In Thailand, Cambodia and Sri Lanka, Buddhists see strong links between their religion and country, as do Muslims in Malaysia and Indonesia

For this report, we surveyed 13,122 adults across six countries in Asia, using nationally representative methods. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. They were conducted on mobile phones in Malaysia and Singapore. Local interviewers administered the survey from June to September 2022, in eight languages.

This survey is part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, a broader effort by Pew Research Center to study religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America; Israel; Central and Eastern Europe; Western Europe; India; and the United States.

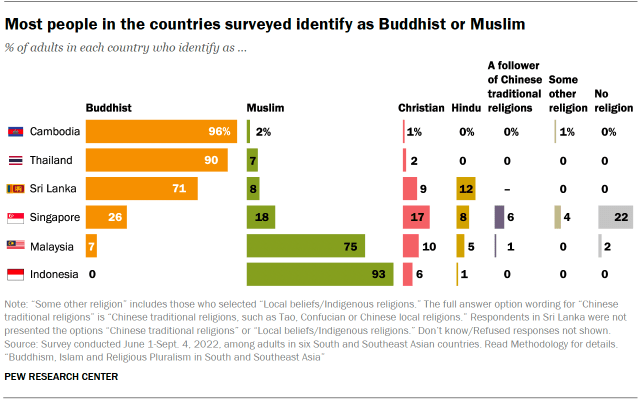

This survey includes three countries in which Buddhists make up a majority of the population (Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand); two countries with Muslim majorities (Malaysia and Indonesia); and one country that is religiously diverse, with no single group forming a majority (Singapore). We also are surveying five additional countries and territories in Asia, to be covered in a future report.

To improve respondent comprehension of survey questions and to ensure all questions were culturally appropriate, Pew Research Center followed a multiphase questionnaire development process that included consultations with academic experts, as well as focus groups and in-depth interviews across several Asian countries. In addition, a pretest was conducted in each country before the national survey was fielded. The questionnaire was developed in English and translated into seven languages. Professional linguists with native proficiency independently checked the translations.

Respondents were selected using a probability-based sample design. In Thailand, this included additional interviews in the country’s Southern region, which has larger shares who are Muslim. Data was weighted to account for different probabilities of selection among respondents and to align with demographic benchmarks for each country’s adult population.

For more information, refer to the report’s Methodology section or the full survey questionnaire.

How we chose the countries in this study

Previous Pew Research Center surveys on religion around the world have focused on well-defined geographic regions, individual countries or particular religious groups. The collection of six countries in this survey – three with Buddhist majorities, two with Muslim majorities and one that is religiously mixed – may seem like a less natural grouping. While the countries are fairly close to each other geographically, not all six are in Southeast Asia (Sri Lanka is typically grouped with South Asia), and several other Southeast Asian countries are not included in the study.

However, a key goal of the survey is to explore religion in Southeast Asia, and Buddhism in particular. This survey includes three of the world’s seven Buddhist-majority nations – Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand. Buddhists in these countries predominantly follow the Theravada tradition, a key reason for including Sri Lanka, which also has longstanding cultural and religious ties to some Southeast Asian countries.

Laos and Myanmar (also called Burma) also are Southeast Asian, Buddhist-majority countries in the Theravada tradition, but political realities and security concerns in those countries did not allow for reliable, independent surveys to be conducted on sensitive topics at this time.

This survey also includes the Muslim-majority countries of Indonesia and Malaysia as well as the religiously diverse country of Singapore to offer comparative perspectives on the intersection of religion and national identity in Southeast Asia.

As some practices and philosophies related to Buddhism have become more commonplace in the United States and other Western countries, many Americans may associate Buddhism with mindfulness or meditation. In other parts of the world, however, Buddhism is not just a philosophy about mind and body – it is a central part of national identity.

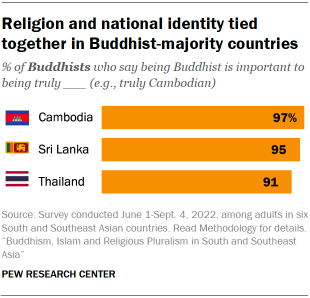

In Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand – countries where at least 70% of adults are Buddhist – upward of nine-in-ten Buddhists say being Buddhist is important to being truly part of their nation, according to a 2022 Pew Research Center survey of six countries in South and Southeast Asia.

For instance, 95% of Sri Lankan Buddhists say being Buddhist is important to be truly Sri Lankan – including 87% who say Buddhism is very important to be a true Sri Lankan.

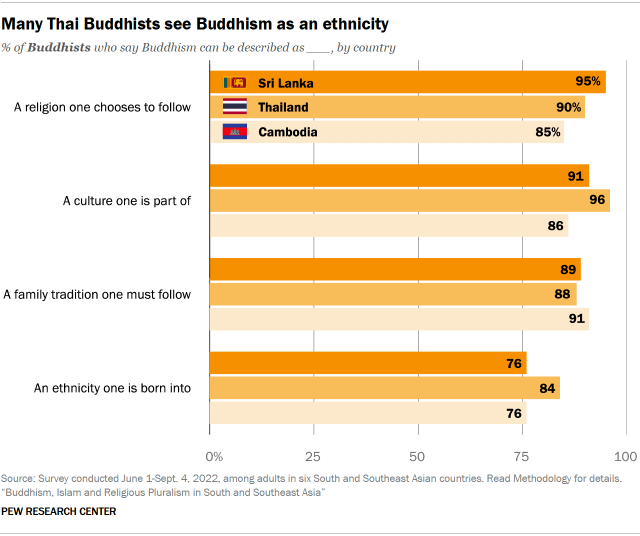

Although most people in these countries identify as Buddhist religiously, there is widespread agreement that Buddhism is more than a religion. The vast majority of Buddhists in Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand not only describe Buddhism as “a religion one chooses to follow” but also say Buddhism is “a culture one is part of” and “a family tradition one must follow.”

Most Buddhists in these countries additionally see Buddhism as “an ethnicity one is born into” – 76% of Cambodian Buddhists hold this view, for example.

Buddhism and national law in Buddhist-majority countries

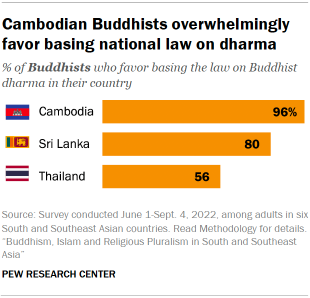

The importance of Buddhism in national identity is reflected in the prominence that all three countries’ laws give to Buddhism. Under Cambodia’s constitution, Buddhism is the national religion and the state is required to support Buddhist schools. Sri Lanka’s current constitution guarantees Buddhism “the foremost place” and assigns the government responsibility “to protect and foster” it. And a succession of Thai constitutions over the last century have increased the official preeminence of Buddhism, with the country’s most recent constitution requiring the state to “have measures and mechanisms to prevent Buddhism from being undermined in any form.”

