Content note: this article mentions genocide and acts of colonial violence against Aboriginal people.

How long do you think stories can be passed down, generation to generation?

Hundreds of years? Thousands?

Today, we publish new research in the Journal of Archaeological Science demonstrating that traditional stories from Tasmania have been passed down for more than 12,000 years. And we use multiple lines of evidence to show it.

Read more:

The Memory Code: how oral cultures memorise so much information

Tasmania’s violent colonial history

Within months of establishing a colonial outpost on the island in 1803, British officials had committed several acts of genocide against Aboriginal Tasmanian (Palawa) people. By the mid-1820s, soldiers, convicts, and free settlers had taken up arms to fight what became known as the “Black War”, aimed at capturing or killing Palawa and dispossessing them of their Country.

Tasmania’s colonial government appointed George Augustus Robinson to “conciliate” with the Palawa. From 1829 to 1835, Robinson travelled with a small group of Palawa, including Trukanini and her husband, Wurati. By 1832, Robinson’s “friendly mission” had turned to forced removals.

State Library of Victoria

Read more:

Coming to terms with Tasmania’s forgotten war

Robinson kept a daily journal, which included records of Palawa languages and traditions. Over time, Palawa men and women slowly began to share some of their knowledge, explaining how their ancestors came to Tasmania (Lutruwita) by land from the far north, before the sea formed and turned their home into an island. They also spoke about the Sun-man, the Moon-woman, and a bright southern star.

These stories are of immense importance to today’s Palawa families who survived the devastating impact of colonisation, and who continue to share these unique creation stories. Through careful investigation of colonial records, and collaborating with Palawa knowledge-holders, we found something remarkable.

Rising seas and the formation of Lutruwita

Over the past 65,000 years, Australia’s First Peoples witnessed natural disasters and significant changes to the land, sea and sky. Volcanoes spewed fire, earthquakes shook the land, tsunamis inundated the coastlines, droughts plagued the continent, meteorites fell to the earth, and the stars shifted in the night sky.

Some 20,000 years ago, the world was in the grip of an ice age. Australia was conspicuously drier than it is today, and the ocean was significantly lower. All of that sea water was bound up in glaciers that swathed vast tracts of land, particularly across the Northern Hemisphere, and polar ice caps much larger than ours today.

As time passed, temperatures gradually rose and the ice began to melt. After 10,000 years, the sea level had risen 125 metres; a process that dramatically transformed coastlines and submerged landscapes that had been ancestral Country for thousands of generations. This forced humans to change where and how they lived.

Read more:

Ancient Aboriginal stories preserve history of a rise in sea level

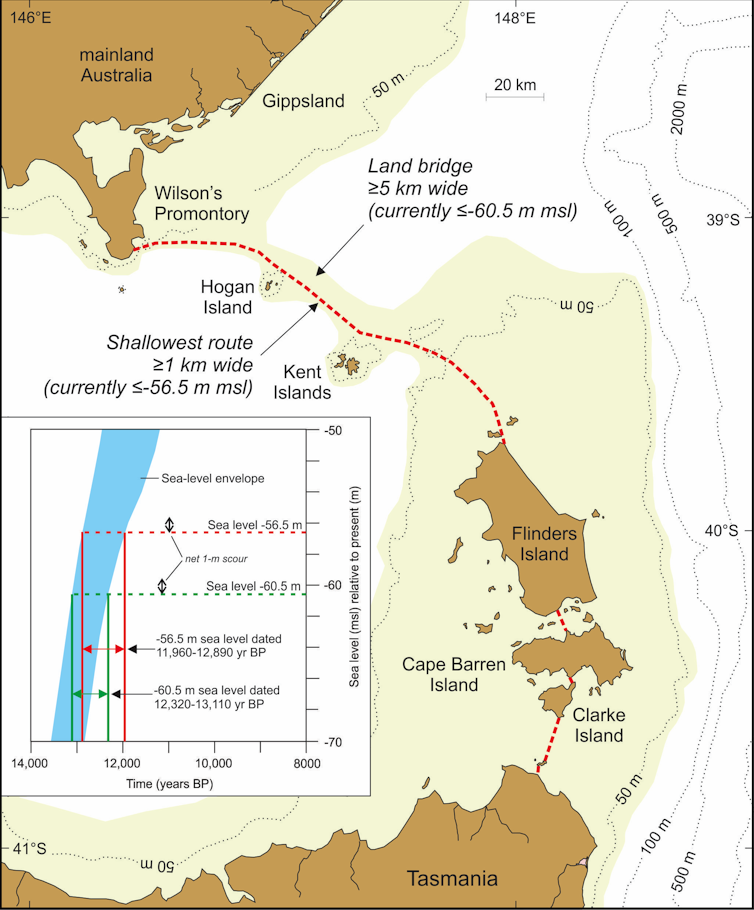

During the ice age, both Lutruwita and Papua New Guinea were connected to mainland Australia by dry land, forming a landmass called Sahul. As the seas rose, Tasmania’s connection gradually narrowed to form what geologists call the Bassian Land Bridge.

Patrick Nunn, Author provided

People continued to live on this “land bridge”, but by 12,700 years ago it had narrowed to just 5 kilometres wide (lime-green shading on the map above). Habitable land was gradually reduced as the sea closed in. Less than 300 years later, the “land bridge” was gone and Lutruwita was completely surrounded by water.

Palawa traditions from that time survived hundreds of generations of retelling, forming part of a larger canon of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander stories around Australia. They described rising seas and submerging coastlines as the ice sheets melted before levelling off around 7,000 years ago. Stories of similar antiquity are known from other parts of the world.

Read more:

Ancient Aboriginal stories preserve history of a rise in sea level

A great south star

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures developed rich and complex knowledge systems about the stars, which are still used today. They describe the movements of the Sun, Moon, and stars, as well as rare cosmic events, such as eclipses, supernovae, and meteorite impacts.

In the 1830s, a Palawa Elder spoke about a time when the star Moinee was near the south celestial pole. He laid down a pair of spears in the sand and drew a few reference stars to triangulate its position.

Read more:

Stories from the sky: astronomy in Indigenous knowledge

Colonists seemed perplexed about the presence of an antipodean counterpart to Polaris, as no southern pole star exists today. Some tried to identify the stars on the star map, but seemed confused and labelled them incorrectly, as they were unaware of an important astronomical process called axial precession.

As the Earth rotates, it wobbles on its axis like a spinning top. This shifts the location of the celestial poles, tracing out a large circle every 26,000 years. As thousands of years pass by, the positions of the stars in the sky slowly change.

Read more:

Stars that vary in brightness shine in the oral traditions of Aboriginal Australians

Long ago, Canopus was at its southernmost point in the sky. Lying just over 10 degrees from the south celestial pole, it appeared to always hover in the southern skies each night. That last occurred 14,000 years ago, before rising seas turned Lutruwita into an island.

Stellarium, CC BY

Exciting collaborative futures

We can see through independent lines of evidence that Palawa stories have been passed down for more than twelve millennia. We also find here the only example in the world of an oral tradition describing a star’s position as it would have appeared in the sky over 10,000 years ago.

Our investigation of colonial records that record traditional systems of knowledge has demonstrated a powerful cross-cultural way of better understanding deep human history. This also recognises the immense value of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander traditions today.

This research was co-authored by graduate Michelle Gantevoort from RMIT University, and student researchers Ka Hei Andrew Law from the University of Melbourne and Mel Miles from Swinburne University of Technology.