No photos of the war. No photos of its victims. No mention of the hundreds of photographers who have died taking them. We are a group of activists and artists who believe the future will be shaped by those who can see it. We stand together against the forces that refuse to let us. The future is being shaped by art festivals that choose what we see. Hiding behind the pretty face of diversity, while refusing to see the genocide.

This arresting public statement accompanies a series of large-scale street posters called no-photo2024. The anonymous artists and activists behind no-photo2024 are highlighting the exclusion of Palestinian photographers from the PHOTO 2024 festival, now showing in Melbourne.

The no-photo2024 posters are strategically placed near PHOTO 2024 venues. Their aim is to highlight the contradiction of excluding the atrocities captured by Palestinian photographers in Gaza.

Australian media’s Instagram posts on Gaza war have an anti-Palestine bias. That has real-world consequences

PHOTO 2024

Although the organisation behind PHOTO 2024, Photo Australia, calls itself “apolitical”, the festival has built its reputation by promoting and commissioning politically charged works by First Nations, African, Middle Eastern and LGBTQI+ photographers. Big names from previous festivals include Hoda Afshar, Christian Thompson, Paul Mpagi Sepuya, Hayley Millar Baker, Broomberg and Chanarin, Mohamed Bourouissa and Aziz Hazara.

The festival commissions new work for outdoor projects and through an open call process invites submissions from artists and photographers worldwide. Applications are assessed by an international jury of leading photography and visual art curators. The festival also stages public programs and incorporates satellite events and exhibitions in collaboration with cultural, education, industry and regional partners.

The festival is well known for setting themes that promote photography’s role in challenging power. PHOTO 2021 explored the theme of “the truth” at the height of Donald Trump’s presidency, attracting projects focused on the reliability of photography in social media, fake news and AI. The program that year boasted supporting “First Nations truth-telling” and “the experience of whistleblowers who have spoken out for those whose voices were never meant to be heard”.

This year, the festival continues to promote socio-political issues with the theme “the future is shaped by those who can see it”. Events include an ideas summit exploring photography as activism, among other timely discussions. The hero image by Morroccan-Belgian photographer Mous Lamrabat presents two African models adorned in fashionable garments which read “stop terrorising our world”.

But there are no photographs from Palestinian photographers.

The Conversation approached PHOTO 2024 for comment. They said:

Over 150 artists are exhibiting at PHOTO 2024 International Festival of Photography, selected in response to a curatorial theme set in 2022. PHOTO Australia did not exclude any artists due to race, religion, nationality, age, disability, sexual orientation, gender identity or any other personal characteristics. PHOTO Australia stands by its values to create an inclusive platform that doesn’t discriminate, censor nor diminish the plethora of expressions artists bring to the world. Artists exhibited by PHOTO Australia were invited directly, or applied to our open call in February 2023 and were selected in consultation with local and international curators.

The majority of the program is presented by 40 cultural institutions and independent galleries who curated their own exhibitions in response to the theme, and selected artists according to their own curatorial policies.

