It’s 2014, her senior year of college. Stephanie Land, bestselling author of Maid, is almost 35, still two years away from landing the publishing deal that will change her life.

A single parent of a six-year-old, she gulps coffee from an empty peanut-butter jar in college classes and struggles to stay awake after kindergarten drop-off. Before the year is out, she’ll be pregnant again, her circumstances infinitely harder.

Land’s mind is always somewhere else. Rent. Bills. Groceries. Medicine, if the budget will stretch that far. An abusive ex-partner who’s stingy with child support.

“It’s pretty relentless”, a college professor remarks dismissively in the feedback on one of Land’s life-writing assignments, a quibble that “throbs” in the aspiring author’s head for days afterwards.

My life may be relentless, she later writes in one of her many notebooks, but goddammit so am I.

So the days and weeks unfold in Land’s second memoir, Class, an insular but vivid reflection on a tertiary education system that seems to sabotage the very students who work hardest to be there.

Review: Class – Stephanie Land (Atria)

“Of all the things in my life that I didn’t have access to or felt like I didn’t deserve for some reason, an education hadn’t crossed my mind as a thing I wasn’t supposed to have,” Land recalls.

Yet getting an English degree while struggling to put food on the table leaves Land frequently wracked with guilt, a “constant, crushing panic”.

Pressing towards graduation, often on the brink of physical exhaustion, she reflects bitterly on the administrative hoop-jumping required of students with little financial or social support, striking at the corporatised core of higher education in America:

I had forgotten the part of the game where no one’s education mattered more than the money the university could make from your opportunity to soak up all that learning. God forbid they would make it affordable or easy.

The years she spends in snowy Missoula, Montana, are not just plagued by hunger in the literal sense. They are propelled by it too. She hankers for the respite of an easier life: financial security, reliable child care and possible entry to an MFA program.

But even as the book’s titular play on words conjures both the experience of class immobility and the college classroom Land sets out to critique, the book ends up being about neither in particular. As a sequel of sorts to Land’s celebrated debut, Class lacks the sustained storytelling that helped establish Land as an unflinching class commentator.

Maid makes unexpected connections to the privilege and plight of America’s precarious middle class – afforded by the author’s invisible but intimate presence in the homes she cleans. But Class turns inwards, often as disconnected and unfocused as the year it documents.

As one Goodreads reviewer has commented, Class falters in its telling, feeling more like “a recitation of things that happened” than the feat of “unfussy prose and clear voice” that glues Maid together.

“Not much actually happens in ‘Maid’,” Jenny Rogers commented in The Washington Post. Yet it “holds you”.

If Class has a looser grip, what else does it offer readers?

Barbara Ehrenreich never stopped trying to change the world

Mega-success with Maid

If yours was one of the 67 million households that tuned into Maid on Netflix, you may be more familiar with Margaret Qualley’s “Alex”, loosely based on Land, whose unplanned pregnancy and subsequent attempts to make it alone push her below the poverty line and into the houses of wealthier people whose toilets she scrubs.

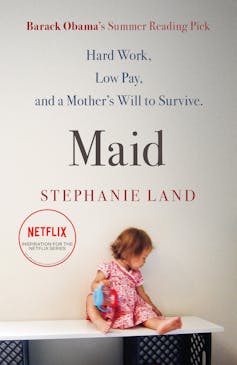

Published at the beginning of 2019, Maid launched at number three on The New York Times Best Seller list and was praised by Time magazine as “an empathetic portrait of poverty that dispels the myth of bootstrapping”. Former US President Obama handpicked it for his summer reading list later that year.

And in 2021, Netflix’s ten-episode limited series based on the book was a commercial and critical success, laying bare what Lucy Mangan has rightly called the “unflinching anatomisation of the red tape that surrounds every effort to access the (already minimal) help supposedly on offer to desperate women and their children”.

Class picks up where Maid leaves off.

In the acknowledgements pages, Land describes a sense of responsibility to her readers to continue the story she’d so far “only partly told”. She insists it’s the book she always wanted to write, focusing on her “hungriest year” – when her “stomach and brain lived in a constant state of anger and lightheadedness”.

‘I just go to school with no food’ – why Australia must tackle child poverty to improve educational outcomes

‘Easily’ reliving imposter syndrome

To anyone who’s experienced persistent poverty, generational trauma or the vagaries of solo parenting firsthand, the pervasive themes of frustration and despair that reappear in Class will remain uncomfortably close.

When Land looks down at her faded clothes and feels like “she always had on the first day of school: a nerdy new kid who didn’t know what to wear in order to fit in”, I can easily relive the imposter syndrome that haunted my own academic journey from start to finish.

The first in my working-class family to complete a university degree, I subsisted on a budget of only $200 a week when I first moved to Brisbane to complete my bachelor’s degree. Ten years later, after bouncing in and out of hospital with life-threatening depression, I was left to pay off thousands in medical debt through my PhD stipend and casual university teaching.

But no matter their background, I suspect few readers could come away from Class without a sharp sense of the unremitting fatigue, frequent indignities and “bleak mental arithmetic” striving to stay afloat demands of the economically disadvantaged.

