How many times have you come out of the cinema and heard someone snidely remark they preferred the book, as though this somehow connects them to a richer, more highbrow tradition?

This might ring true when it comes to literary masterworks like F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, adapted into two so-so versions nearly four decades apart (equally dull, for almost opposite reasons). But the reverse is often the case with popular fiction, which benefits from the immersive, visceral quality of the cinema.

Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel Jaws, which turns 50 this year, was a smash. Despite critics’ reservations, it was on the New York Times bestseller list for 44 weeks. Yet when we think of Jaws, images from Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film adaptation are what come to mind – along with John Williams’ iconic theme music.

Spielberg’s Jaws keeps the simple – and stunning – narrative architecture of Benchley’s novel intact. A shark terrorises a small beach community that depends on wealthy tourists for sustenance. Brody, the chief of police, keeps the beaches open due to political pressure from Mayor Vaughan; when more attacks occur, marine biologist Matt Hooper comes to help. Together, they contract wild shark hunter Quint to help them kill the great white.

But the tone of grand adventure that defines Spielberg’s film marks a major departure from the novel. In Benchley’s work, more energy is directed towards exploring the minor social and political lives of its small-town denizens than in staging an epic showdown between man and beast – and, crucially, it differs radically from the film in its characterisation. In Spielberg’s world, the main characters are likeable, heroic, whereas in the novel they’re petty, broken and bitter, wading through the messes their personal lives have become.

These differences are not simply evidence of a young director’s desire to make the material his own. They map the changing consciousness of American popular culture in the 1970s, from a resolute focus on the violence simmering within United States society and policy (the civil rights movement and the Vietnam War) to an attempt to forget about these things through spectacular, anodyne entertainment.

As we know, Spielberg’s film reshaped Hollywood, virtually single-handedly inventing the “blockbuster” and marking a significant shift away from the existentially charged, sometimes nihilistic, ever self-critical films of the previous decade or so.

Yet the two dominant themes situating Benchley’s novel in a rich American literary tradition also underpin the film: its biting look at small-town politics and economics, and its reverent study of a wilderness awesome and sublime.

Mark Sullivan/Getty Images

From Jaws to Star Wars to Harry Potter: John Williams, 90 today, is our greatest living composer

‘The shark material is brilliant’

At the novel’s core is a swift, economically told tale of human versus beast: a classic American adventure in the vein of Jack London’s White Fang or Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick.

Benchley punctuates this drama with a keen interrogation of the social dynamics of small American communities in the context of the economic pressures of capitalism.

A career journalist, Benchley is effective in describing actions, events and scenery: shark hunting, the ocean, Quint’s boat. The shark material is brilliant – the few times it cuts to the shark’s point of view (recalling Spielberg’s redeployment of the creature’s point of view from Creature from the Black Lagoon), the writing becomes electric, effortless. Benchley is at his best when describing the movements of the shark in the water.

For example, when Hooper is cage diving, towards the end of the novel:

The head was only a few feet from the cage when the fish turned and began to pass before Hooper’s eyes – casually, as if in proud display of its incalculable mass and power. The snout passed first, then the jaw, slack and smiling, armed with row upon row of serrate triangles. And then the black, fathomless eye, seemingly riveted upon him. The gills rippled – bloodless wounds in the steely skin.

But the material about people is less confident – the writing is uneven and trite in places, with moments between characters sometimes strained in order to generate the necessary action.

This includes two subplots Spielberg and team wisely cut from the film.

The first involves a murky connection between Mayor Vaughn and the Mob that is partly responsible for his desire to keep the beaches open, despite Brody’s warnings. It seems both underdeveloped – we don’t find out much about it – and strangely present, with the majority of the novel’s scenes involving the mayor gesturing towards it.

The second, which probably would have been fatal to the film, involves an affair between Brody’s wife Ellen and Matt Hooper.

Guide to the classics: Moby-Dick, by Herman Melville

Characters ‘loathsome in places’

One of the great joys of the film is the developing friendship between Hooper and Brody, culminating in their delightful final exchange. After the shark is dead and they are kicking their way back to shore, Brody laughs: “I used to hate the water.” Hooper replies, “I can’t imagine why”. Both men are happy to have survived, and to have each other.