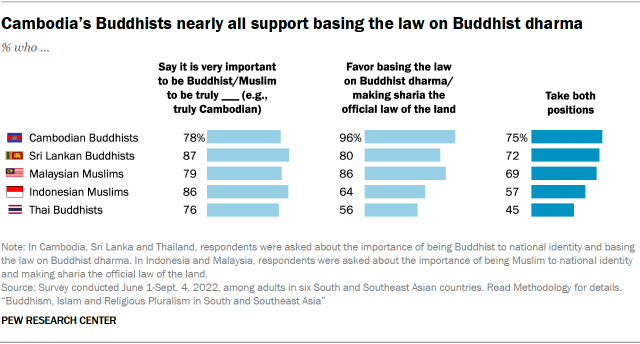

According to the survey, most Buddhists in all three countries favor basing their national laws on Buddhist dharma – a wide-ranging concept that includes the knowledge, doctrines and practices stemming from Buddha’s teachings. This perspective is nearly unanimous among Cambodian Buddhists (96%), while smaller majorities of Buddhists in Sri Lanka (80%) and Thailand (56%) support basing national laws on Buddhist teachings and practices.

Religious leaders’ role in politics

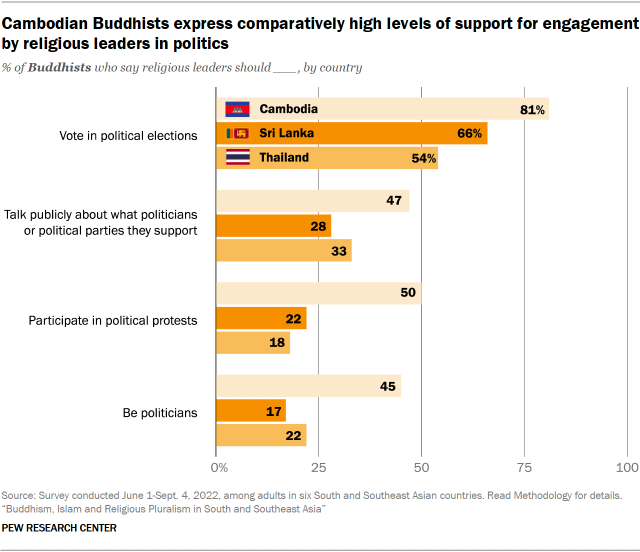

When asked about the role of religious leaders in public life, Cambodian Buddhists again stand out as the most likely to favor an intersection between religion and government. For instance, 81% of Cambodian Buddhists say religious leaders should vote in political elections, a position taken by smaller proportions of Buddhists in Sri Lanka (66%) and Thailand (54%). (The Thai constitution bans Buddhist monks, novices, ascetics and priests from voting.)

But even in Cambodia, with its near-unanimous support for basing the law on Buddhist dharma, no more than half of Buddhists say religious leaders should participate in political protests (50%), talk publicly about the politicians they support (47%) or be politicians themselves (45%).

Islam’s role in Indonesia and Malaysia

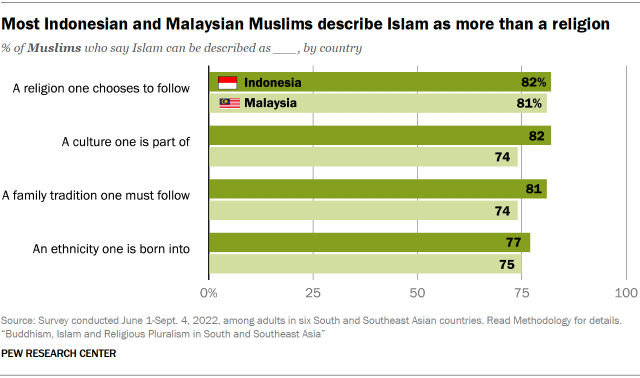

In some ways, Buddhism’s links to national identity in these countries parallel the role of Islam in the neighboring Muslim-majority countries of Indonesia and Malaysia. Nearly all Muslims in both countries say being Muslim is important to be truly Indonesian or Malaysian. And Muslims in both countries commonly describe Islam as a culture, family tradition or ethnicity – not just “a religion one chooses to follow.” For instance, three-quarters of Malaysian Muslims say Islam is “an ethnicity one is born into.”

Since emerging from colonial rule in the 20th century, these two countries have followed divergent paths for the role of religion in government, but most Muslims in both nations favor making sharia the official law of the land. Muslims in Malaysia, where Islam is the official religion, overwhelmingly support using sharia as the national law (86%). Most Malaysian Muslims also favored making Islamic law the official law of the land a decade earlier, in a 2011-2012 Pew Research Center survey of countries with large Muslim populations.

Support for sharia is somewhat lower among Muslims in Indonesia, where the drafters of the 1945 constitution ultimately rejected proposed language that would have explicitly favored Islam but included language saying the state is “based upon the belief in the One and Only God.” The resulting compromise is sometimes classified as “mild secularism” with “relative (not absolute) separation between state and religion.” Today, 64% of Indonesian Muslims nevertheless say sharia should be used as the law of the land. A majority of Muslims in the country likewise supported making Islamic law the official national law when asked in 2011-2012.

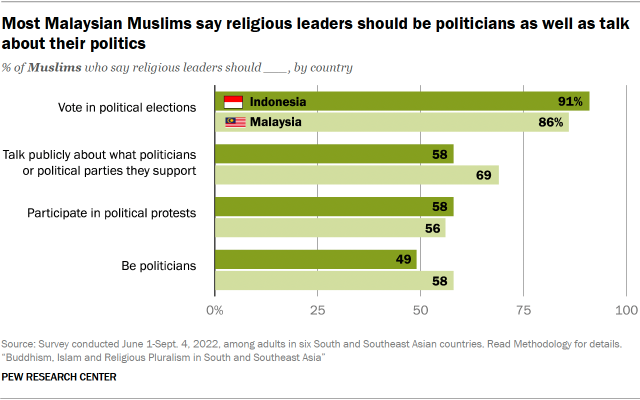

Muslims in both Indonesia and Malaysia are more likely than Buddhists surveyed in neighboring countries to favor high-profile roles for religious leaders in politics. For example, most Muslims in Indonesia (58%) and Malaysia (69%) say religious leaders should talk publicly about the politicians and political parties they support, while roughly half or fewer of Buddhists in Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand favor this level of religious interaction in politics.

Attitudes toward other religions

Alongside these three Buddhist-majority and two Muslim-majority countries, the survey also included Singapore, which has no religious majority and by some measures is the world’s most religiously diverse society. According to the most recent census, 31% of Singaporean adults identify as Buddhist, 20% are religiously unaffiliated (i.e., they say they have no religion), 19% are Christian and 15% are Muslim. The remaining 15% of the population includes Hindus, Sikhs, Taoists and people who follow Chinese traditional religions, among others. (For more on Singapore’s religious composition and how it has changed over time, read “Singapore’s changing religious identity.”)

