James Cameron’s Avatar 2: The Way of Water, is released worldwide today. It’s the long-awaited sequel to Avatar (2009), also directed by Cameron, and has cost an enormous amount of money to make.

Some sources list the budget at around $350 million dollars, meaning it will need to make upwards of $2 billion at the worldwide box office just to break even.

But do we actually need this sequel? Do people remember the original Avatar? Aside from the 3D glasses and 10-foot tall aliens, what was memorable about it? Is Avatar in fact not a blockbuster, but a forgotbuster?

When it comes to describing a certain type of film, the word blockbuster dates back nearly 80 years. It was first used in the 1940s in film trade magazines such as Variety and Motion Picture Herald. It was in the 1970s – with the release of Jaws (1975) and Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) – that the concept of the blockbuster became commonplace.

Ever since, the term has been used to described a certain type of (usually) Hollywood film – full of CGI and special effects, with a fast-paced and action-packed narrative, full of memorable heroes, villains and one-liners, and financially lucrative at the box office.

Blockbusters are not just highly mediatised, extraordinarily successful films on their own merits, but they also become part of the cultural conversation for years to come. Modern-day equivalents include the likes of Avengers: Endgame (2019), The Matrix (1999), Top Gun: Maverick (2022), and The Dark Knight (2008).

Avatar: The Way of the Water review – tired climate clichés distract from Cameron’s vision

What is a forgotbuster?

The term “forgotbuster” was first coined by US film critic Nathan Rabin in 2013 to describe those movies that were among the top 25 grossing films the year of their release, but have receded culturally.

In other words, forgotbusters attracted huge numbers of audiences at the time, but have failed to endure. Rabin’s first example was Monster-In Law (2005), a now largely forgotten comedy vehicle for Jane Fonda and Jennifer Lopez. Rabin’s subjective list would also include the likes of Hannibal (2001), Disclosure (1994) and What Women Want (2000). By far his most controversial choice was Avatar.