In the novel, it’s more or less hate at first sight, with Brody immediately resenting Hooper because he grew up as a “summer person” in the area. Brody is ashamed he’s not one of the wealthy summer people, and tries to hide this through a kind of pathetic machismo, which emerges most visibly in his competitiveness with Hooper.

This obsession with summer people defines much of the dialogue between Brody and Ellen, with Brody’s resentment of the summer people’s nonchalant and emasculating wealth matched by Ellen’s resentment of the fact she used to be a summer person before she married this oaf of a police chief.

The characters in the novel are thus thoroughly unappealing – even loathsome in places. Spielberg famously stated the shark was his favourite character in the novel.

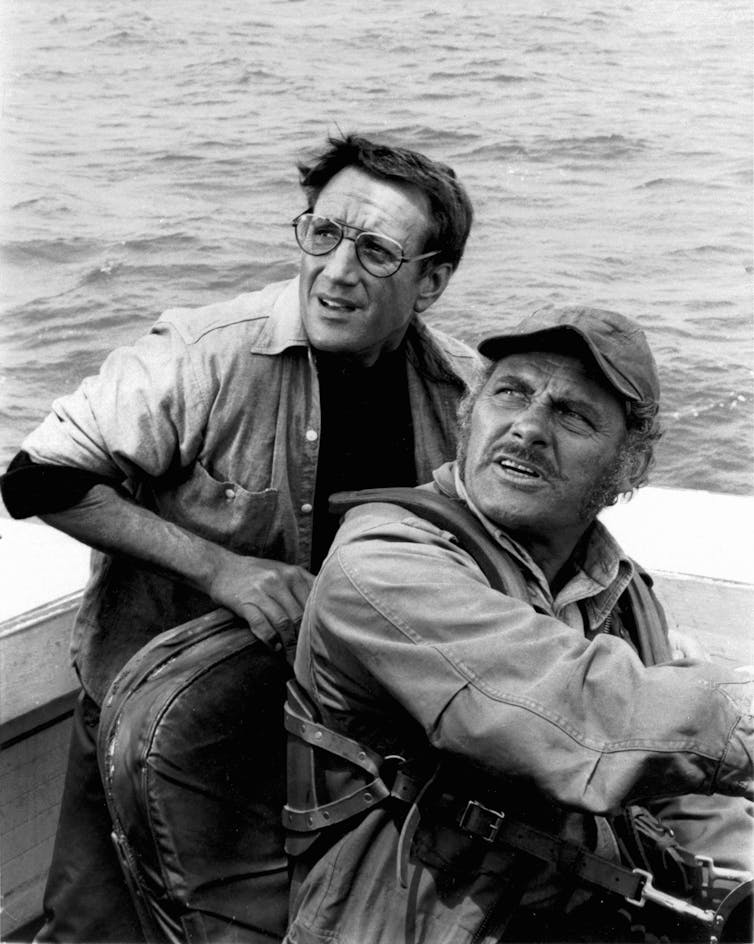

The film’s Brody, anchored by the effortless charisma of Roy Scheider, is a steadfast, stoic working man who loves his wife and children and isn’t ashamed to show it in a gentle, unassuming way.

In the novel, Brody is “jealous and injured, inadequate and outraged”, a chauvinistic beer-guzzling bully, an obsessive – and often self-loathing – jerk. One of our first forays into his consciousness makes this immediately apparent:

Sometimes during the summer, Brody would catch himself gazing with idle lust at one of the young, long-legged girls who pranced around town – their untethered breasts bouncing beneath the thinnest of cotton jerseys. But he never enjoyed the sensation, for it always made him wonder whether Ellen felt the same stirring when she looked at the tanned, slim young men who so perfectly complemented the long-legged girls.

Ellen is also much less sympathetic in the novel (though admittedly in the film she’s a cardboard cutout of virtuous motherhood and wifedom).

