What is comedy?

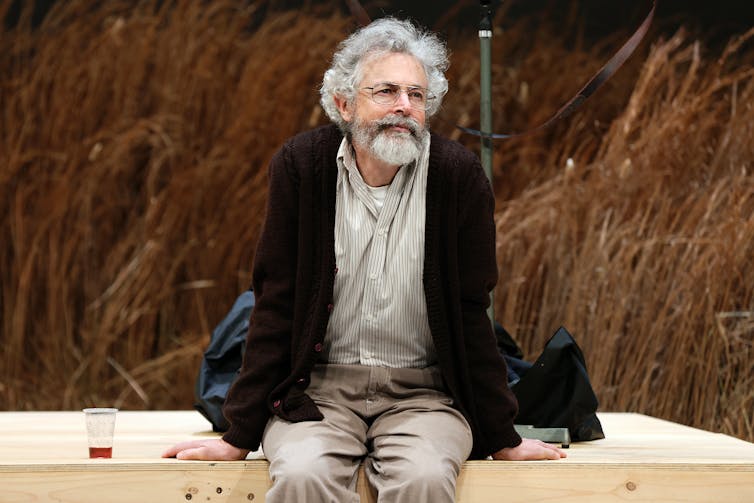

This is the question I kept coming back to while watching Andrew Upton’s adaptation of Anton Chekhov’s The Seagull, which opened to warm applause – and a touch of controversy – at the Sydney Theatre Company on Saturday.

Theatre scholar Eric Weitz notes that comedy is a genre “with characteristic features”.

Laughter, humour, distraction. These are some of the terms associated with comedy.

Comedy is also restless. As Weitz acknowledges, comedy “embraces a range of subgenres” and often “cross-pollinates with other genres to form the likes of tragicomedy”.

These cross-pollinations can often confuse.

Consider the very first performance of The Seagull, subtitled “a comedy in four acts”.

The notorious performance at the Alexandrinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg on October 17 1896 was an unmitigated failure. The audience jeered; the reviews were scathing.

Wikimedia Commons

In a letter sent to the publisher Aleksey Suvorin the very next day, a wounded Chekhov declared he would never again “write plays or have them acted”.

The reason why the premiere went so badly has to do with audience expectations. As essayist Janet Malcolm explains, there were special circumstances on the night in question.

The performance was part of a benefit event for E. I. Levkeeva, a popular Russian comic actress, “and so the audience was largely made up of Levkeeva fans, who expected hilarity and, to their disbelief and growing outrage, got Symbolism.”

Primed for broad comedy, the audience didn’t know what to do with Chehkov’s groundbreaking spin on the genre, which broke with established realist modes and placed emphasis on metaphorical imagery and allegorical tropes.

While the play, which speaks to the themes of art and desire, has many funny moments, it simultaneously foregrounds discussions of mortality and depictions of madness. And it ends with a suicide.

Moreover, Chekhov’s play is one where, as the academic James Loehlin writes

the old win out over the young, where hope and the impulse for change are crushed, in part through their own fragility and lack of conviction, but in part by the proficient ruthlessness of the seasoned old campaigners, their elders.

I mention this because the serious and subtle aspects of The Seagull – many of which continue to resonate today – can get lost in modern takes on Chekhov’s play.

This is true of the Sydney Theatre Company’s production. Adapted by Upton and directed by Imara Savage, this version showcases the sound work of Max Lyandvert and features a meta-theatrical set designed by David Fleischer.

Prudence Upton/Sydney Theatre Company

The adaptation is set in contemporary rural Australia and uses anglicised character names. Upton and Savage stick with Chekhov’s formal structure, but privilege the comedic at the expense of pretty much everything else when it comes to delivery.

This has ramifications for how the adaptation pans out.

The lies of happiness: living with affluenza but without fulfilment

Success beckons, tragedy befalls

The play comprises four acts and centres on four characters who mirror each other.

Constantine (Harry Greenwood) and Boris (Toby Schmitz) are writers. Boris is famous. Constantine – a college dropout who fancies his chances as an avant-gardist – is most definitely not.

Irina (Sigrid Thornton) and Nina (Mabel Li) are actors. Irina, who is Constantine’s mother and Boris’s lover, is a renowned stage star. The ingénue Nina, who is dating Constantine, desperately wants to make it.

Success beckons, but tragedy eventually befalls Nina – who leaves Constantine for Boris – in the two year gap between the play’s third and fourth acts.

These characters are joined by several others, including Irina’s ailing landowner brother Peter (Sean O’Shea), and a depressive young goth, Masha (Megan Wilding). With the exception of one, every character in the play is morose.

Prudence Upton/Sydney Theatre Company

The first act is structured around an abortive performance of an experimental theatre piece Constantine has worked up. Nina and Boris grow close in the second, while Irina holds court. At the start of the third act, it is revealed Constantine has tried to take his own life. Boris threatens to leave Irina for Nina. Hilarity ensues as Irina tries to win him back.

The atmosphere that the Sydney Theatre Company creative team establishes in each of these acts is lighthearted and largely humorous. Indeed, there are some moments, as when a gravely ill Peter convulses on the ground in the third act, when the onstage action almost tips over into outright farce.

As Chekhov himself insisted, different types of comedy – including farce – had roles to play in The Seagull. However, the overarching tonal emphasis in this adaptation causes problems in the play’s last act, which is set indoors during the Australian winter.

Peter, not long for the world, spends his time talking about how he regrets his entire life. The other characters fob him off. Constantine has made headway as a writer, but is deeply unhappy. He pines after Nina, who dropped off the radar somewhere between acts.

Prudence Upton/Sydney Theatre Company

Time passes, and trivialities exchanged. A bedraggled Nina reappears. The story she tells is one of sorrow and woe. A genuinely moving moment, the speech is delivered with real affective intensity – undoubtedly the high point of the production.

However, the tonal chasm between the final act and the preceding three is simply too great.

In keeping with Chehkov’s original, comedy ultimately gives way to tragedy, but something seems to have been lost along the way.

The Seagull is at the Sydney Theatre Company until December 16.

Belvoir’s The Master and Margarita: astonishingly ambitious, physically demanding and a resounding success

If this article has raised issues for you, or if you’re concerned about someone you know, call Lifeline on 13 11 14.