Designer Eleonora Ortolani has created what she believes to be the first food made from plastic waste, as part of her final-year project at Central Saint Martins.

A student of the design school’s masters in Material Futures, Ortolani worked with scientists to take a small amount of plastic, break it down in a lab and turn it into vanillin, the flavour molecule in vanilla.

She then made the vanillin into the foodstuff she most associated with the taste: ice-cream.

The idea for the work, titled Guilty Flavours, came from Ortolani’s frustration with seeing how designers currently use recycled plastic. She saw it often being made into products that couldn’t be recycled any further, because the plastic had been melted with resin or other materials.

“We’re actually making it worse by selling these pieces as a solution for the plastic problem,” Ortolani told Dezeen.

At the same time, she was thinking about wax worms and the bacteria ideonella sakaiensis.

Wax worms typically feed on beeswax but had recently been found to be capable of digesting plastic bags in the same way, and ideonella sakaiensis, discovered outside a bottle-recycling plant in Japan, is thought to have evolved to metabolise PET plastic.

It led Ortolani to wonder, is there any way humans could eat plastic and eliminate it for good? Originally, she thought her project would be purely speculative.

“I would have never imagined that I would actually be able to make food from plastic,” she said. “And it was difficult for me to find a scientist to actually be interested in working with me on that.”

But eventually she found London Metropolitan University food science course leader Hamid Ghoddusi, and through him research scientist Joanna Sadler, whose team at the University of Edinburgh used genetically engineered bacteria to synthesise vanillin from plastic.

Synthetic vanillin is already commonly sold and consumed in supermarkets as a cheaper alternative to natural vanilla.

This synthetic vanillin is usually produced from crude oil, sharing the same fossil fuel origin as plastic, which is partly what drew the scientists to choose the flavour molecule for their experiment.

Ortolani explained that the scientists engineered an enzyme that they placed in E. coli bacteria to enable it to sever the super-strong links between molecules in the structure of plastic as part of its metabolic process. Another enzyme then synthesised these unlinked molecules into vanillin.

“In the moment where the first enzymes break the chain, it’s not plastic anymore,” said Ortolani. “It’s not a polymer anymore. It’s monomers. It’s elements.”

The product of this process should not be confused with microplastics, which are still plastic on a molecular level.

“Microplastic looks like it’s a molecule, but it’s actually a very tiny bit of plastic,” said Ortolani. “It’s not broken.”