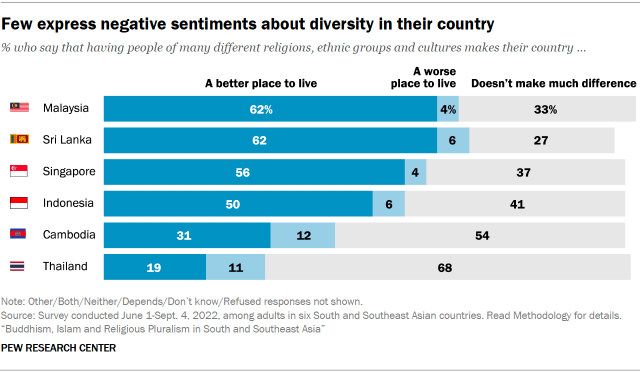

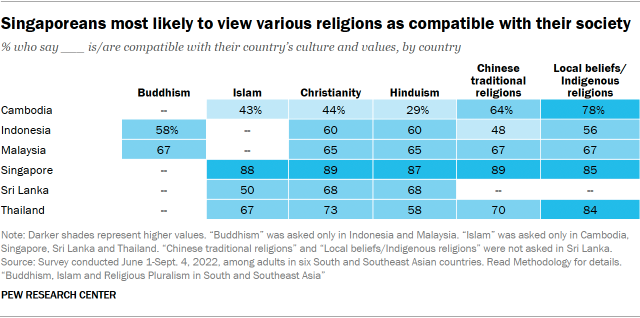

Most Singaporeans (56%) say that having people of many different religions, ethnic groups and cultures makes their country a better place to live, while few Singaporeans (4%) say it makes their country a worse place to live. (Most other respondents, 37%, say such diversity doesn’t make much difference.) And on several measures of religious tolerance, Singaporeans express broadly accepting views toward other groups. For example, nearly nine-in-ten adults in Singapore say Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Chinese traditional religions are all compatible with Singapore’s culture and values.

While Singapore sometimes stands out for the high levels of tolerance its residents express, adults in Malaysia and Sri Lanka (both 62%) are even more likely than those in Singapore (56%) to say that religious, ethnic and cultural diversity benefits their country. In general, tolerance for other religions is widely espoused in all six countries. Across all major religious groups, most people say they would be willing to accept members of different religious communities as neighbors. For instance, 81% of Sri Lankan Buddhists say they would be willing to have Hindu neighbors, and a similar share of Sri Lankan Hindus (85%) say the same about Buddhists.

And, overall, people in most of the countries surveyed tend to see other religions as compatible with their national culture and values. In Muslim-majority Malaysia, 67% say Buddhism is compatible with Malaysian culture and values. And even in Sri Lanka, where a civil war concluded a little more than a decade before the survey, 68% of the population says Christianity and Hinduism are compatible with Sri Lankan culture and values – including 60% of the country’s Buddhists (the majority community).

What are Chinese traditional religions and Indigenous religions?

The category of “Chinese traditional religions” is a fluid yet essential one. In several Southeast Asian countries, many people with Chinese ethnic backgrounds practice traditional ritual activities in temples that are devoted to Confucian, Mahayana Buddhist and Taoist deities, without necessarily seeing clear boundaries between them.

In other words, although Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist religious traditions are distinct from one another, the lines between them are fluid in practice. Furthermore, people who follow these practices may not claim a distinct religious identity.

Local beliefs and Indigenous religions refer to religions that are closely associated with a particular group of people, ethnicity or tribe. Such religious traditions may be less institutionalized than other religions that have a global presence, and the boundaries between Indigenous religions and other religions can be blurry.

Not only do religious groups largely accept one another as neighbors and fellow citizens, but in many cases, there also are signs of shared religious beliefs and practices across religious lines. For example, sizable majorities in nearly every large religious community in all six countries say that karma exists, even though belief in karma (the idea that people will reap the benefits of their good deeds, and pay the price for their bad deeds, often in future lives) is not traditionally associated with all the religious groups surveyed.

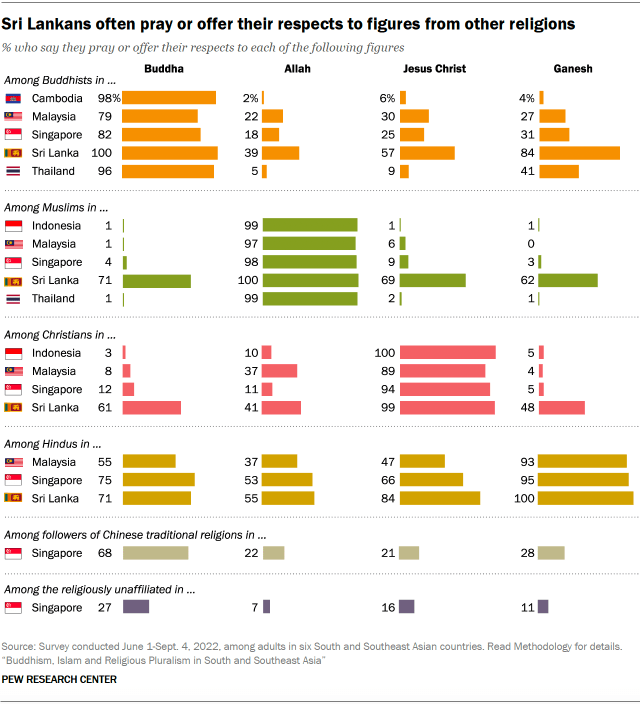

In addition, many people pray or offer their respects to deities or founder figures that are not traditionally considered part of their religion’s pantheon. For example, 66% of Singaporean Hindus say they pray or offer respects to Jesus Christ, and 62% of Sri Lankan Muslims do the same to the Hindu deity Ganesh.

“Offering respects” to deities – often through gestures such as bowing one’s head or putting one’s hands together – is commonly understood in the region as the act of worshipping or venerating deities and can include a variety of practices, such as burning incense, making food offerings or making wishes to the deity. These are gestures of great respect or veneration, though they may not align with formal, Western perceptions of prayer or worship. (For more on the figures people pray or offer their respects to, read “Praying or offering respects to figures from other religions.”)

Clear divisions – and tensions – between religious groups

Despite these expressions of tolerance and religious mixing, religious identity also can be a firm line between groups in this part of the world.

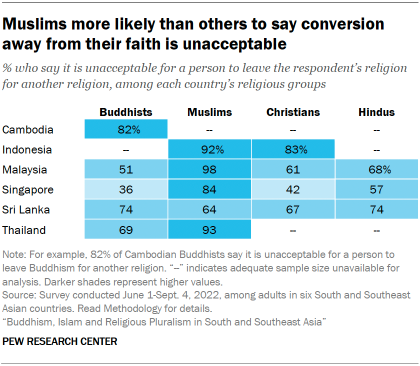

In fact, many people across the countries surveyed say it is unacceptable for people to give up their religion or convert to another faith. In Indonesia, 92% of Muslims say it is unacceptable for a person to leave Islam, and 83% of Christians say it is unacceptable to leave Christianity for another religion.

Overall, Muslims are more likely than other religious communities to say conversion away from their faith is unacceptable. But this is also the position taken by two-thirds or more of Buddhists in Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand – the study’s three Buddhist-majority nations.

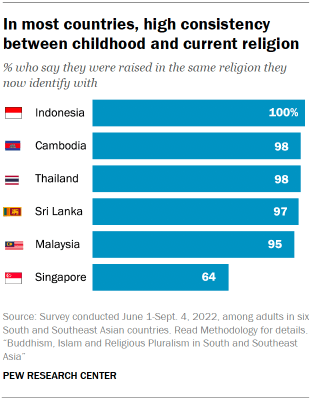

In five of the six countries surveyed, nearly all adults still identify with the religion in which they were raised. Only in Singapore do a sizable share of adults (35%) indicate their religion has changed during their lifetime. (For additional information on religious switching in Singapore, read “Share of Singaporeans identifying as Christian or unaffiliated is increasing.”)

