least sometimes couldn’t complete homework because they lacked reliable access to a computer or the internet. That’s higher than the shares of teens in higher-income households reporting the same. And there’s a similar pattern in using public Wi-Fi to do homework.

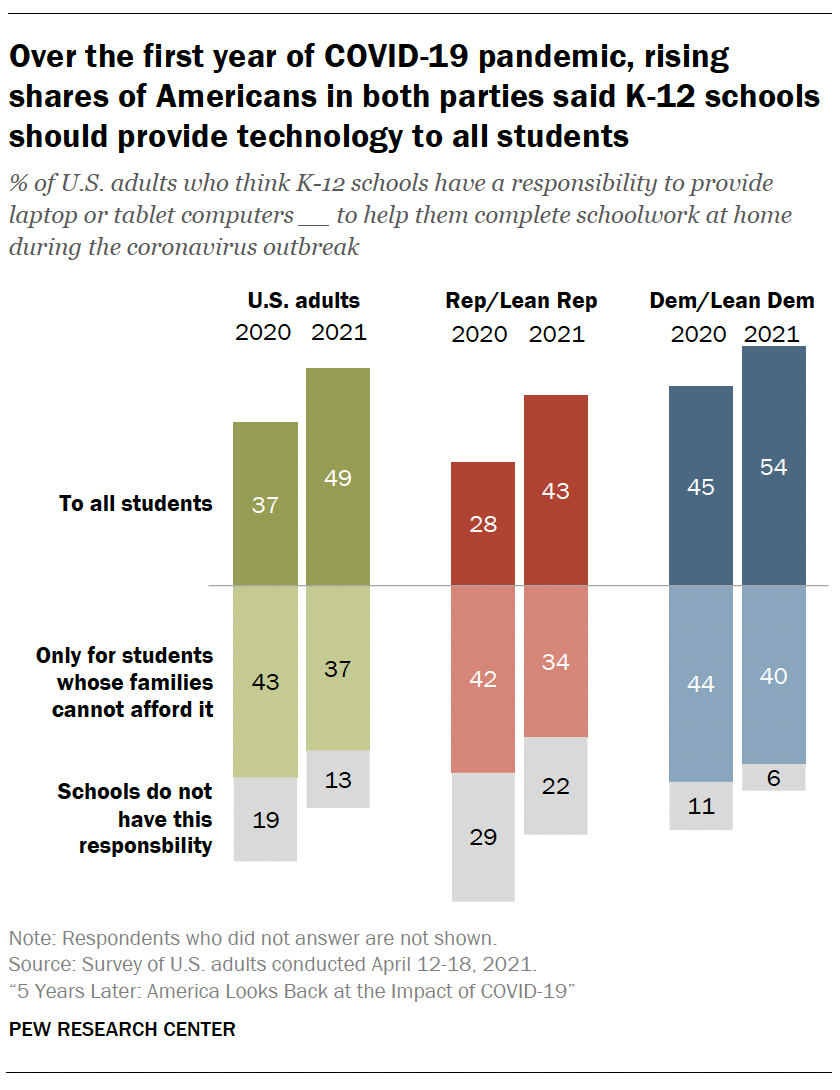

Amid struggles like these, schools scrambled to get technology in the hands of students.

The share of Americans saying K-12 schools should provide technology to all students during the outbreak rose over the first year of the pandemic:

- From 37% to 49% among all adults

- From 28% to 43% among Republicans and GOP-leaning independents

- From 45% to 54% among Democrats and leaners

At the same time, some called on the federal government to do more to address the digital divide.

And we saw the share of Americans saying the federal government had a responsibility to provide access to high-speed internet to all Americans rise from 28% in 2019 to 43% in 2021, according to a separate 2021 Center study. By comparison, the other views of government responsibility we measured changed little over the same period.

Screen time

In addition to understanding the virtual learning environment, we also tackled a modern conundrum for many parents: screen time.

