When it comes to the natural elements, wind’s role in shaping our world can be overlooked. The worship of the sun in ancient cultures such as Egypt is common knowledge, and ancient gods such as the Roman Vulcan deify volcanoes and fire.

But the work of wind – invisible to the naked eye – often goes unnoticed. Yet, for millennia, this unseen force has critically shaped aspects of life as varied as religion, trade, warfare, culture, science and more.

Mysterious and magical, wind has been worshipped, decided the outcome of innumerable military battles and powered the processes of scientific exploration.

Wikimedia Commons

Wind and the natural world

Wind can be described simply as the movement of air from areas of high to low pressure. By definition, wind maintains a perpetual motion. Wind is a critical element for the maintenance of life on Earth – while the sun provides the planet with warmth, wind disperses this solar energy, allowing for a habitable biosphere.

As well as shaping the course of human history, wind has shaped the Earth and its contents. A powerful terraforming force, it is as influential as glaciers and rivers in moulding landmasses and creating mountains. Far from earth, winds blowing through the cosmos are thought to seed the formation of galaxies, while in the Southern Ocean, westerly winds feed the movement of the world’s strongest ocean current.

British Antarctic Survey/AP

Wind has influenced the growth of plants and the evolution of their physical forms, and has at times wielded an unseen evolutionary force over animals.

A recent study of neotropic lizards (tree-dwelling reptiles) found lizards with bigger toepads were more common in areas that experience frequent hurricane activity. Larger feet appeared better able to cling to points of security during powerful winds. Similarly, hurricane activity is thought to be shaping the evolution of some species of spiders, making them more aggressive.

Wind spreads the seeds, spores and pollens necessary for fertilising the planet. It also carries life-giving rains, at times through aerial pathways known as “flying rivers”.

Yet, the damaging potential of wind is as costly as it is unpredictable. In 2022, the Atlantic storm known as Hurricane Ian took 161 lives and caused over US$100 billion dollars in damage. Hurricane Katrina, in 2005, caused catastrophic flooding, widespread damage and the loss of over 1,800 lives. The financial cost of Katrina has been estimated at over US$125 billion.

How the costs of disasters like Hurricane Ian are calculated – and why it takes so long to add them up

Wind and religion

Wind’s unseen force has been recognised since the times of our earliest written records. In literature from ancient Mesopotamia (an area roughly synonymous with modern-day Iraq), a theme appears that continues throughout much later literature — the fusion of wind and religion in human thought.

World History Encylopedia

Enlil is a primary deity in the Mesopotamian pantheon, situated at the top of the divine hierarchy from the earliest times. Described as “king” or “supreme lord”, his name can be translated as “Lord Wind”. Enlil’s wife is named Ninlil, meaning “Lady Wind”.

Enlil at times wields wind as a weapon. In the Epic of Gilgamesh, he sends a great storm to destroy most of humanity. Wind is also weaponised in the Babylonian Creation myth, Enuma Elish, which dates to around 1200 BCE. In this myth, a cosmic battle involves an array of savage winds, alongside the divine creation of the cardinal winds, North, South, East and West.

Guide to the classics: the Epic of Gilgamesh

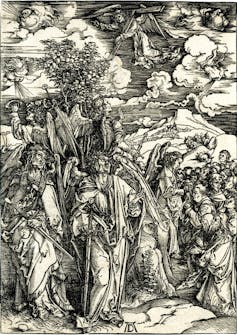

In the Bible, the cardinal winds are frequently connected to apocalyptic settings. The four winds are involved in mediating the power of life and death in the Books of Job, Matthew, Mark, and Ezekiel, while under the power of God or angels (or both).

Wikimedia Commons

The connection between the cardinal winds and apocalypse is reflected in art. The German Renaissance artist, Albrecht Dürer, depicts angels holding the four winds in his work The Apocalypse with Pictures (1498). It represents a passage from the Book of Revelation, where angels are described “holding back” the four winds, thus representing the staying of divine judgement prior to further cataclysmic events.