Moreover, in several countries, substantial shares see other religions as incompatible with their national culture and values. For instance, 45% of Sri Lankan Buddhists say Islam is incompatible with Sri Lankan values, while 38% of Indonesian Muslims say Buddhism is incompatible with Indonesian culture.

In some countries, there are also sizable shares of Muslims who say Buddhism is not peaceful, and conversely some Buddhists who say Islam is not peaceful. Malaysian Muslims are especially likely to see Buddhism as not peaceful (42%), while 36% of Thai Buddhists say Islam is not peaceful.

In some countries, substantial shares express negative feelings about Christianity and Hinduism. In Indonesia, for example, 21% of Muslim adults surveyed say Christianity is not peaceful.

These are among the key findings of a Pew Research Center survey conducted among 13,122 adults in six countries in Southeast and South Asia. Interviews were conducted face-to-face in Cambodia, Indonesia, Sri Lanka and Thailand and on mobile phones in Malaysia and Singapore. Local interviewers administered the survey from June to September 2022, in eight languages. (Read the report’s Methodology for further details.)

This study, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of a larger effort by Pew Research Center to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America; Israel; Central and Eastern Europe; Western Europe; India; and the United States.

The rest of this Overview covers various topics in more detail, including:

Unique patterns of belief across a highly religious region

In general, the countries surveyed are highly religious by a variety of measures – including affiliation, beliefs and practices. For instance, nearly all respondents in five of the six surveyed countries identify with a religious group, and majorities in these same five countries say religion is very important in their lives – including 98% in Indonesia and 92% in Sri Lanka.

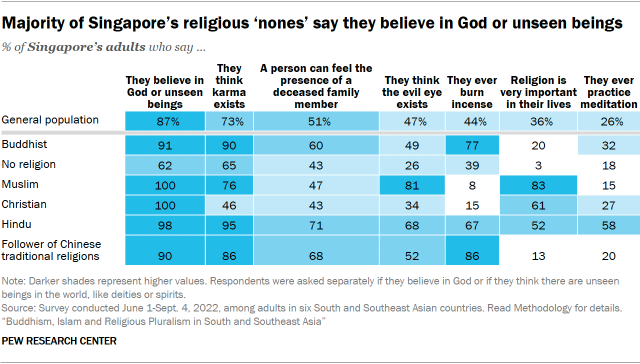

The lone exception on both these measures is Singapore, where 22% of adults do not identify with any religion, and just 36% of adults say religion is very important in their lives.

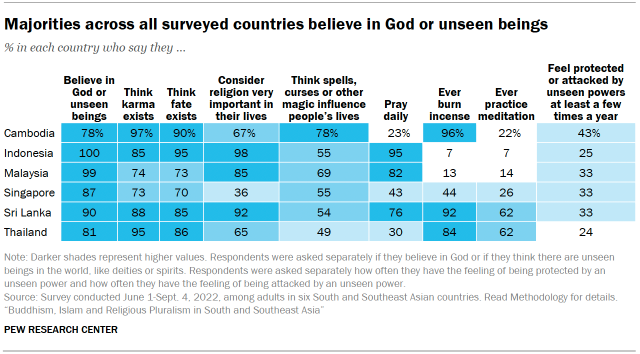

Even in Singapore, however, the vast majority of adults surveyed (87%) say they believe in God or unseen beings, and about seven-in-ten say they think karma and fate exist. These beliefs are common across all the countries in the survey, as is the notion that spells, curses or other magic can influence people’s lives. Roughly half or more adults in each country hold this view, including 55% in Singapore and 78% in Cambodia.

Rates of specific religious practices often are related to the religious makeup of each country. For example, overwhelming majorities in Cambodia (96%), Sri Lanka (92%) and Thailand (84%) say they burn incense; all three are Buddhist-majority countries, and Buddhists across southern Asia are more likely than Hindus, Christians or Muslims to burn incense. Meditation is also highest in the Buddhist-majority countries of Thailand and Sri Lanka (62% each), although Hindus across the region are more likely than Buddhists to say they practice meditation.

By contrast, daily prayer is most common in Indonesia and Malaysia, the two Muslim-majority countries in the survey. And, across the region, Muslims are more likely to say they pray at least once a day than are Hindus, Christians or Buddhists.

By multiple measures, religiously unaffiliated adults in Singapore are among the least religious or spiritual people in the region. But sizable shares of unaffiliated Singaporeans do express some religious or spiritual beliefs or follow some practices. (For a more detailed look at Singapore’s unaffiliated population, read “Who are the people in Singapore who don’t identify with a religion, and what do they believe?”)

Praying or offering respects to figures from other religions

In the countries surveyed, many religious beliefs and practices are shared by different religious communities. This includes a propensity to show respect for – or even to pray to – deities or religious figures commonly associated with another faith.

For instance, nearly one-in-five Singaporean Buddhists (18%) say they pray or offer their respects to Allah, while almost half of Malaysian Hindus (47%) say they pray or offer respects to Jesus Christ.

In general, Hindus are the most likely to pray or offer their respects to deities or founder figures not traditionally associated with their community, while Muslims are generally the least likely to do this. For example, in Singapore, 66% of Hindus and just 9% of Muslims say they pray or offer respects to Jesus Christ. In fact, Singapore’s religiously unaffiliated adults (16%) are more likely than the country’s Muslims to say they pray or offer respects to Jesus Christ.

Sri Lanka, an island nation south of India, also stands out as a place where people pray or offer respects to founder figures and deities – both the ones traditionally associated with their religion and those from other traditions. For instance, 48% of Sri Lankan Christians say they pray or offer their respects to Ganesh, the Hindu god of beginnings who is considered a remover of obstacles. But in the other countries surveyed, only about 5% of Christians do so. And 71% of the island’s Muslims say they pray or offer respects to Buddha, while very few Muslims in the other countries surveyed do this.

In addition to Buddha, Allah, Jesus Christ and Ganesh, the survey also asked about Mother Mary, Shiva, Guanyin and “protector spirits” in general. For more about people’s relationships with deities, spirits and religious founder figures, read Chapter 4.

Religious funeral practices

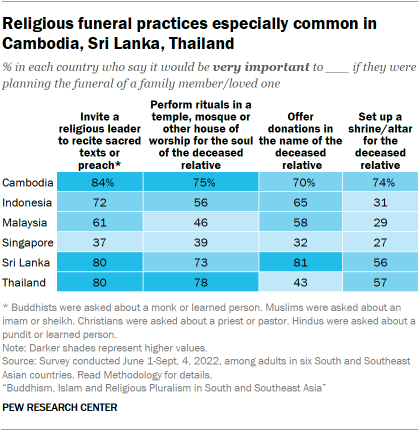

Rituals surrounding death are important to all the major religious groups in the countries surveyed.

For instance, most people in the Buddhist-majority countries of Cambodia (84%), Sri Lanka (80%) and Thailand (80%), as well as in Muslim-majority Indonesia (72%) and Malaysia (61%), say it would be very important to invite a religious leader to recite sacred texts or preach if they were planning the funeral of a family member or loved one.

