Contrary to the connotations of its title, Temperance is a novel of extremes. The narrative is built around two disappearances, which traumatically affect the lives of a woman and her children.

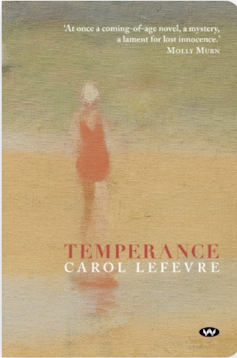

Review: Temperance – Carol Lefevre (Wakefield Press)

When she is heavily pregnant with her third child, Stella Madigan learns that her husband’s truck has plunged into the flood-swollen Darling River and he is missing, presumed drowned.

The novel opens some seven years later, in the Adelaide suburb of Brighton, where she is running the seaside café that had belonged to her parents, and raising her children alone – daughters Tess and Fran and son Theo, born after his father’s disappearance.

Enter Mardi Rose, a newcomer to this sleepy suburb, a dashing, Bohemian artist, who befriends Stella. Tess, at 16 and already rebelling against her mother, is scornful, but young Fran is won over by Mardi, who teaches her to draw, and makes much of her. Fascinated, Fran spies on the two women as they sit drinking on Mardi’s balcony; when they kiss, she is troubled, uncomprehending.

Their behaviour is altogether too much for the locals, and Mardi creates further scandal by teaching life drawing, sometimes herself acting as the model. Effectively run out of town by wowsers, Mardi persuades Stella to escape with her to “cruisy” Byron Bay, her old stamping ground. They set off on what promises to be a road trip to a new life.

At the end of the first day’s drive, Stella takes a wrong turn outside of Hay, and they are forced to camp overnight at the small town of Temperance. During the night, chaos – and tragedy – descend. Stella and her children take off, back the way they have come, back to Brighton.

The second part of the novel begins 14 years later. Fran is now a teacher, Theo a gardener, both still living at the café with their mother. Stella is shown crashing pots and burning her hands at the stove in the café, more angry and remote than ever. At school Fran takes under her wing a neglected child, Lauris, in whom she obviously sees her younger self.

Theo, still subject to the night terrors that haunted him as a child, tries to create harmony in gardens, especially through his fascination with making a labyrinth. More than a decade passes, and both siblings form relationships with others.

It is not until their mother’s death, years later, that the brother and sister can begin to take charge of their lives. The resolution of this novel takes the classic form of revisiting the buried past and revealing its secrets. Theo, who has been in analysis, insists on a return visit to Temperance, and there they are able – almost serendipitously – to find out what actually happened on that chaotic night. What they discover solves the mystery of both the significant disappearances from their childhood.

Elwira Lipko/Shutterstock

Tasmanian author Amanda Lohrey wins prestigious Miles Franklin Literary Award for The Labyrinth

Black holes

The novel’s three-part structure describes a classic arc of conflict, aftermath and resolution. Its time scale takes Fran and Theo from the ages of nine and seven, in the early 1960s, to adulthood 25 years later. Just as the central section forces readers to contain their desire to understand the mysterious events at Temperance, so too the final sequence is complicated – its discoveries delayed – by another major event happening simultaneously. A new life coincides with the promise of emotional recovery.

In a kind of epilogue, dated 1998, Fran is renovating the café, and discarding “old stuff”. She reflects:

She and Tess and Theo were who they were because of all that had happened to them, and while they would never be completely easy with it, they knew, too, that it could not be changed.

Temperance is about absence, disappearances, and the long-lasting effects of trauma. The trauma the children suffer is the result of the sudden and inexplicable events at Temperance, but they also have had to adapt themselves to living with an already traumatised and emotionally remote mother, and to the departure of their older sister, and mother substitute.

Temperance carries an epigraph, “The absent are always present” from Carol Shields’ The Stone Diaries, a novel which, incidentally, also features the death of a bridegroom. Shields’ story of a woman surviving multiple losses sets an admirable precedent for Lefevre’s novel, but here the emphasis is on the siblings and their relationships, rather than on a solitary survivor.

I was reminded of other powerful Australian novels about children coping with parental neglect – Romy Ash’s Floundering or Anna Spargo-Ryan’s The Gulf. The latter also shares a setting with Temperance, the gulf beaches of South Australia.

A novel about absence, Temperance is also a novel about place – the very present Adelaide beachside suburb of Brighton, sea and sand always glittering in the sun, and the distant town of Temperance in the middle of nowhere, the outer limit of their trajectory away from home, the turning point in their lives.

In this way, Lefevre evokes that pervasive settler image of Australia as a populous and beautiful coastline surrounding a vast, empty, mysterious centre, another kind of absence which is a constant presence. Fran imagines that

their father had rattled around in that great space until it claimed him […] Postcards portrayed the outback as endless red sand and blue sky, but Fran saw it as dark and pulsing, as dense and threatening as black holes.

Black holes in her memory shape the narrative. Always an anxious, hyper-vigilant child, there is much that she simply does not understand. As she grows up, her role as protector of others – first Theo, then her mother, and Lauris – seems to constrain her capacity to question and to articulate her observations.

Goodreads

For the most part readers can only share the limited points of view and perceptions of Fran and Theo.

Readers, then, are kept in the dark about some key events, not only what happened at Temperance, and the whereabouts of the disappeared, but also about the motivations of other characters. This deepens the sense of mystery. Stella is the silent presence at the centre of the story, and she takes her secrets to the grave.

Lefevre manages this difficult narrative point of view adroitly. She offers clues that point beyond the perceptions of these focal characters, in the form of motifs. One is that of the vanishing point: Fran learns from her art classes with Mardi about perspective, and later she remembers reading that “even shadows have vanishing points”. This offers her a clue to her father’s disappearance and, by implication, Mardi’s.

Another motif is the labyrinth. Theo learns from an old man, Hughie, how to create a labyrinth with plants, and this informs his later devotion to making gardens. Hughie tells the story of the Minotaur and Ariadne’s thread, and for Theo, learning that “labyrinths lead you to the centre, but a maze is a place where you can get lost” shows him a symbolic way of taking control of his life – to make a labyrinth rather than a maze.

Both motifs recall other significant novels, Thea Astley’s Vanishing Points (1992) and Amanda Lohrey’s The Labyrinth (2020), and suggest something of the place that this novel might occupy in the tradition of Australian women’s fiction.