American business magnate Warren Buffett once famously observed: “You don’t find out who has been swimming naked until the tide goes out.”

Silicon Valley Bank was exposed last week by rising interest rates, leading to an old-fashioned bank run — where the bank’s customers rush to withdraw their money all at once.

The failure of the 16th-largest bank in the U.S. highlights the vulnerability of its niche business model in the digital age.

Could something similar happen in Canada? For the largest Canadian banks, the answer is no. But for smaller, niche financial service firms, recent history suggests they should not be complacent.

A vulnerable business model

The first step to assessing any vulnerability in Canada is understanding why Silicon Valley Bank failed.

Silicon Valley Bank ran a risky business. It used short-term cash deposits from technology clients to buy longer maturity U.S. mortgage bonds. This maturity mismatch may be profitable in good times, but can wipe out an investor in bad times.

The rise in interest rates over the past year resulted in US$2 billion of losses on Silicon Valley Bank’s bonds. Facing a potential credit downgrade, the bank tried but failed to raise equity to shore up its balance sheet.

When this news spread over social media, it led to rapid online withdrawals of deposits that drained Silicon Valley Bank’s cash reserves. U.S. regulators seized the bank to stop the bank run.

Short-term deposits fund long-term bonds

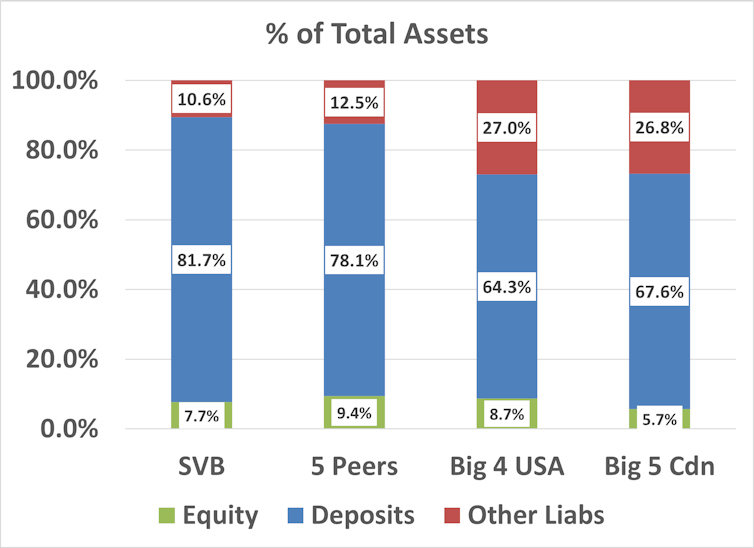

Silicon Valley Bank’s vulnerability can be seen by comparing its balance sheet to its peers. At the end of 2022, Silicon Valley Bank depended on short-term customer deposits to finance more than 80 per cent of its US$212 billion in assets.

(Michael R. King), Author provided

The five closest regional banks — Capital One Financial, First Republic Bank, KeyCorp, M&T Bank and U.S. Bancorp — had a similar share of assets. But the Big Four U.S. banks — JPMorgan Chase, Bank of America, Citigroup and Wells Fargo — had more diversified funding.

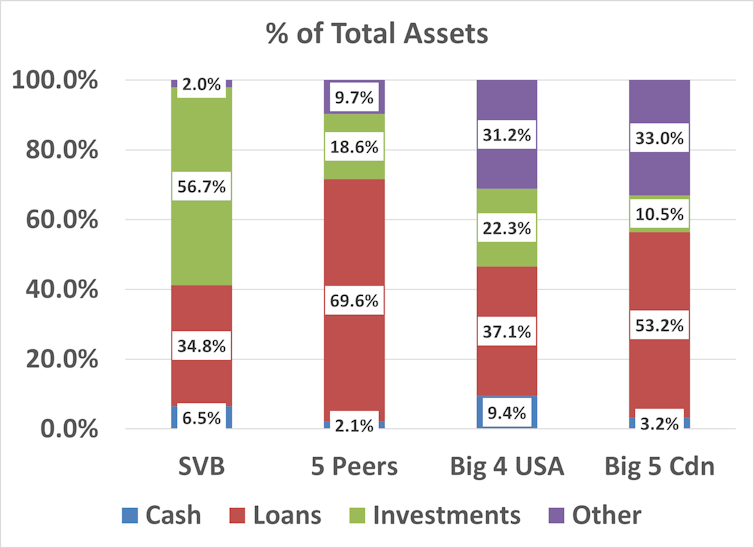

Silicon Valley Bank invested this cash in mortgage bonds and other securities, representing 60 per cent of its assets. Silicon Valley Bank’s figure was almost three times higher than its closest peers, and more than double the U.S. Big Four.

(Michael R. King), Author provided

To offset this risk, Silicon Valley Bank held more cash than its closest peers at six per cent of assets. But when the bank run started, the fire sale of bonds at a loss was not enough to offset the electronic withdrawal of deposits.

How safe are Canadian banks?

Could a similar bank run happen north of the border? The answer for Canada’s largest banks is no.

Canada’s Big Five banks — Royal Bank, TD Bank, Scotiabank, the Bank of Montreal and CIBC — remain among the safest in the world. They are large, diversified and well capitalized. They have experienced leadership and are closely monitored by a respected banking supervisor.

Canada’s Big Five have nearly identical funding profiles to the Big Four U.S. banks. The Big Five’s larger share of loans makes them arguably safer, as most Canadian mortgages are insured by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation.

Financial markets agree with this assessment. As of yesterday, the share prices of Canada’s Big Five were down 16 per cent on average over the past 52 weeks, similar to the 13 per cent drop for the Big Four U.S. banks.

By contrast, Silicon Valley Bank’s share price was down 80 per cent before trading halted last Friday. And Silicon Valley Bank’s five closest peers were down 40 per cent on average.

Innovation increases risk

This analysis does not imply there are no vulnerable players in Canada’s financial system. Silicon Valley Bank demonstrates that innovative, niche business models are more vulnerable.

(AP Photo/Peter Morgan)

This pattern fits the history of bank runs. The U.K. had not experienced a bank run in 140 years until the 2007 demise of Northern Rock. This niche lender relied on short-term funding from other banks to finance long-term mortgages. This mismatch brought down the lender when interbank markets froze at the start of the 2007-08 global financial crisis.

Canada had a partial bank run in 2017. Home Capital Group was a niche lender that offered uninsured mortgages to less creditworthy Canadians. This risky business was funded by high interest savings accounts and other deposits. When Home Capital’s depositors lost confidence, the partial bank run was only halted when a group of Canadian institutional investors threw Home Capital a $2 billion lifeline.

Three pillars underpin trust

These bank runs are a reminder that trust in banking is built on three pillars: risk management, deposit insurance and banking supervision.

All banks use leverage, making risk management a key success factor. Canada’s largest banks have demonstrated this ability over many decades, most recently during the global financial crisis.

Eligible deposits in Canada are insured by the Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation, a Crown corporation that insures up to $100,000 per account held at member institutions.

Federal financial institutions are supervised by the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions, which monitors capital levels and risk taking.

These three pillars are being tested as rising interest rates expose weaknesses in the global financial system. A decade of cheap money has fuelled many innovations and niche business models.

With an economic slowdown underway, more failures in the global financial system are bound to happen.