Most people in the Buddhist-majority countries surveyed also say it would be very important to perform rituals for the relative in a temple or other house of worship, and to set up a shrine or altar for the deceased. Altars are especially valued by Buddhists in these countries: For example, 63% of Thai Buddhists say that setting up an altar would be very important, compared with just 6% of Thai Muslims who say the same about a shrine. Many people across religious groups also say it is very important to offer donations in the name of deceased relatives, including 71% of Christians in Indonesia, 61% of Muslims in Malaysia and 70% of Buddhists in Cambodia.

People in Singapore generally are less inclined than those in neighboring countries to say each of the four funerary rituals is very important, although more than half of Singaporeans say each ritual would be at least somewhat important if they were planning the funeral of a loved one.

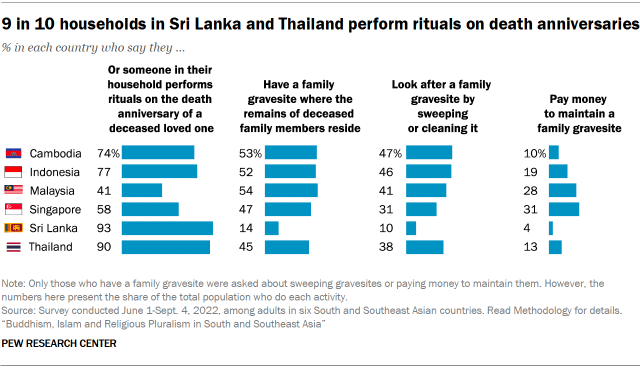

Across the countries surveyed, rituals surrounding deceased loved ones do not end after the funeral. Most people in five of the six surveyed countries (with the exception of Malaysia) say someone in their household performs rituals on the anniversary of the death of a loved one, including 93% in Sri Lanka and 90% in Thailand. This type of ritual crosses religious lines, with Sri Lanka as a prime example: Roughly eight-in-ten or more Buddhists, Muslims, Christians and Hindus in the country say someone in their household performs rituals on death anniversaries.

It also is fairly common across these countries to have a family gravesite where the remains of family members reside. Roughly half of respondents in five of the six surveyed countries (this time, with Sri Lanka as the exception) say this is the case. Among those who have a family gravesite, most people say they look after it by sweeping or cleaning it. It is generally less common for people to pay money to maintain a family gravesite.

By some measures, older adults are more religious than younger adults

Since this is the first time Pew Research Center has conducted an extensive, national survey on religion in most of these countries, opportunities for looking at how religious beliefs and practices are changing over time are limited. But differences between older and younger adults may provide clues into how each country is changing religiously.

In five of the six countries surveyed, nearly universal shares of both younger and older adults identify with a religion. Only in Singapore are younger adults (ages 18 to 34) slightly more likely than older adults to be religiously unaffiliated (26% vs. 20%).

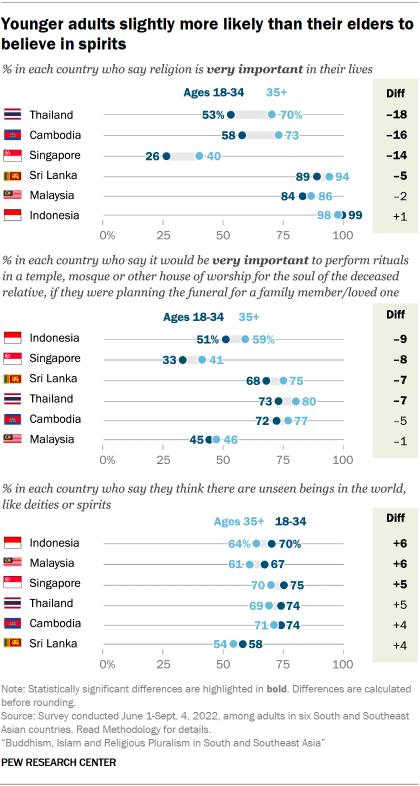

Across the countries surveyed, however, older adults are more likely than those ages 18 to 34 to be religious by a handful of standard measures – in line with the broad patterns seen in a 2018 Center analysis of the age gap in religiosity around the world.

For example, in Thailand, Cambodia, Singapore and Sri Lanka, people ages 35 and older are more likely than younger adults to say religion is very important in their lives. (This is not the case in the two Muslim-majority countries surveyed, where there is little difference on this measure between age groups.)

Across most of the countries surveyed, older adults also are generally more likely than younger adults to say various religious activities would be very important for a loved one’s funeral.

For instance, roughly four-in-ten older adults in Singapore say that if they were planning the funeral of a family member or loved one, it would be very important to perform rituals in a temple, mosque or other house of worship for the soul of the deceased relative. Just one-third of younger adults in Singapore say this.

Still, across many religious activities and beliefs, older and younger people are largely similar. For example, similar shares of older and younger adults in all six countries say they use special objects for blessings or protection.

Moreover, in a few countries, older adults (ages 35 and older) are slightly less likely than younger adults to say they believe in unseen beings, like deities or spirits. For instance, 61% of older Malaysians say they think there are unseen beings in the world, compared with 67% of younger adults in the same country.

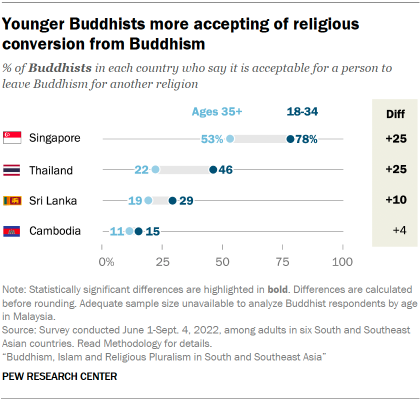

In several countries, younger Buddhist adults are more likely than older Buddhists to say it is acceptable for a person to leave Buddhism for another religion. For example, younger Thai Buddhists are twice as likely as those who are older to say that leaving Buddhism is acceptable (46% vs. 22%).

Among Muslims, only in Singapore are younger adults more likely than older Muslims to say it is acceptable to leave Islam for another religion (25% vs. 9%).

A theory in the social sciences hypothesizes that as countries advance economically and science takes a more prominent role in everyday life, populations tend to become less religious, often leading to wider social change. Known as “secularization theory,” it particularly reflects the experience of Western European countries from the end of World War II to the present, though it has its roots in earlier writings.

Recent academic research suggests that changes in religiosity stemming from economic development are more limited – tied to levels of religious identification or worship service attendance, rather than to the beliefs people hold – though others argue that secularization has increased dramatically in recent years. Pew Research Center’s previous work found only minimal support for secularization theory in India.

Data from Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia finds a bit of a mixed bag – some cases in which higher economic development seems to go hand in hand with less religion, but many others where there is no such correlation. For example, Singapore’s per capita gross domestic product (GDP) is about four times as large as any other surveyed country’s GDP, and it has by far the largest share of religiously unaffiliated individuals. Singapore also has the smallest share of adults who say religion is very important in their lives.