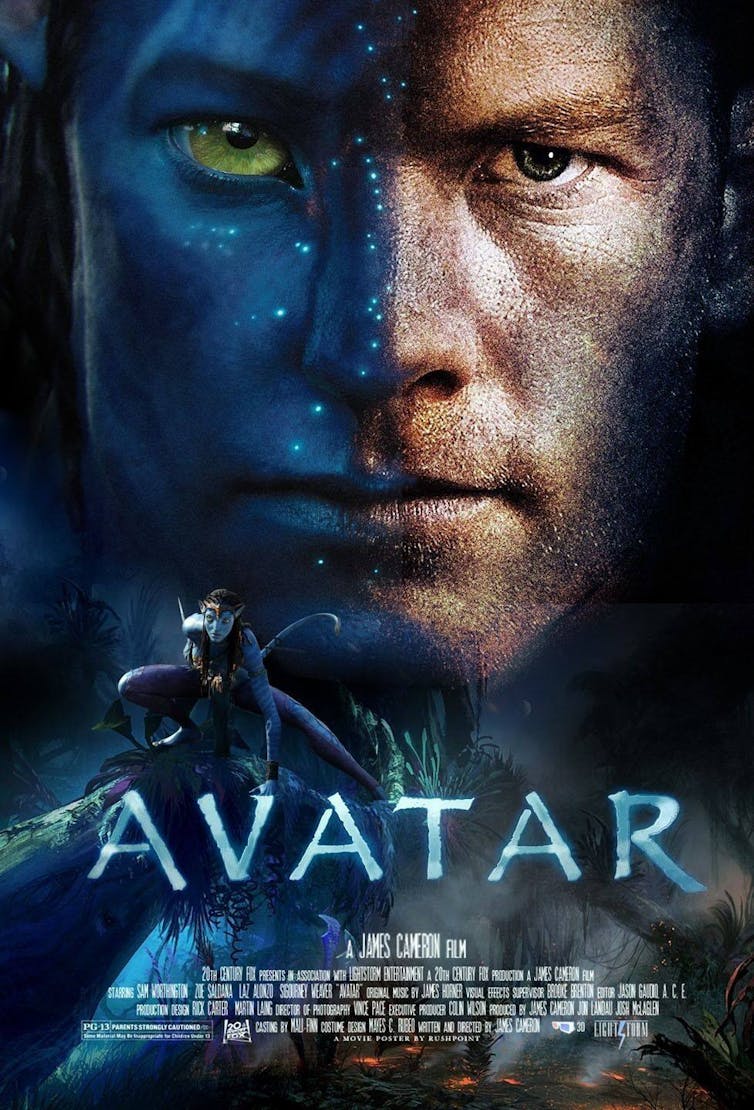

On its release in December 2009, Avatar quickly became a staggering financial success. Unadjusted for inflation, it remains to this day the most successful film ever made in terms of box office receipts. It was nominated for nine Academy Awards (winning three) and briefly brought 3D technology to the mainstream. It was lauded for its exquisite world-building and the IMAX grandiosity of its special effects.

20th Century Studios

Some fans even admitted to experiencing depression after seeing the film as they realised the alien world Pandora where most of the film takes place was not real. Several billion dollars later, James Cameron announced he was not going to make just one sequel, but potentially four.

The critic Roger Ebert described the film as “an Event, one of those films you feel you must see to keep up with the conversation”. But do people still talk fondly or nostalgically about Avatar in the way they do, say, Lord of the Rings (2001-2003), Star Wars, or James Cameron’s other era-defining films like Terminator 2: Judgement Day (1991) and Titanic (1997)?

Why hasn’t Avatar seeped into our cultural consciousnesses the way other films have? Rubin’s answer was unequivocal – he criticised the film’s “weaknesses and instant datedness”, focusing particularly on the poor acting.

What makes Avatar a forgotbuster?

I think there are three other reasons Avatar might be regarded as a forgotbuster.

Firstly, Avatar encouraged film studios to subsequently hike ticket prices based on a “3D premium”. Paying $15 for a regular ticket suddenly became $20 for Avatar and the dozens of movies that followed in the period from late 2009 to mid-2012.

Films were often retrofitted for 3D as studios sought to capitalise on Avatar’s success. This resulted in many sub-standard films being released that offered this supposed 3D experience – and cast Avatar as the film responsible for this surge in bad 3D.

Secondly, beyond its technological advances and impressive visual feats, what else do we remember from Avatar? What was the name of the lead character? Or the planet he landed on? Or the tribe he spent time with?

Avatar’s frozen-in-time memorability stems in large part from its status as an “event”. People went to the cinema multiple times, with family, then friends, then again alone, each time slipping on the 3D glasses and watching in awe at the immersive visual spectacle.

Unlike Cameron’s other classic films, full of indelible figures like Ripley in Aliens (1986) or Arnold Schwarzenegger in The Terminator (1984), Avatar lacks memorable characters or iconic lines.

20th Century studios

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, Avatar is not like other contemporary blockbusters. It is not a sequel, or part of a connected cinematic universe (yet), or based on an existing property. It is not full of star names. It trades heavily on ecological, pro-environmental, and anti-military themes.

Because Avatar isn’t a brand like Harry Potter, Star Wars or DC Comics, it lacks the cultural stickiness those franchises rely on to stay relevant in our saturated media landscape. Avatar burned brightly, and then was forgotten.

Avatar’s cultural footprint was temporary. What will happen to Avatar 2? Will it endure?

Despite the mixed reviews, the early indications are Cameron’s sequel will be a roaring commercial success, and will presumably gross in excess of $2 billion at the global box office. Avatar 3 is due in December 2024, and two more sequels have been greenlit.

Perhaps this extended Avatar universe will ultimately help both the sequels and the original re-enter popular culture and remind us of Cameron’s impressive skill at blending action, special effects, and the narrative beats that define the contemporary blockbuster.