In Class, Land continues to keep “obsessive track” of her bank account. She pockets toilet rolls from public bathrooms and carries a list of fixed expenses and estimated income with her wherever she goes.

“All my school notebooks had these tiny budgets written inside,” she writes. They’re taped to the wall beside her desk; she scribbles “different versions of it” in her day planner at the start of each month. A tangle of upbeat acronyms – sources of financial assistance like FAFSA, TANF, SNAP – represent a demoralising bureaucratic burden for little ultimate gain.

Perhaps surprisingly, though, Class is strongest when Land allows herself to drift into a more digressive mode. Her commentary on contraceptive choices, for example, is far more interesting and well developed than the diarised recollections she shares in the lead-up to discovering her second unplanned pregnancy.

Partway through the book, she recalls a time when Missoula was labelled the “rape capital” of America after a number of University of Montana football stars were accused of sexual assault. Curiously, she mentions only in passing that a flurry of letters to the editor in response to the news helped her recognise her own experiences of rape.

Where are the most disadvantaged parts of Australia? New research shows it’s not just income that matters

Missed opportunities

In this way, Class sometimes feels like a series of missed opportunities in the plotting, pace and development of what’s otherwise a compelling premise and an evocative setting. Land writes with an explicit distaste for having to justify or explain herself. She openly objects to the expectation (and veneration) of resilience or “success stories” in the face of gross inequity.

But in Class, this resistance often translates as an unsatisfying emotional distance.

In Maid, where Land speaks of the startling imprint of cleaning other people’s houses on her life – the vulnerabilities she’s exposed to “somehow reminding of her own” – we’re generously treated to what renowned memoirist Mary Karr calls the “totemic objects”, or the idiosyncratic details, that sophisticated writers strive to “place on every page”. The minutiae of her life — and those hers overlaps — feel real in the pungent whiff of her sick daughter’s breath, a client’s hidden cigarette stash, the flecks of vomit on an upturned toilet seat.

Class carries a greater sense of urgency, resorting to a more fervid yet mechanical style that belies its byline as a rumination on motherhood, hunger and higher education.

Land alludes to white privilege only once, commenting that her “plain” appearance has allowed her “an occasional break from my poverty, at least in terms of its visibility to others”. Of class hierarchies, she remarks fleetingly that “what society encouraged and what it actually supported were two different things depending on what economic class you found yourself in”.

Critical engagement with the intersections between identity and the ways we experience the world is noticeably absent. As a writer who labours to reveal the bergs of difficulty that may lurk beneath the appearance of success or stability, she is not always willing to excavate those depths outside her own immediate experience.

In a telling aside that mirrors the book’s inward focus, she exposes a habitual impulse for assuming her circumstances are exceptional, rarely interested enough to look deeper:

My friendships were surface level only. Not because I necessarily wanted it that way. I just didn’t have much to give back. There was so much going on in my life between work, kid, and school that I didn’t have the bandwidth to sit and listen while someone talked to me about struggles they had. When I confessed this to anyone, they invariably said that friendship was a two-way street, a give-and-take, where one person needs more support and then the other might and so on. “Yeah, but I don’t know if I will ever not need more support,” I would say.

Most baffling is Land’s treatment of her thwarted dream of enrolling in a Masters of Fine Arts (one of few anchoring elements of the narrative), when an unsympathetic college professor denies her application: “Babies don’t belong in grad school”. It’s a gut-wrenching disappointment Land brushes aside in less than a page.

Even America’s increasingly decentralised higher education system goes largely unexplained and unexamined, in a story the publisher packages as a “searing indictment”.

Class is an emptier book, hungry for the reservoir of rich episodic detail that spurred Maid to its unprecedented success as both a memoir and a televised adaptation.

Friday essay: single parenting with a disability – how my 9-year-old daughter became my carer in shining armour

Like its author, ‘Class works hard’

Maid, however, was always going to be a tough first act to follow. The so-called “sophomore slump” (or, second-book syndrome) is a recognised phenomenon in the most ordinary of circumstances. An author whose debut has achieved bestseller status and been adapted to the screen invites inevitable comparison.

Even so, Class makes up for what it lacks in craft in its simple insistence on being heard.

Reflecting on her interactions with readers, Land explains that people often ask what motivated her to write about her own life. “The answer is both lofty and painfully basic,” she reveals at the back of Class:

On the one hand, I wanted to dismantle stigmas surrounding single moms, especially those who parent under the poverty line. On the other, I needed the money. The prospect of publishing a book wasn’t just the answer to a lifelong dream – it was the discovery of a life raft on a sinking ship.

For readers like me, who’ve floated adrift on their own sinking ships, Class may well be a life raft of another kind. Land’s relentlessness – and her strident aversion to inspirational gloss-coating – creates a redemptive space for lives messily lived, intrusively bureaucratised, and unfairly judged.

At a time when the prohibitive cost of higher education deters so many from the liberal arts (in Land’s America, but also Australia and elsewhere around the world), her story stands as an imperfect but powerful reminder that all voices matter.

Storytelling, Land reminds us, can serve a variety of purposes, discouraging silos of silence from expanding around experiences of marginalisation and expressions of outrage.

Much like Land herself, Class works hard.

It doesn’t always get where it wants to go, but there’s value in its effort.