However, adults in Singapore are just as spiritual or religious as those in neighboring countries by other measures. For example, 87% of Singaporean adults say they believe in God or unseen beings – a higher share than in Cambodia (78%) or Thailand (81%). Meanwhile, nearly identical shares of Singaporeans (55%), Indonesians (55%) and Sri Lankans (54%) say that spells, curses or other magic can influence people’s lives.

Moreover, all six countries surveyed have experienced strong rates of economic growth over the last 30 years. Global per capita GDP in 2022 is almost triple what it was in 1990, but the six surveyed countries each have seen their per capita GDP grow at a faster rate, nearly quadrupling (or more) over the last three decades. Even with these rates of growth, very few adults (except in Singapore) identify as religiously unaffiliated today.

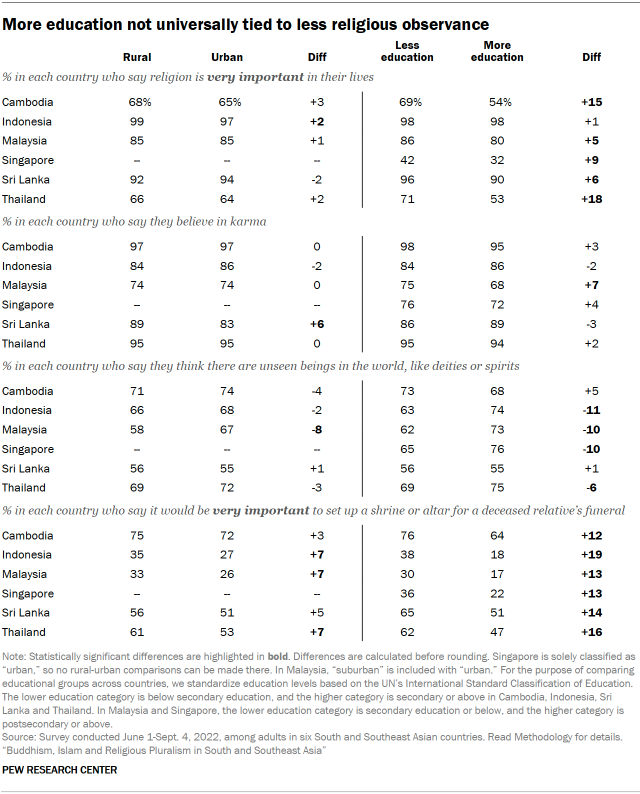

Those who live in urban settings are broadly as religious or spiritual as those in rural locations. In Malaysia, for instance, 74% of both urban and rural residents say they believe in karma. Rural people are slightly more likely than urban residents to follow a few funerary practices. In Indonesia, for example, 35% of rural residents say setting up a shrine is very important when planning a family member’s funeral, compared with 27% among urban Indonesians.

There is a somewhat stronger association between educational attainment and religion. Several measures of religious commitment are less common among people who have received more education. For example, Cambodians who have received at least a secondary education are less likely than other Cambodians to say religion is very important in their lives (54% vs. 69%) or to say a shrine would be very important for a deceased relative’s funeral (64% vs. 76%).

But, again, there are a number of beliefs and practices that do not show a pattern in which more education is associated with lower levels of belief. For instance, belief in karma is roughly the same within each country, no matter a person’s level of education. And people who have more education are more likely than other adults to say they think there are unseen beings in the world, like deities or spirits. In Singapore, for example, 76% of college-educated adults believe there are unseen beings, compared with 65% of other Singaporeans.

Share of Singaporeans identifying as Christian or unaffiliated is increasing

Singapore differs from the other countries surveyed in that it has no majority religion, and thus no single religion that is clearly associated with Singaporean national identity.

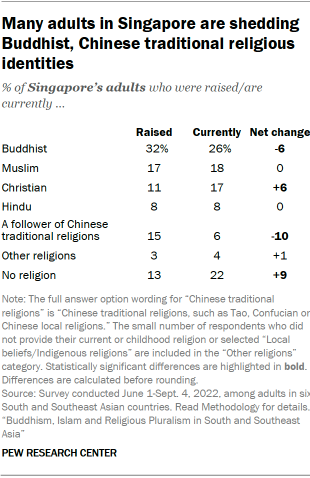

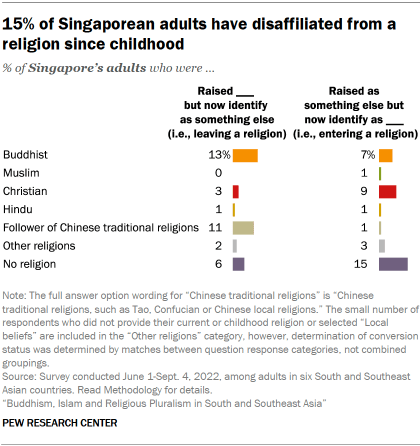

It also stands out in another way: While nearly all adults surveyed in the other countries still identify with the religion in which they were raised, far fewer Singaporeans do (64%). This “religious switching” has led to declines especially in the share of Singaporeans who identify as Buddhist or as followers of Chinese traditional religions, and to increasing shares who are Christian or religiously unaffiliated.

Among Singaporean adults, 32% say they were raised Buddhist, which is significantly more than the share who identify as Buddhist today (26%). The gap is even bigger when it comes to the share who identify with Chinese traditional religions, such as Taoism, Confucianism or Chinese local religions: 15% say they were raised in these traditions, while just 6% identify with Chinese traditional religions today.

By contrast, the share of Singaporeans who identify as Christian today is higher than the share who say they were raised Christian (17% vs. 11%). The same is true for adults in Singapore who do not identify with any religion: 22% of adults say they are religiously unaffiliated today, compared with 13% who say they were raised with no religion.

A similar pattern can be seen in Singapore’s census records over the last few decades. (Read “Singapore’s changing religious identity” for an analysis of this census data.)

Yet the story of religious change in Singapore is not simply that Buddhists and followers of Chinese traditional religions are leaving their childhood faiths for Christianity or to have no religious affiliation.

For instance, while 13% of Singapore’s adults were raised Buddhist but no longer identify as Buddhist, the share in the country who currently identify as Buddhist has decreased by only 6 percentage points because 7% of Singaporean adults converted into Buddhism (either from a different childhood religion or from no religion).

And while 15% of the country’s adult population has left behind a childhood religion to become religiously unaffiliated, the share of Singaporeans who identify with no religion has had a net increase of only 9 points, because 6% of the adult population has moved in the opposite direction: They are people who were raised without a religious affiliation but have since joined a religion (mostly Buddhism or Christianity).

While continued religious churn and other factors will also affect Singapore’s future religious composition, the way in which current parents say they are raising their children suggests that Buddhists may continue to decline as a share of the overall population.

Only two-thirds of Buddhist parents say they are raising their children as Buddhist; roughly one-quarter of Buddhist parents (27%) say their children are being raised with no religion. By contrast, much higher shares of Singapore’s Muslim (99%) and Christian (90%) parents say they are raising their children as Muslims and Christians, respectively. And the survey finds that 85% of religiously unaffiliated parents are raising their children without a religion.