The contract of photography

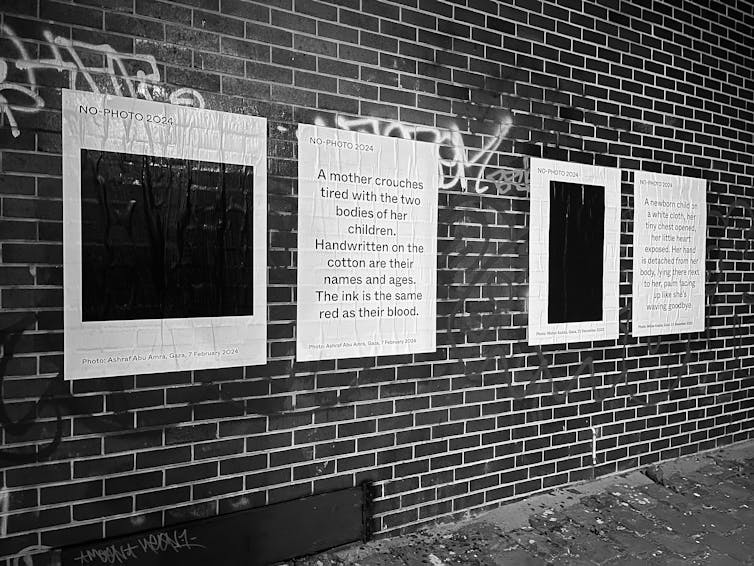

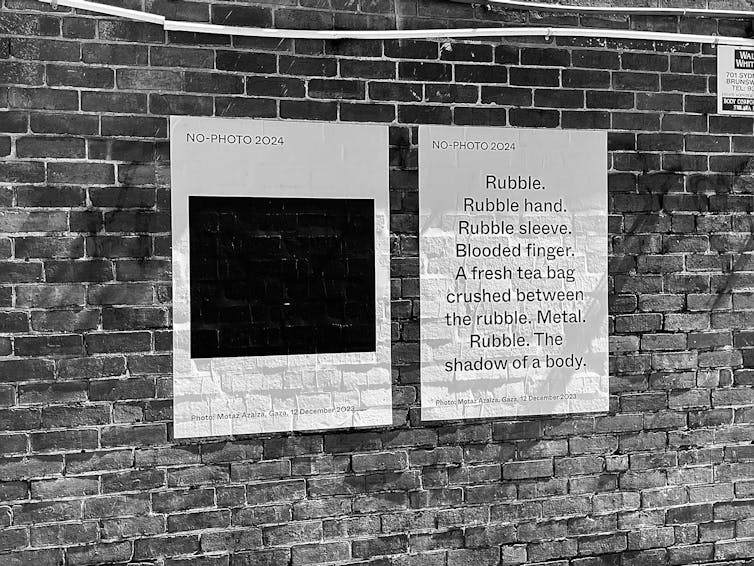

The no-photo2024 posters present a black square or rectangle symbolising a redacted photograph. Adjacent descriptive text reveals the hidden narrative of the censored image. Every poster is printed with a caption attributing the text description and the redacted image to a Palestinian photographer.

The juxtaposition of the redacted image and the textual description not only commemorates the efforts of Palestinian photographers but also prompts a broader reflection on the societal and ethical implications of selectively withholding images of atrocity from the public eye.

no-photo2024

The posters expertly draw on the influential work of Israeli writer Ariella Azoulay and the outspoken Jewish-American theorist Judith Butler.

Azoulay’s The Civil Contract of Photography (2008) explores photography’s political and ethical conditions, proposing it as a social practice linked to citizenship, human rights and sovereignty – not just an art form.

She introduces the idea of a “civil contract” where photography acts as an agreement of mutuality and responsibility between the photographer, subject and the viewer.

no-photo2024

Azoulay suggests photography can build solidarity. She argues photographs are a form of testimony, bearing witness to injustices and human rights violations. Significantly, she uses Palestine as a critical example of how photography can document the realities of occupation, conflict and resistance.

Azoulay challenges the age-old idea that photographs are simply past moments. She instead views them as active engagements that invite ethical and political participation. In no-photo2024 we have a precise example of putting Azoulay’s theory into practice.

The posters also draw on Judith Butler’s Precarious Life (2004) and Frames of War: When Is Life Grievable? (2009).

Butler asserts the media’s portrayal of individuals through photography, crafts a narrative that privileges some lives over others. They argue the media dictates who we mourn and who we overlook.

no-photo2024

This disparity results from deliberate choices in how images are framed based on politics and race. Hence, they write, our connection (or indifference) to the suffering of others through images is often manipulated, leading to “desensitisation” to the plight of those deemed “other” or less human, an argument first formulated in Susan Sontag’s equally influential Regarding the Pain of Others (2003).

Butler dissects how the media’s selective framing of the “other” (Palestinians, in the case of no-photo2024) not only obscures the true impact of violence and war but actively shapes our perception of who deserves to be mourned. Butler views photography’s dual role in perpetuating indifference and promoting a radical shift in our ethical orientation toward action.

Our shared, precarious world

no-photo2024 is a powerful call to action. It prompts collective reflection on how images hold the potential to bear witness to atrocities, mobilise public opinion, and contribute to the struggle for human rights and social justice.

One poster reads, “Rubble. Rubble hand. Rubble sleeve. Blooded finger. A fresh tea bag crushed between the rubble. Metal. Rubble. The shadow of a body”. The Instagram post documenting the paired poster states it is “installed near a commercial art gallery that demands silence on Palestine from its artists, fearing a loss of support from their patrons.”

no-photo2024

In this post-photographic AI-driven age, no-photo2024 promotes a much needed conversation about the ethical responsibilities of creating, curating and consuming photographs. It challenges the photographic community to move beyond aesthetic appreciation and engage with images as participants in a shared, precarious world.

Australian writers festivals are engulfed in controversy over the war in Gaza. How can they uphold their duty to public debate?