In Egyptian religion, the four cardinal winds are found in the Pyramid texts – sacred texts carved on the walls of the pyramids of Egyptian rulers during the Old Kingdom period.

In these texts, the four winds were viewed as servants of the Egyptian god of creation and the sun, Ra. The four winds were thought to stand behind him. Their power of “looking with two faces” meant their gaze could either be protective or harmful.

In the Egyptian Coffin Texts, the cardinal winds were connected to the afterlife. They also played a complex role in ancient Egyptian magic. Wind and magic have long been fused in religious thought. In many ancient cultures, religious practitioners were believed capable of magically summoning the wind and manipulating its power.

Fertile breezes

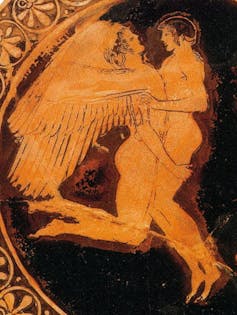

As well as recognising the wind’s dangerous and destructive potential, ancient cultures revered its creative capacity. In Greek myth, unions between wind and plant deities, such as Chloris the flower goddess and Zephyrus, the West-Wind, mirrored the role of the wind in spreading seeds and pollinating plants.

World History Encyclopedia

It was thought at this time that wind’s fertilising role worked on animals, too. Several early works in the genre of natural history, such as Pliny the Elder’s The Natural History (c. 1st century CE), describe divine, animate winds impregnating mares. The Roman poet Virgil described this behaviour as inspired by the Roman love goddess, Venus.

In myths from West Africa and South America, wind shows a religious association with breath, as well as living and ancestral spirits.

The wind deity Oya is connected to tornadoes, change and rebirth. These connections symbolically represent the role of wind in bringing rains and assisting in the production of new life.

Winds of war

The invisible force of wind has helped shape the course of innumerable human battles. An ancient example of the use of wind in warfare comes from the Battle of Cannae. In 216 BCE, Hannibal, the famous Carthaginian general, led his troops to victory over the larger Roman army in a bloody battle that took place in south-eastern Italy.

Wikimedia Commons

Hannibal understood the direction of a scorching local wind, known as the libeccio, could prove a decisive element in the battle.

Knowing the wind would intensify in the heat of the afternoon, Hannibal positioned his troops so it would blow against their backs – and into the faces of his enemies. Hannibal’s success was recorded by the Roman historian, Livy. The hot wind blew dust and grit into the eyes of the Romans, obstructing their vision.

During the English War of the Roses (1455-1487), the wind helped the Yorkists defeat the Lancastrians in the Battle of Towton. While the Lancastrians had claimed the higher ground on the battlefield, the Yorkists had the wind at their backs. This powerful headwind sent their arrows deep into the bodies of the Lancastrians, while limiting the range of their opponents’ arrows.

Sudden changes in the wind were decisive during several points of the 16th century battles of the Spanish Armada. Fortuitous winds also played a key role helping George Washington escape a British siege in the Battle of Long Island during the American Revolutionary War (1775-83).

Washington’s retreat was assisted by the arrival of a fog and a wind shift that filled the sails of his company’s ships. In a later battle, a tornado pressed the British troops into retreat.

Wikimedia Commons

More contemporary examples show how wind can be a fickle friend on the battlefield. During the first world war, the use of chlorine, mustard and other gases led to both psychological horror and devastating death and injuries.

Wind speeds and direction were carefully measured by military meteorologists, who advised on the optimal time to release gas to cause the greatest damage to the opposing side.

Wikimedia Commons

But a change in the wind’s direction, or a shift in its intensity, could result in unintended consequences – and potentially, blowback. The nebulous quality of gas borne on wind meant the poisons could not be restricted to the battlefield, easily carrying to villages near the battlefront. This caused civilian deaths, too.