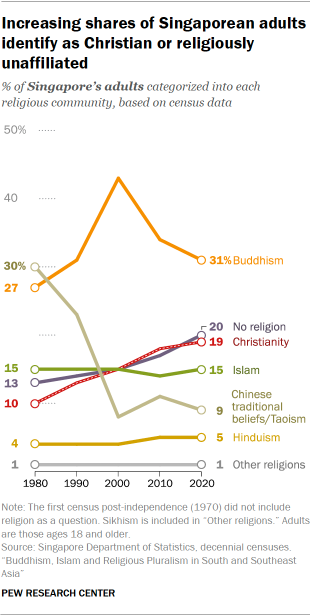

According to the national census, the religious makeup of Singapore today is markedly different from 40 years ago. Alongside rapid economic growth, the religiously unaffiliated have increased from 13% to 20% of the adult population. However, this period has also seen Christians roughly double as a share of the national population, from 10% in 1980 to 19% in 2020.

After increasing between 1980 and 2000 (from 27% to 43%), Singapore’s Buddhist population has since decreased to 1990 levels (31%).

Meanwhile, the share of Singapore’s adults who identify with Chinese traditional beliefs (including Taoism) decreased from 30% in 1980 to roughly one-in-ten in 2000 and generally has held steady since then.

Since 1980, the percentages of Singaporeans identifying as Muslim, Hindu and other religions have remained fairly steady.

Who are the people in Singapore who don’t identify with a religion, and what do they believe?

In stark contrast with neighboring populations in which nearly everyone claims a religious affiliation, roughly one-in-five Singaporeans do not identify with any religion – a group sometimes referred to as the “nones.” Singapore’s “nones” are overwhelmingly of Chinese descent and mostly college educated.

By some measures, Singapore’s religiously unaffiliated population does not appear very religious or spiritual. For instance, only 3% of the country’s “nones” say religion is very important in their lives, compared with 36% of Singaporean adults overall.

But as a group, Singapore’s religiously unaffiliated do not completely disavow religious or spiritual beliefs and practices. Nearly two-thirds of the “nones” (65%) say they think karma exists, and 43% say that a person can feel the presence of deceased family members – roughly comparable to the shares of Muslims (47%) and Christians (43%) in Singapore who say the same.

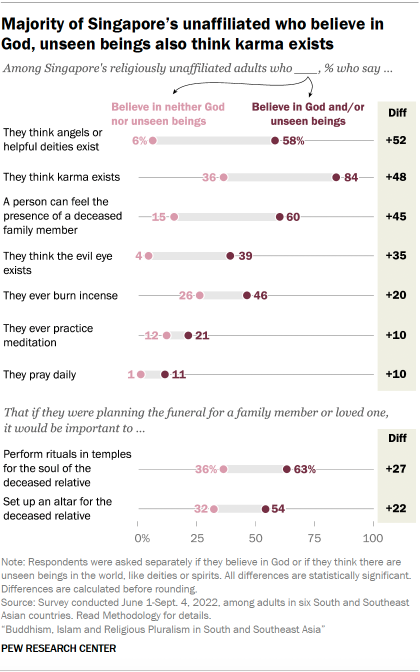

When asked about planning a funeral for a family member or loved one, many of Singapore’s religious “nones” also place importance on activities that could be considered spiritual or religious.

For example, 52% of those who claim no religion say it would be important to perform rituals in temples for the soul of the deceased relative, and 46% feel it would be important to set up an altar for the deceased relative.

Everyone who took the survey was asked whether they believe in God and, separately, whether they think there are unseen beings in the world, like deities or spirits.

About four-in-ten religiously unaffiliated Singaporeans (41%) say they believe in God, and a slim majority (56%) think there are unseen beings in the world. Roughly six-in-ten Singaporean “nones” (62%) hold at least one of these beliefs.

“Nones” who are women are more likely than religiously unaffiliated men to believe in God and/or unseen beings (68% vs. 57%). Also, Singaporeans who were raised in a religion but are unaffiliated as adults are more likely to believe in God or unseen beings (66%) than Singaporeans who were raised with no religious affiliation and are still “nones” today (52%).

By nearly every measure included in the survey, the religiously unaffiliated who say they believe in God and/or unseen beings (“believing nones”) are more likely than other “nones” to connect with spiritual and religious concepts. For instance, the vast majority of “believing nones” also think karma exists (84%), but only 36% of Singapore’s other “nones” believe in karma. And the religiously unaffiliated who believe in God and/or unseen beings are much more likely than others to say that it would be important to perform rituals in temples for the soul of the deceased relative when planning a funeral (63% vs. 36%).

How those who link religious and national identities differ from others

Some regional scholars have noted increasing support for nationalistic movements centered on each country’s majority religion.

As explained above, many members of the religious majority in each country (Buddhists in Cambodia, Sri Lanka and Thailand, as well as Muslims in Indonesia and Malaysia) say it is very important to be a member of their religious group to truly share their national identity. Many also say they want their society’s laws to be based on their religion’s teachings.

People who take one of these positions are especially likely to take the other. And those who express both views are referred to in this section as “religion-state integrationists.” (Broadly, religion-state integration can be understood as the opposite of “separation of church and state,” the principle that the power of the state should not be used to coerce or promote religion, which is legally or traditionally followed in the United States and some other countries.)

A majority of Muslims in Indonesia (57%) and Malaysia (69%) are religion-state integrationists, as are most Buddhists in Sri Lanka (72%) and Cambodia (75%). A sizable minority of Thai Buddhists (45%) also fall into this category.

‘Religion-state integrationists’ are especially religious

Religion-state integrationists stand out from other members of their religious communities in a variety of ways.

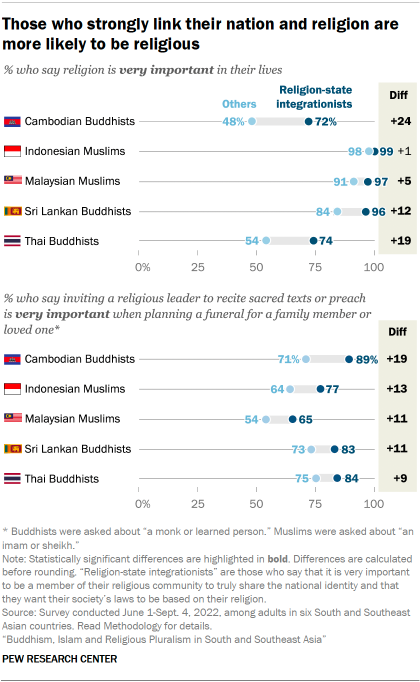

While the region overall is very religious, religion-state integrationists generally are even more religious than other people, across a host of measures.

Among Cambodian Buddhists, for example, those who say both that it is very important to be Buddhist to be truly Cambodian and that Cambodian law should be based on Buddhist dharma are much more likely than other Buddhists to say religion is very important in their lives (72% vs. 48%).

Attitudes relating to funerals show a similar divide. For instance, about three-quarters of religion-state integrationists in Indonesia’s Muslim community say inviting an imam or sheikh to recite sacred texts or preach is very important when planning a family member’s funeral, compared with roughly two-thirds of other Muslims in the country (77% vs. 64%).

(For more on this region’s general levels of religiosity, including among minority communities, read Chapter 3 and Chapter 4. For more on funeral practices, refer to Chapter 5.)