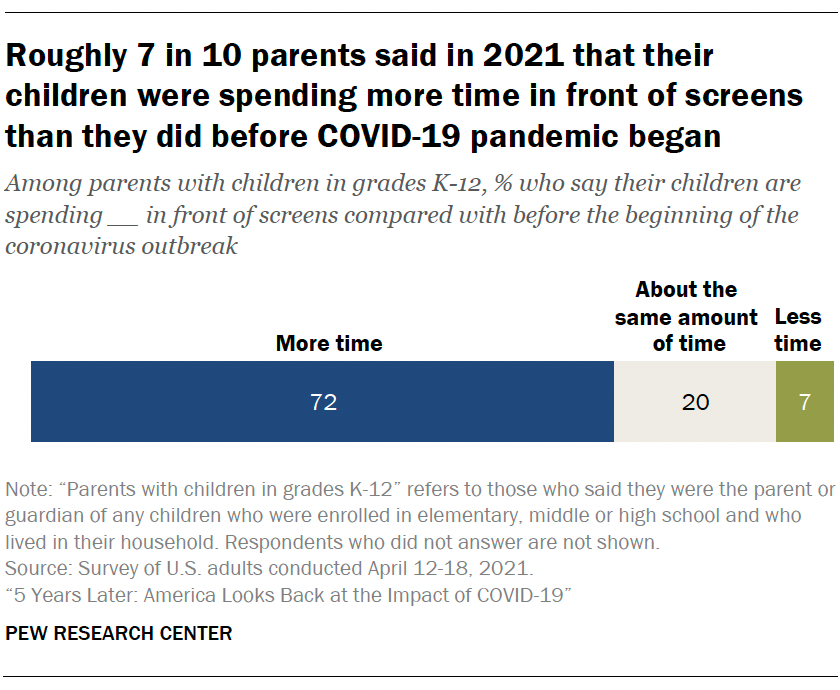

In April 2021, most parents reported their kids’ screen time was on the rise. Overall, 72% of K-12 parents said their child was spending more time in front of screens than before the outbreak. Smaller shares said their child’s screen time was about the same as before (20%) or was less than before the pandemic (7%).

Asked about screen time aside from schoolwork, parents were also more likely to say they softened their rules than to say they became stricter.

- 39% of K-12 parents said they become less strict about their child’s screen time since the beginning of the pandemic.

- 18% became more strict.

- Another 43% said things had stayed about the same.

Today, screen time is still top-of-mind for many parents. And our 2023 and 2024 surveys show teens are as digitally connected as ever.

Virtual connections and ‘Zoom fatigue’

People were finding virtual ways to connect in the early days of the outbreak. Overall, 32% of adults said they had a virtual party or social gathering with friends or family due to the outbreak, according to an April 2020 survey. For adults under 30, that figure rose to roughly half.

From personal calls to remote work, video calls became a mainstay of some Americans’ lives. One year into the pandemic, 81% of U.S. adults said they had talked with others via video calls at some point since it began. This included one-in-five who said they did this daily.

But these calls did have a downside to some users, popularly coined “Zoom fatigue.” Four-in-ten of those who had used video calling in the first year of the pandemic felt worn out from such calls at least sometimes.

Tech and relationships

Behind the video calls and virtual parties was a lingering question: What was all this doing to our relationships?

Many Americans thought connecting via technology left something to be desired. Our March 2020 survey found that a majority thought meeting online or over the phone couldn’t fully substitute for meeting face-to-face.

That was still true when we surveyed Americans again about a year later. About two-thirds (68%) felt that virtual interactions had been useful, but not a replacement for in person contact. In contrast, 17% said that these interactions had been as good as in-person and another 15% said they were not of much use.

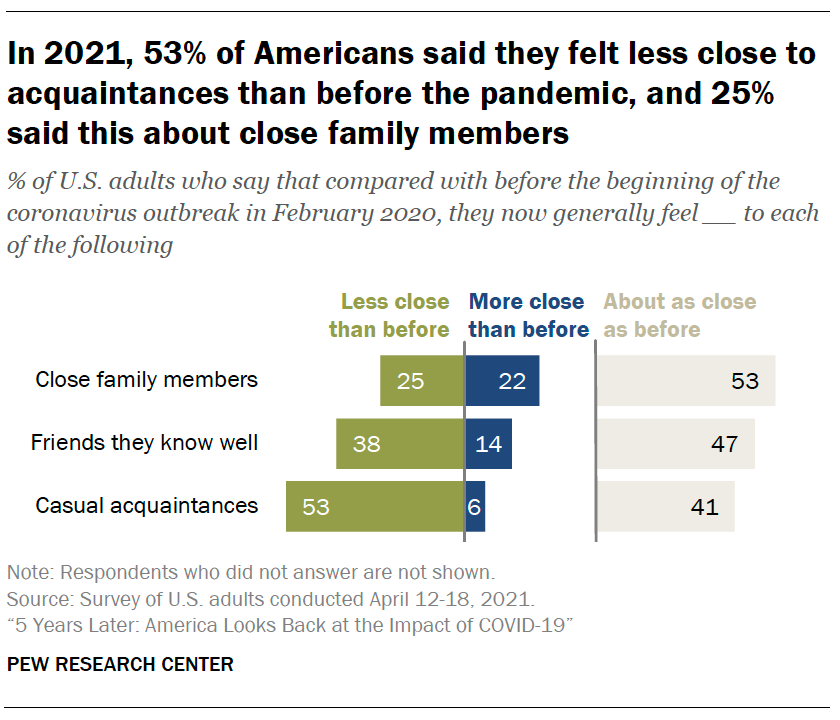

For some, the closeness of relationships changed over this first year. But how this played out depended on the relationship in question.

About half of U.S. adults said they felt less close with casual acquaintances. Roughly four-in-ten said the same about friends they know well. And a quarter said this about close family members.

Still, some said relationships grew closer. For example, 22% said they felt closer to family than before the pandemic.

But for close friends and family alike, the largest shares of Americans said these relationships had stayed about the same.