Violence is a perennial feature of elections in Nigeria. It happens across the three stages of the electoral cycle – before, on and after election day.

The pre-election violence occurs mostly during party primaries – when political parties elect their candidates – and during campaigns.

It’s estimated that more than 1,149 people, including Independent National Electoral Commission employees and security officers, were killed in the three elections held in 2011, 2015 and 2019.

In the past, violence was perpetrated by thugs hired by desperate politicians. But the rise of non-state armed groups and the proliferation of weapons in Nigeria have made election security management even more complex.

Our recent analysis of Nigeria’s 2023 election confirms that the actions of these armed groups are already affecting core elements of election security. There have been abductions involving the electoral commission’s staff and attacks on its offices and sensitive equipment.

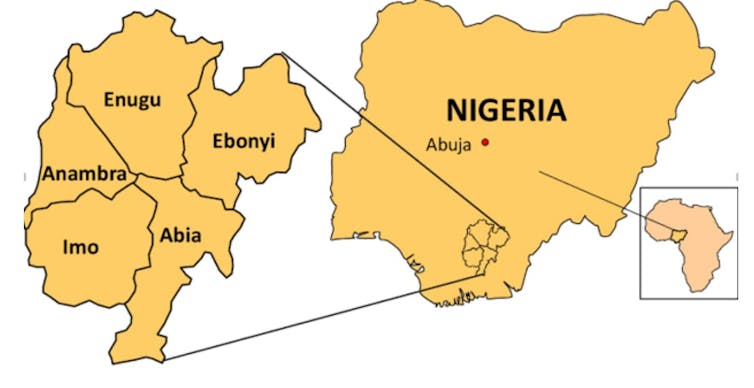

The frequency and intensity of attacks on election security have been most prominent in Nigeria’s south-east zone. The zone consists of five states – Ebonyi, Enugu, Abia, Anambra and Imo – and has 11.49 million voters out of a population of about 22 million.

Our recently published paper identifies the evolving trend of attacks on electoral materials and election commission officials in the south-east region of Nigeria and the implications of this for the success of the 2023 presidential election in Nigeria.

Actors and enablers of violence

In recent years, INEC offices in Nigeria’s south east have been the target of violent attacks by armed groups. At least 134 incidents involving INEC offices and staff have been recorded between 2019 and 2022.

The attacks didn’t happen in a vacuum. Rather, they are situated in a complex web of violent attacks orchestrated by multiple non-state armed groups in the zone.

These include cult groups, Indigenous People of Biafra, communal militia, political thugs, pastoralists, and the criminals widely described as “unknown gunmen” in Nigeria.

The activities of these groups continue to rise amid repressive state responses.

Added to this is the danger that politicians desperate to gain an edge in the election will politicise and even incentivise the violence.

Security agencies heap the violence at the feet of Indigenous People of Biafra. It is almost convenient for state officials to attribute these attacks to IPOB, given that its members were allegedly responsible for much of the attacks on government establishment before the latest decent into widespread violence in the region.

However, a nuanced understanding of the drivers and dynamics of violence in the region may be more useful as a basis for action.

Rising incidents of violent attack

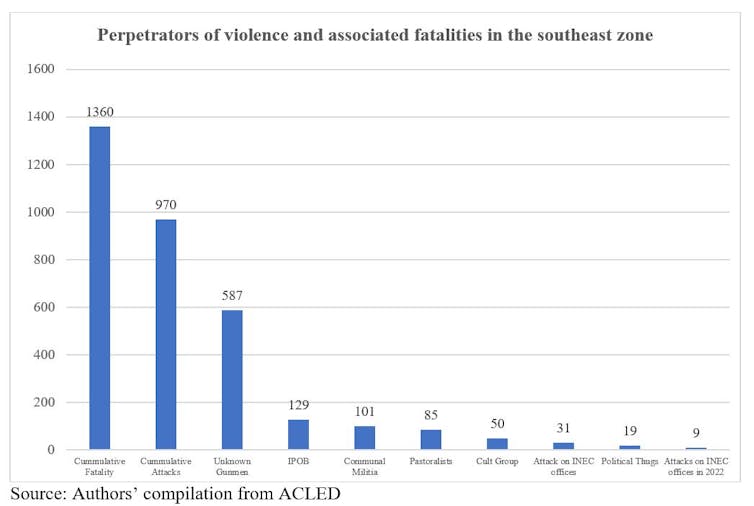

Data from the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data repository, covering general violence, shows that 970 incidents were reported between 2019 and 6 January 2023. An estimated 1,360 were reportedly killed.

The data relies on local groups and media reports. Many incidents probably go unrecorded.

About 60% of these attacks were carried out by unknown gunmen. For its part the Indigenous People of Biafra carried out 129 attacks and communal militia 101. About 31 attacks have been carried out on the electoral commission’s offices in the zone since 2019. Nearly 30% were recorded in 2022.

An example of a recent incident was the attack by an armed group on the electoral commission’s headquarters in Owerri Municipality, Imo state on 12 December 2022. Five people, two of whom were policemen, died.

The state governor claimed that desperate politicians in the state were behind the attack. The Imo state command of the Nigeria Police Force attributed the incidents to Indigenous People of Biafra and its militant wing, the Eastern Security Network.

The incident marked the third attack on the electoral commission’s facilities in Imo State in two weeks following the earlier attacks on its offices in Orlu and Oru West.

Unknown gunmen also attacked the commission’s office in Enugu South Local Government Area, and killed one police officer on 15 January 2023.

Gunmen recently beheaded the sole administrator of Ideato North Local Government Area of Imo state.

The rise, scale and dimensions of violent attacks on members of opposition parties, security agents, electoral commission personnel and infrastructure raise additional concerns about the possibility of a free and fair election in the south-east states.

This has significant implications for the zone, political parties, aspirants and the nation at large.

For the zone, the immediate consequences are being felt in social and economic ramifications. For instance, insecurity and sit-at-home protests in the south-east have led to massive economic losses estimated at almost N4 trillion (US$8.7 billion) in two years.

Implications for the elections

The increasing attacks could render the election less free and fair. Violence risks undermining the electoral process in a number of ways, as we argued in a previous article.

Firstly, the violence could lead to shortages of electoral officials. Secondly, logistics could be compromised, endangering the supply of electoral materials.

Thirdly, voters could be scared away by violence on election days. Presidential candidates might then struggle to get the votes that the constitution requires.

Section 134 of Nigeria’s constitution states that a presidential candidate must secure the highest number of votes cast at the election. He or she must get at least a quarter of the votes cast in each of at least two-thirds of all the states in the Federation and the Federal Capital Territory.

If candidates were unable to meet the constitutional requirements, there might have to be a rerun. That would increase the cost of election in a nation battling with lower revenue and mounting debt.

The electoral prospects of the presidential candidate of the Labour Party, Peter Obi, who is from the south-east region, would be the worst hit by a very low voter turnout. He has been projected to win Nigeria’s 2023 presidential election, according to a poll conducted in December 2022.

In one of the pre-election polls, he led with 68% in the south-east, 46% in the neighbouring south-south.

If the government and state security forces don’t curb the violence in the south-east, Obi’s performance at the poll could suffer.

Way forward

The state security and intelligence outfits need to neutralise violent non-state actors and youth militias of politicians and political parties to prevent them from creating incentives for violence.

This requires timely conduct of threat assessment, profiling of criminal elements or political thugs, proactive deployment for visible policing, and strategic communication to counter violent incentives and narratives.

Greater collaboration between government and communities is also needed to enhance security through President Generals of Town Unions, which are very influential community based associations in Nigeria’s southeast region.