Religion-state integrationists also are:

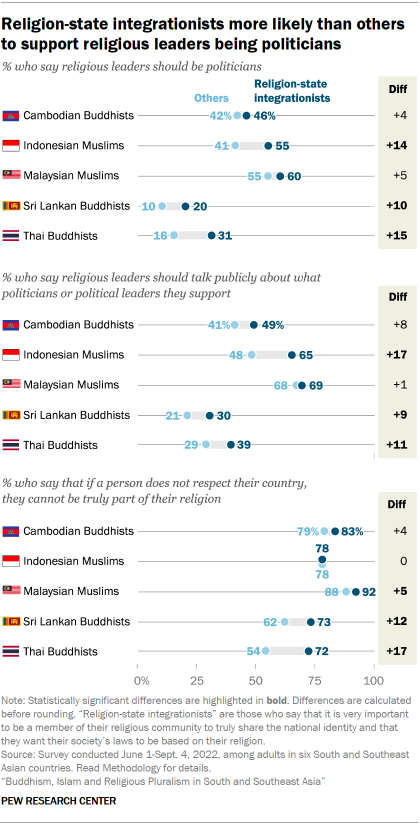

- More likely than other Buddhists or Muslims in their countries to support religious leaders’ involvement in politics.

- Less likely to want neighbors from minority religions.

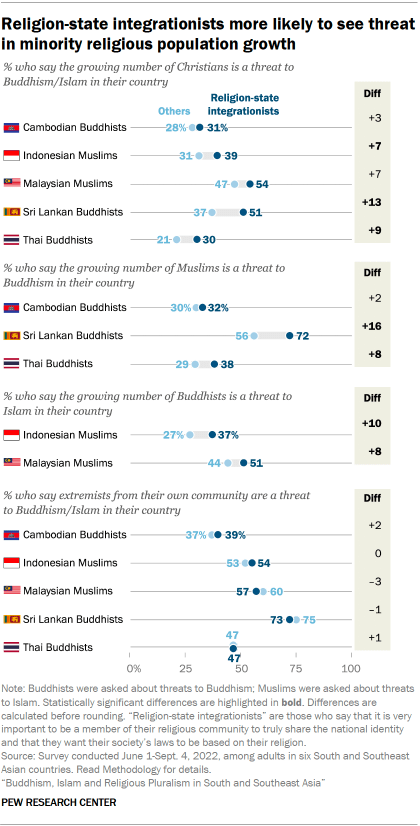

- Slightly more likely to see threats to their religion from minority religious communities.

These relationships generally hold even when controlling for other factors, such as level of personal religiosity, age, gender and education. In other words, correlations between views on the relationship between religion and state and opinions on these other issues exist above and beyond the fact that religion-state integrationists are more religious. Cambodia’s religion-state integrationists sometimes defy the patterns seen across the other four surveyed countries.

Religion in politics

As one might expect, religion-state integrationists are somewhat more likely than others in their communities to support religious leaders’ direct involvement in politics.

In Thailand, for instance, Buddhists who link Buddhist and Thai identities and say Thai law should be based on Buddhist dharma are roughly twice as likely as other Buddhists to say religious leaders should be politicians (31% vs. 16%).

Even among Buddhist religion-state integrationists, however, around half or fewer say religious leaders should be politicians, talk publicly about the politicians they support, or participate in political protests. Muslims in Indonesia and Malaysia are more inclined to favor religious leaders’ involvement in the political sphere.

Members of the majority religious community who strongly link their religion with the national identity also are more likely than others to say that disrespecting their country disqualifies someone from being truly part of their religion. Among Sri Lankan Buddhists, 73% of religion-state integrationists say that if a person does not respect Sri Lanka, they cannot be truly Buddhist – significantly more than the share of other Sri Lankan Buddhists who say disrespecting Sri Lanka disqualifies someone from being Buddhist (62%).

(For more on the role of religious leaders in politics, read Chapter 7. For more on what activities would disqualify someone from being part of a religious community, refer to Chapter 2.)

Views toward minority religions

Buddhist nationalism has been linked with antagonism and violence between Buddhists and religious minorities in countries dominated by Theravada Buddhism, including during the Sri Lankan civil war. Similarly, some scholars have asserted that there is a connection between rising “religious nationalism” and xenophobia in Muslim-majority Indonesia.

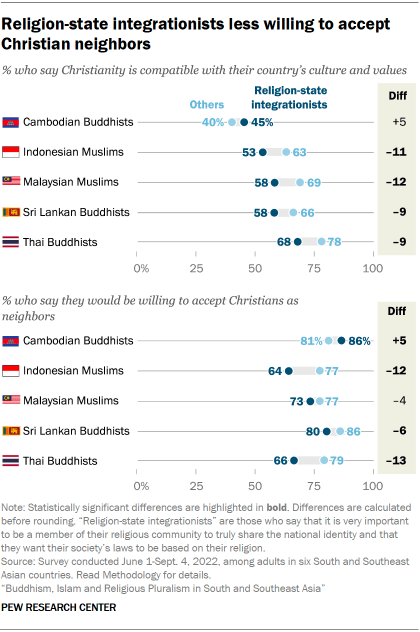

In general, people who say that it is very important to be a member of their religious community to truly share the national identity and that they want their society’s laws to be based on their religion are less likely to see other religions as compatible with their country’s culture and values. They are also less likely to accept followers of other religions as neighbors – although most religion-state integrationists say they would be willing to accept people from other religions as neighbors.

For example, among Indonesian Muslims, religion-state integrationists are less likely than other Muslims to say Christianity is compatible with Indonesian culture and values (53% vs. 63%) or to say they would accept Christians as neighbors (64% vs. 77%). This pattern broadly holds when asking about other religious communities, such as Hindus and followers of Chinese traditional religions.

However, Cambodian Buddhists stand out. There are no significant differences between religion-state integrationists and other Buddhists in Cambodia on any questions about the compatibility of other religions with Cambodia’s culture and values or potential neighbors.

(For more on attitudes toward other religious groups across the surveyed countries, read Chapter 6.)

Those who link religion and national identity and say their national laws should be based on religion are slightly more likely to say that the growing numbers of various religious minorities are a threat to Buddhism or Islam in their country.

For instance, three-in-ten Thai Buddhists who are religion-state integrationists say the growing number of Christians in Thailand is a threat to Thai Buddhism – more than the 21% of other Thai Buddhists who voice this opinion.

(These questions were designed to gauge demographic anxieties, regardless of whether or not these minority populations are actually growing within the countries surveyed.)

In general, religion-state integrationists also are somewhat more likely than other Buddhists or Muslims to say that tourists from other countries and the influence of China are threats to Buddhism and Islam in their country. However, they are no more likely to see extremists from their own community as a threat to Buddhism or Islam in their country. Among Sri Lanka’s Buddhists, for example, roughly three-quarters of both religion-state integrationists and others say that Buddhist extremists are a threat to Buddhism in Sri Lanka (73% and 75%, respectively).

Similarly, there is generally no difference between the groups within a country when asked whether the influence of the United States is a threat.

As with other topics, there are no significant differences on perceived threats to Buddhism in Cambodia between Buddhists who do or do not classify as religion-state integrationists. (For more on attitudes about perceived threats to Buddhism and Islam, refer to Chapter 6.)