Ronnie Scott is an RMIT academic and co-founder of the literary journal The Lifted Brow. His debut novel, The Adversary (2020), set mainly in the Melbourne suburb of Brunswick, was a wry exploration of the nuances of house sharing and online dating.

His second novel, Shirley, is also set in Melbourne’s inner-northern suburbs. Unlike the house in Abbotsford that gives the novel its title, the female narrator is nameless. As a child, she was abandoned by her food-celebrity mother after a controversial incident, left in the eponymous family house in the care of a series of business managers named “Gerald”. She has grown into a lonely adult, who still yearns to be seen by her mother.

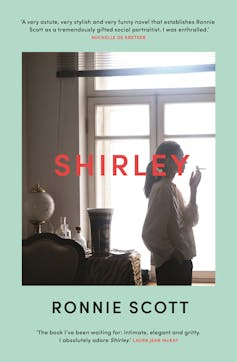

Review: Shirley – Ronnie Scott (Hamish Hamilton).

Having acquired a Masters of Global Communications, she now works as a copywriter for a health insurance company. She is past the years in her twenties when she would go out clubbing and fuck members of rock bands in share houses, and past her Gen-Z boyfriend, David. She attends Invasion Day rallies and expresses her concern for Gippsland’s bushfire victims. Childless, she enacts a wounded agency: “my smile stayed fixed”.

Psychological realism

Scott’s psychological realist novel spears the disorienting effects of 262 days of Melbourne lockdowns – although his protagonist is more financially secure than most of her cohort. She has a mortgage on a rundown apartment in Collingwood and a boring full-time job that allows her to work mainly from home. She half-heartedly becomes a boss. “I did a good job of living shallowly,” she states.

The novel’s narrative hooks entice:

the night at Shirley twenty years ago that had changed both our lives. What happened that night? It is a tempting question, and I will never answer it.

Frequent flashbacks then provide the circumstantial and psychological details, the protagonist sharing her confidences in the pensive tones of a diarist.

Shirley is not a book about racial or environmental politics. Nor is sexual fluidity in the foreground, though David is bi-curious and the last of the Geralds happily gay.

So what is at stake? What does Scott’s narrator need? Will a baby or a pet fix things? Or perhaps a mother’s love of a less meagre kind?

When “condiment maven” Frankie, barefoot and pregnant – surely an intended irony – moves next door with her employee and boy lover, there is a discussion about how a child is the answer to feelings of emptiness.

Yet our protagonist craves solitude. She wants to retreat, drink in hand, to her home space and smoke a cigarette. Her thought patterns seem cauterised by the trauma of abandonment. She robotically paraphrases her therapist as she ploughs through “empathy deserts” and soothes rather than engages with others: “It’s good that you know what you want.”

Noir and nostalgia inform Chris Womersley’s tale of forgery, grief, and the seamy side of urban life

Gender equity

The novel entertains on many levels. The prose in Shirley is assured, blackly funny and playful, though the register of some of the inner monologues may not appeal to all readers:

As it turns out, this is a febrile environment for extant tensions to aggravate; a time of peace doesn’t leave much time for prevarication.

Image: Leah Jing McIntosh/Penguin Books

Gender equity arises as a core subject, but the tone is tongue-in-cheek. The narrator’s female friends are millennial HENRYs (High Earning, Not Rich Yet), who – pre-COVID – liked décor and drugs, but not sex-tapes or music festivals like their boyfriends. They despair of finding equal partners and retaining their power over their younger lovers. The young men present as crumb bachelors, who need older women to give them a leg up. They are endearing in their gaucheness, if eventually tiresome.

The novel’s zeitgeisty narrative also satirises feminism, grief, mothering, relationships, and everything else, in a manner that is at times reminiscent of Nick Earls. Class, mainly aspirational, is touched upon. Celebrity food shows take a hit, the narrator’s distant mother serving as a synecdoche. And teachers of creative writing may greet Scott’s definition with glee: “a room full of people who had learned the word ‘petrichor’ at a vulnerable time and never got over it”.

Scott trusts his readers to follow the rapid reversals and dark satire. Consider, for example, this passage of dialogue between Frankie and her employee, Alex:

“We’re not really a couple,” said Frankie. Alex frowned. “Alex is a – well what would you call yourself?”

“I’m a gigolo,” Alex said.

“More like a sperm donor,” she corrected, “as well as a general dogsbody. With an option towards future parent duties.”

“We’re not in love,” said Alex.

“I make a lot of money,” agreed Frankie, “and I liked his genes.”

“You liked my chin and my behaviour,” said Alex. “You can’t see my genes.”

The protagonist’s loneliness can only be inferred from the long absence of her heartless mother and the alienation experienced by many singles during Covid lockdowns. She seems to be in an almost dissociated state. She seeks only clarification, or enough information in her relationships with others to calculate her personal boundaries. She mentions complex feelings before repressing memories that trigger them.

Novels can succeed in different ways. Shirley constantly invites its readers to switch gears from psychological identification to political and social satire. The psychological realism does not quite satisfy, but the satire enlivens. Each time it erupts, it lightens the tension.

Humane by inclination, or perhaps simply ambivalent, the narrator comes to care for Meanie, an ancient, abandoned, arthritic, diabetic cat. She is ultimately horny, sad, and stuck. In the novel’s final scenes, the word “need” appears six times.

Scott’s struggling, self-perceptive characters see themselves as vulnerable, yet smarter than their therapists. Could existential dread and irony come any funnier or more poignant? Whether readers find the ending redemptive might depend on how they weathered COVID, and how they feel about cats.