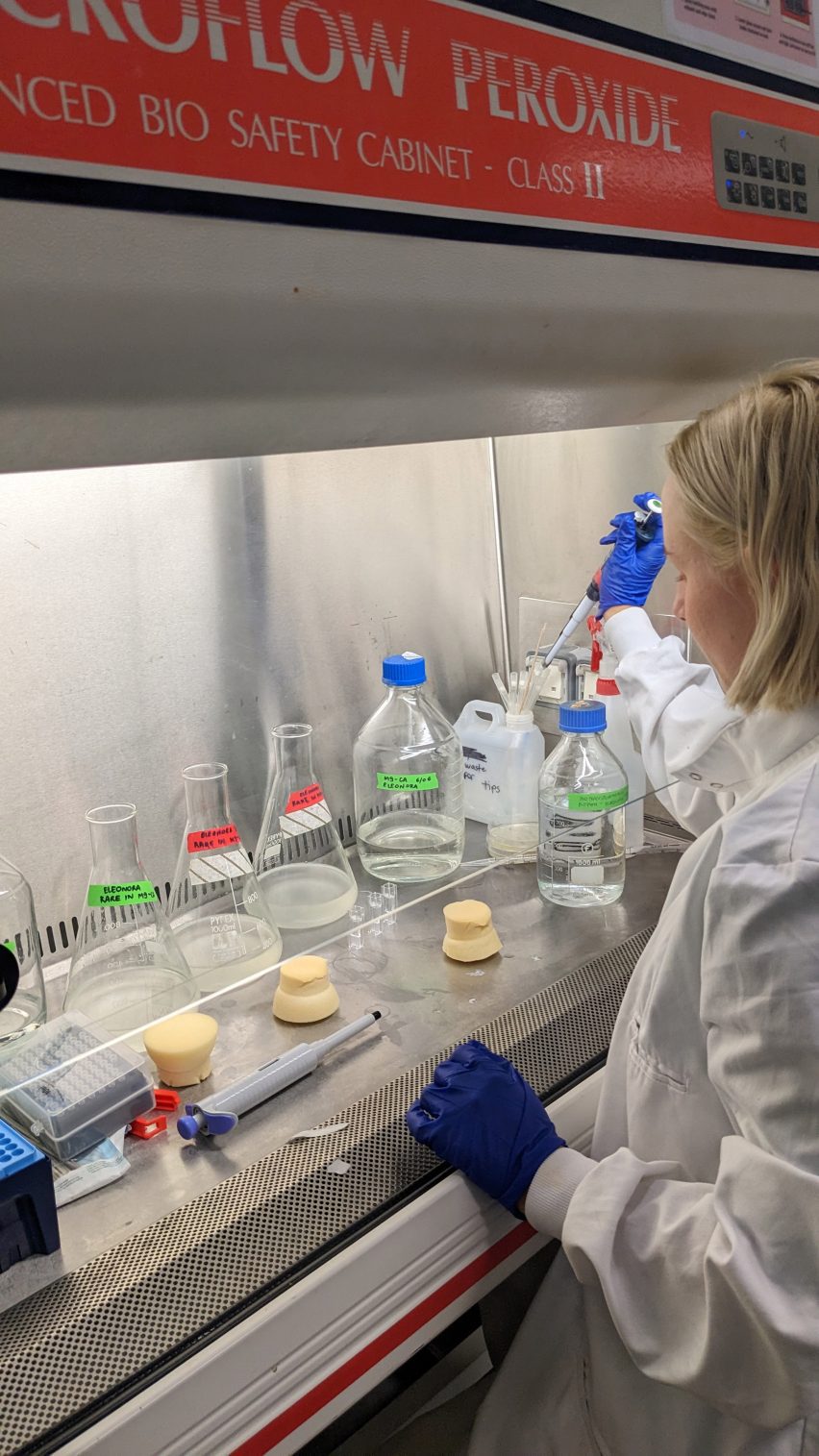

Ortolani replicated the scientists’ patented synthesising process in the CSM Grow Lab, using bacteria they had sent her in agar, instructions shared under terms of strict secrecy and 20 milligrams of PET.

She says the substance smells exactly like what we recognise as vanilla but she has never tasted it, and nor has anyone else.

Although the molecule may be chemically identical to existing synthetic vanillin, it is considered a completely new ingredient by food safety bodies, and the scientists will not allow tasting until it has undergone all the testing to be declared safe to ingest.

Instead of eating it, Ortolani presented the ice-cream in a locked fridge at the CSM graduate exhibition, and hopes her project will start a conversation about what we view as natural versus synthetic, and how those perceptions might be holding back our goals for food security in an era of climate change.

“If I tell you ‘there’s an ingredient in that ice-cream coming from plastic waste’, you’re going to be completely disgusted by it,” said Ortolani. “But then once you understand that basically everything is part of the same ecosystem and we can even consider plastic part of the same ecosystem, then it makes total sense.”

“We drastically have to change the way we eat and the way we perceive food. I’m not saying we have to look at the future of food as everything being synthetic or super-processed, but it’s just a matter of compromise for me,” she continued.

“What’s nature is constantly evolving, and for as long as we consider plastic as something external to nature, we’re not going to actually understand how to tackle the problem.”

Ortolani has recently been awarded a S+T+ARTS residency to continue her research, and hopes to involve chefs in the next stage of the work. She speculates that a similar process to what was used to turn the plastic into vanillin could one day be used to produce proteins or carbohydrates.

Parley for the Oceans founder Cyrill Gutsch has previously warned designers not to get complacent because of the discovery of plastic-eating enzymes and to continue to focus on the eradication of plastic.