On more than one occasion he declared that if he stopped working, he would die. And, indeed, death caught up with him at work.

On Friday 10 February 2023, Carlos Saura, one of the key figures of Spanish cinema, passed away. He had just released a documentary film (Las paredes hablan), signed the stage direction of a play about Spanish poet Federico García Lorca (Lorca por Saura) and was trying to set up a long-awaited film project about Picasso.

If one knows a bit about the career of this scriptwriter, novelist, filmmaker, photographer and painter, born in Huesca, Northern Spain, in 1932, it is not hard to understand the unstoppable creative torrent he gave way to.

Saura is easily the author of at least half a dozen milestones of Spanish cinema in the second half of the 20th century. La caza_ (1966), Peppermint frappé (1967), La prima Angélica (1973), Cría cuervos (1975) or Carmen (1983) are on film buff lists, in volumes of historiography or teaching manuals, as well as in the memory of many spectators.

At the same time, his enormous oeuvre as a photographer and painter, which has yet to be evaluated in its entirety, accredits him as one of the most brilliant and prolific image-creators born in Spain.

A cinema classic

All in all, Saura will be remembered first and foremost for his position as the w.

Most specialists agree in dividing his filmography into two periods. In the first, his films were associated with anti-Franco opposition and success, working with producer Elías Querejeta in the circuits devoted to auteur (or art-house) cinema.

FilmAffinity

His second period, which began after the Transition and saw him leave the “Querejeta factory”, allowed him to broaden his interests as a filmmaker, trying out new genres, narrative approaches and aesthetic paradigms. In general, this period, which includes peaks such as Deprisa, deprisa (1980), Bodas de sangre (1981), La noche oscura (1989), Flamenco (1995) or Iberia (2005), does not enjoy the critical appraisal of his first films.

This may be due, as scholars such as Manuel Palacio or Agustín Sánchez Vidal have pointed out, to the pedigree that his filmography acquired in the 1960s as an exponent of the anti-Franco discourse. When this faded with the establishment of the new democratic order, Spanish critics gradually turned their backs on a director who, paradoxically, experienced during the eighties his period of greatest international brilliance.

Spain’s international image

After Buñuel’s death and before Almodóvar’s breakthrough with Women on the verge of a nervous breakdown (1988), Carlos Saura was Spain’s cinematic ambassador in international arenas.

For a time, Spain, cinematographically speaking, was equivalent to the imaginary that Saura lavished in his allegorical and mysterious cinema of the late Francoism, the naturalistic images of Deprisa, deprisa or the stripped down and self-conscious musical films with dancer Antonio Gades. These were works that brought him a singular international success when in Spain critics and audiences, with the exception of ¡Ay, Carmela! (1990), turned their backs on his films.

FilmAffinity

To this day, Saura is the Spanish filmmaker who has won the most awards at class A festivals (Cannes, Berlin and Venice) and has received the most recognition from foreign institutions.

This probably led to him being the filmmaker chosen to shoot prestigious commissions such as Sevillanas (1992), for the Universal Exhibition in Seville in 1992, or Marathon (1992), the official film of the Barcelona Olympic Games, also in 1992. His fame as an official Spanish translator even enabled him to shoot an exotic spot for the French soft drink Orangina.

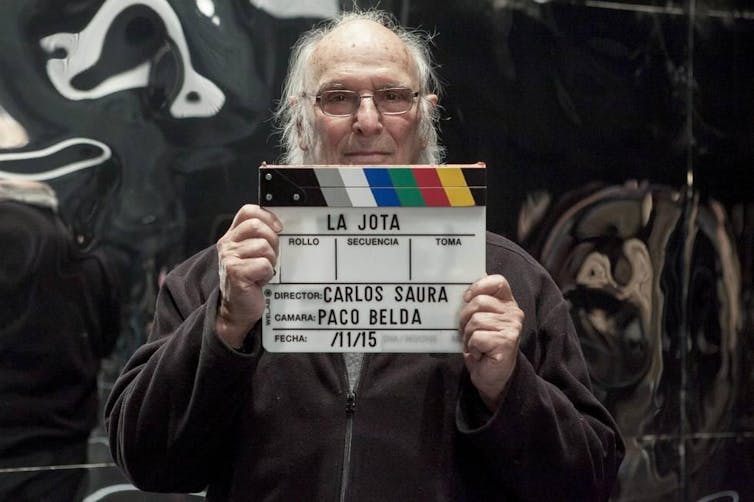

This same fame undoubtedly led him to delve into the vein of musicals “with an accent” that he made until the end of his career, which included explorations of flamenco, jota, sevillana, Mexican corrido, tango and northern folklore from Argentina, and Portuguese fado.

These films helped him to develop an unusual and increasingly refined inter-artistic dialogue, to revisit and reformulate a series of Ibero-American imaginaries associated with the popular or folkloric and, finally, to redefine his own image as a filmmaker associated with “the Spanish”.

The Salamanca generation

With Saura, the last vestige of one of the most important generations in the evolution of Spanish cinema disappears. He was a student and later a teacher at the Instituto de Investigaciones y Experiencias Cinematográficas (IIEC, later known as the Escuela Oficial de Cinematografía). He also took part in the Salamanca talks, a conference organised in 1955 between different personalities from the Spanish film world to discuss the future of Spanish cinema after the civil war. Saura belonged to a generation that fought to change the face of an industry subjected to the dictates of the Franco regime.

Considered a member, along with Mario Camus, Julio Diamante, Basilio Martín Patino and Miguel Picazo, of the so-called New Spanish Cinema, Saura made a place for himself among the most outstanding filmmakers of the European new waves. Although he paid the price of censorship in Spain, not to mention the cynical use of his films as a form of external legitimisation for the dictatorship, he became a point of reference for cinephilia worldwide.

FilmAffinity

Saura, in addition to all that, also forms part of a pantheon of European filmmakers who have worked tenaciously and rethought their work until their last day. In a recent colloquium on his work held at the Cervantes Institute in Paris, he refused to be called a “classic”, which for him meant becoming petrified, apoltronised, in short: stopping.

In this sense, Saura has always managed, in his perpetual renewal, to remain faithful to an idea of modernity which is what animated other great names such as Agnès Varda, Karel Vachek, Marco Bellocchio or Costa-Gavras, and which have built the history of the best European cinema.