Think about Halloween, and romance is unlikely to be the first thing that comes to mind. But Victorian periodicals and newspapers show that alongside dressing in costumes, enjoying themed cuisine and telling ghost stories, historical Halloween food traditions were often centred on love. Here are three examples you can try for yourself.

Halloween nuts

An article published in the London magazine Kind Words for Boys and Girls in 1889 describes the autumnal traditions that marked this time of year throughout history. One particularly popular snack they point to is hazelnuts and cobnuts, which were in plentiful supply in the autumn.

Brighton & Hove Museums

Rather than being part of a snack or game, however, the author notes that they were the “arbiters of fate” – a fate that was romantic. Those curious about the future of their love-life would place a nut on the grate of a brightly burning fire, and name it after their sweetheart. The status of their romance was divined through the way the nut burned. A short story published in Every Boy’s Magazine in 1896 also refers to this tradition.

In the story, the narrator describes a Halloween visit to Scotland. Having read Robert Burns’s poem, Halloween, the narrator describes being at a gathering where sweethearts “burnt nuts and watched their fate with anxious hearts”. Should the nuts remain on the grate and roast peacefully side by side, the chances of harmonious love were good. If the nuts darted off and sparked out the fire erratically, the relationship was doomed.

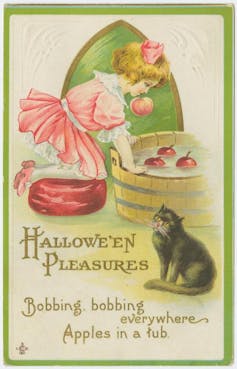

Roasting nuts and bobbing for apples are depicted in this story as traditions that “had died out in England”, but were “preserved in full vigour in Ireland and Scotland”. These Celtic associations with Halloween traditions are emphasised in another article.

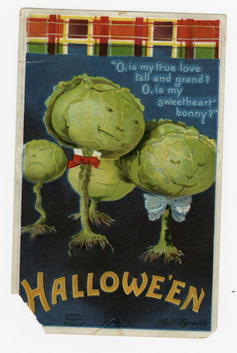

Halloween kale

In 1879 in a children’s magazine called Little Wide-Awake, the Scottish author George Cupples (1822-1891) wrote an entry on October traditions called Talks About the Months. Alongside the nuts and apples which Cupples writes are “consumed in immense numbers” across the United Kingdom, he describes other peculiar ceremonies including another type of food: kale.

William H. Hannon Library

As with the romantic cobnuts, this kale is not for eating – at least in the first instance – and its significance is again tied to love.

“In some places there is the pulling of ‘kale-storks’, or stalks of calewort”, writes Cupples, “to see if one’s future husband is to be tall or straight, little or crooked”. The root of the kale apparently represented the stature of one’s future spouse. Not only that, but the amount of dirt that clung to the stalk indicated the wealth of a future partner, and “if the pith tastes sweet it shows that the husband or wife of the lucky individual is to be sweet also”.

The Halloween party games Cupples describes are similarly centred on love. The Three Dishes game consisted of three basins: one filled with clean water, one with dirty water and one left empty. A blindfolded player is sent forward to dip their fingers into one and decide their romantic fate.

If they touch the clean water, a happy marriage to a young man or maiden awaits. If they chance upon the foul water, they are set to marry a widow or widower and if they choose the empty dish “the person is destined to be a bachelor or an old maid”.

Soul cakes

These activities may have been followed with “souling” on All Soul’s Day, November 2. Souling, a longstanding tradition with links to Christianity rather than paganism, is comparable to trick-or-treating in that it involved going from door-to-door to beg for “soul cakes”.

Flickr/New York Public Library

These are oaten cakes, sometimes containing seeds, fruits, or nuts, as well as spices, and were either round or triangular in shape. A recipe for soul cakes from a 1604 manuscript recipe book reads as follows:

Take flower & sugar & nutmeg & cloves & mace & sweet butter & sack & a little ale barme, beat your spice, & put in your butter & your sack, cold, then work it well all together, & make it in little cakes, & so bake them, if you will you may put in some saffron into them and fruit.

When “souling”, these cakes would be handed out as people sung a rhyme: “Soul, soul, for a soul-cake; Pray you, good mistress, a soul cake.”

Food was therefore tied into multiple Halloween traditions that often had love trouble at their core, leaning into the idea that spirits could shed light on mysteries, including future romance. But what also shines through, is that 19th-century authors frequently associated Halloween with other, distant, time periods.

Whether traditions were framed as the simple, “rough” ways of countryside or Celtic folks, tied to outdated religious practices, or simply viewed as folkloric fun, Victorian authors repeatedly described the celebration of Halloween in terms that evoked a darker, spookier, more unknowable past.

Looking for something good? Cut through the noise with a carefully curated selection of the latest releases, live events and exhibitions, straight to your inbox every fortnight, on Fridays. Sign up here.