For several years, in France and elsewhere, higher education has been questioned about its role and responsibilities in the current socio-environmental crises. In response, numerous research projects and initiatives have emerged to better integrate the principles and goals of sustainable development into the various curricula, particularly since the Higher Education for Sustainable Development Initiative (HESI) was launched on the sidelines of the United Nations Rio+20 Conference.

However, although these issues are increasingly being addressed in specific courses or sessions on ethics or sustainable development, awareness-raising activities such as the Climate Fresk or assessment tests such as the Sulitest, pressure is mounting on higher education institutions, particularly in engineering and management.

The Student Manifesto for an ecological awakening launched in 2018, or the recent calls among engineers and business students to branch out or rebel show that, despite certain efforts, young people feel that the curricula continue to perpetuate the dominant model that has led to the current and future complex crises.

It must be recognised that this integrative approach – adding a course or a session when the already full curriculum allows it – remains contradictory and creates confusion by disseminating paradoxical injunctions between unchanged courses and new pedagogical activities, without training in how to manage these contradictions.

We should therefore go beyond this, by engaging the curricula in a transformative approach. No longer integrate sustainable development into engineering or management education, but rather teach engineering and management for sustainable development. It is by transforming the programs in depth that each student will have the knowledge and skills necessary to be responsible and committed actors in the transitions to come, both personally and professionally.

Which skills to integrate?

Faced with this observation, the world of higher education seems to be in turmoil and excitement. How can curricula be transformed? Should we deconstruct everything? What skills should be integrated? In France, recent large-scale initiatives are tackling these questions, such as the working group chaired by Jean Jouzel, whose report was submitted to the government in February 2022, or the Shift Project and their ClimatSup Business project.

Although these initiatives provide a solid basis for reflection and action, general reflection is still too often focused on identifying key competencies for sustainable development without sufficiently addressing other fundamental issues.

Indeed, the skills are already known. Academic literature (e.g., Redman and Wiek (2021), Moosmayer et al. (2020) or Lozano and Barreiro-Gen (2021)) as well as international reports, including those of the European Union, Unesco or the OECD, have been converging for several years on a clear set of competencies.

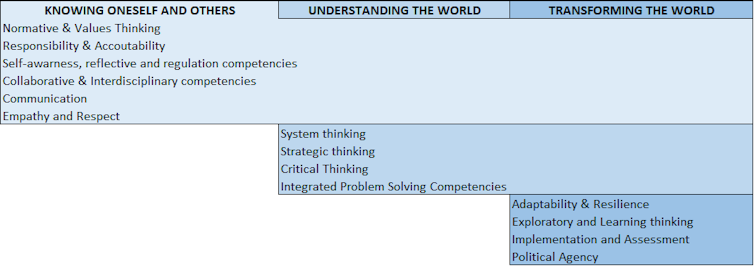

Through our research and institutional activities, we have been able to produce a comprehensive framework of 13 skills integrating these different sources:

Fourni par l’auteur

Together, they represent a pathway structured in three progressively overlapping blocks:

This framework is not discipline-specific and is intended to support students, faculty, programme managers, higher education institution governors and policy-makers in their efforts to transform the curriculum.

The transition will take time

While the identification of these competencies over the past few years has not been easy, the hardest part may be yet to come. Their respective definitions are still unclear, and their operationalisation is even more so.

What exactly do these competencies mean for engineering and management? What degree of autonomy should students achieve in each of them? How can they be translated into specific learning objectives? What should be the learning situations to achieve them? What are the assessment situations for this learning?

Institutional initiatives, such as at Pennsylvania State University or international initiatives, such as PRME’s i5 project or EFMD’s training program, are emerging to address these issues. But they remain complex and developing the answers and implementing them on a large scale will take time.

Competitive pressures, particularly in France, limit the capacity of institutions to fully engage in this evolution. Above all, this pressure limits collective thinking, whereas it is through collaboration, within and between disciplines, that new models of higher education can be developed and deployed.

In addition to institutional collaborations, these reflections must not remain only a process of experts and policy-makers. In particular, it is essential that students, and young people in general, are fully integrated into these transitions. For example, at the start of the 2022 academic year at SKEMA Business School, nearly 800 students in the first year of the Grande École programme were invited to participate in a week-long Hackathon on Higher Education in Transition, with the aim of integrating their work into the institution’s transition.

In addition, in October 2022, the World Youth Observatory was launched with a first massive collective intelligence consultation: Youth Talks. Supported by a set of more than 30 international partnerships with higher education institutions and youth groups, the objective of this international initiative is to reach more than 200 million young people between 15 and 29 years old around the world in order to collect the aspirations of at least 150,000 of them.

The necessary transition of higher education models requires a real paradigm shift, based not only on new skills, but also on a profound transformation of the narratives, values, metaphors and symbols that explicitly or implicitly structure the current models.

It is only through these changes that we will finally be able to develop new common horizons and move toward so-called humanistic models of education in management or engineering that would privilege human dignity and collective well-being, rather than wealth, power or status.