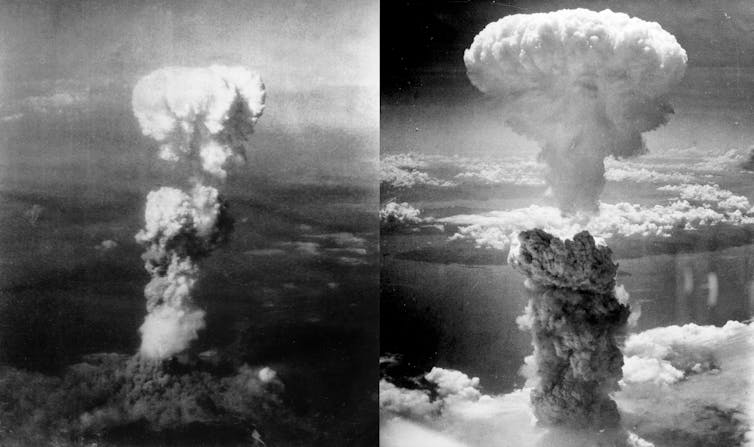

Nuclear fallout

In modern times, the unpredictability of wind has influenced the testing and use of nuclear weapons. On August 6, 1945, crosswinds meant the nuclear bomb dropped over Hiroshima was carried a short distance from its aiming point – the Aioi Bridge – to the Shima Hospital, which was instantly destroyed.

Wikimedia Commons

In 1954, the testing of nuclear fusion bombs on the Bikini Atoll by the US military was adversely affected by an unexpected weather event. The wind on the first of March in Bikini did not follow the predicted patterns of the meteorologists. Strong westerly winds carried fallout contamination across the population of the Marshall Islands, and beyond.

More than 70 years later, Bikini Islanders continue to face the consequences of the spread of radiation from the nuclear tests. Wind shear and ocean currents carried the fallout from the tests as far as Europe, Australia and India.

AP

Shaping technology

The invisible potency of wind has also powerfully shaped the development of technology. Since the Upper Palaeolithic times, wind-born aerofoils have been used for many purposes including hunting. The first known boomerang dates to around 23,000 years ago.

5 Indigenous engineering feats you should know about

Wind filled the sails of early boats in Mesopotamia over 6,000 years ago, allowing for longer sea voyages, trade and cultural exchanges.

And in China, as well as parts of the Middle East, the invention of windmills allowed communities to pump water, grind grain and irrigate crops hundreds of years before the industrial revolution.

In modern times, wind-powered kites featured in many early weather experiments. Wind was critical to the discovery and development of electrical power — perhaps most famously in the experiments of the American polymath, Benjamin Franklin, who flew a kite fastened to a Leyden jar into a thunderstorm to research the connection of lightning to electricity (please don’t try this at home).

Wikimedia Commons

Wind power generated a record amount of electricity in 2022, becoming the top energy producer in the UK. Further from home, the use of wind turbines on the volcanic highlands and crater rims of Mars has been posited as potentially powering future human bases on the red planet.

Last year, wind dispersal was explored as a means for carrying battery-free, wireless-sensing devices (sometimes called “smart dust”) in a study published in Nature.

The authors were inspired by dandelion seeds, which carry adaptions to make them easier to carry on the breeze. Battery-free wireless sensory devices are a relatively new field of research with many potential applications — including the areas of medicine, agriculture and military science.

In the 21st century, the need to understand and appreciate the natural world has become increasingly clear. Wind by its very nature is always shifting, and in recent years, changes to global wind patterns have occurred due to climate change .

Cyclone Ilsa just broke an Australian wind speed record. An expert explains why the science behind this is so complex

Indeed, climate change has been linked to an increase in catastrophic wind-related weather events, an increase in clear air turbulence (also known as “in-flight bumpiness”) and a global reduction in wind speeds known as “The Stilling.”

The impact of climate change on wind is a developing area of study, with the long-term impacts difficult to predict. Delving into the intangible and unpredictable world of the wind is an encounter with nature’s ephemeral complexity.

Louise M. Pryke is the author of Wind, the latest volume in Reaktion’s Earth Series. Wind explores the element’s natural history as well as its cultural life in myth, science, religion, art, music and literature.

_Correction: in the original version of the article, The Book of Revelation was incorrectly listed as the Book of Revelations. _