She moves around as a shell of a person, a terrible snob disappointed by her social status and too embarrassed and ashamed to do anything about it, “tortured by thoughts she didn’t want to think – thoughts of chances missed and lives that could have been”. Like Brody, she is drowning in self-loathing:

She made sure that everyone she met knew she had started her Amity life on an entirely different plane. She was aware of what she was doing, and she hated herself for it, because in fact she loved her husband deeply, adored her children, and – for most of the year – was quite content with her lot.

The Hooper of the novel is similarly transformed by the film from an arrogant show-off, vaingloriously pursuing fame as a scientist at the expense of everything else, into a smart, responsible and energetic ball of fun, fully embodied by dynamo actor Richard Dreyfuss.

Only Quint – the mythical, Ahab-esque hunter (“Brody saw fever in Quint’s face – a heat that lit up his dark eyes, an intensity that drew his lips back from his teeth in a crooked smile”) – remains fundamentally unchanged, even though his unyielding brutality seems more appealing in the novel than in the film, with Robert Shaw portraying him as an antisocial maniac.

Universal Pictures/AAP

This revision includes the whole dynamic of the Brody family. The delightful moments between the kids and their parents, reflecting Spielberg’s superpower as a director (his talent for bringing sentimental family moments to life), are absent from the novel.

There’s something depressing about Brody’s relationship with his family. He has virtually no interaction with his children, and when he does, it’s like this:

The oldest boy, Billy, lay on the couch, leaning on an elbow. Martin, the middle son, age twelve, lounged in an easy chair, his shoeless feet propped up on the coffee table. Eight-year-old Sean sat on the floor, his back against the couch, stroking a cat in his lap. “How goes it?” said Brody. “Good, Dad,” said Bill, without shifting his gaze from the television.

Is ‘easy to swallow’ better?

Of course, populating a novel with unlikable characters and depressing family scenes is not a problem in and of itself. Popeye from William Faulkner’s Sanctuary is hardly likeable, neither is pompous Nick Carraway from The Great Gatsby – and you’d be hard pressed to find a Dickens novel that doesn’t feature some degree of family strife.

But in Jaws, a “man versus beast” tale, a melodramatic thriller, it creates a flat feeling: we don’t wholly mind the prospect of these characters being eaten by a shark. At the same time, Benchley – despite occasional flaws in the writing – does capture something of the dismal inconsistencies and banalities of being human. The complex self-loathing of the characters contrasts with the brutal and unthinking power – the genius for action and killing – of the shark.

The film redacts the frailties and faults of the characters, turning an adult (albeit imperfect) novel into family-friendly fodder. Spielberg took a low-key thriller doubling as a study of a small American community and turned it into the kind of blockbuster that would get people back into – and keep them in – cinemas.

It comes as no surprise that the film also excises much of the novel’s pointed class critique. Note, for example, this description of the summer people early in the book, the haves to the local have-nots:

Privilege had been bred into them with genetic certainty. As their eyes were blue or brown, so their tastes and consciences were determined by other generations. They had no vitamin deficiencies, no sickle-cell anaemia. […] Their bodies were lean, their muscles toned by boxing lessons at age nine, riding lessons at twelve, and tennis lessons ever since. They had no body odour. When they sweated, the girls smelled faintly of perfume; the boys smelled simply clean.

Most, I’m sure, would hold the novel up as an inferior work. At a technical level, they’d probably be right. But while it’s pretentious, it’s also much more ambitious than the film.

Is something easy to swallow necessarily better for the digestion? Only a shark could answer that. The novel is ugly in places. But where it works, it works at the level of great literature.

Surfers share their waves with sharks, but fear not

Benchley’s novel lingers longer

One of the outcomes of Jaws was at least a couple of generations of people who, if not exactly afraid to go back in the water, had a tendency to hum the film’s theme to themselves when wading into the surf alone.

Benchley, horrified by the bad rap his novel gave sharks, would go on to become an ecological activist focused on shark protection. In 2015, a shark was named after him: Etmopterus benchleyi.

Benchley’s Jaws may not immediately grab one as easily as Spielberg’s, and it’s certainly not as technically accomplished. Its position in American literature is minor compared to the film’s in Hollywood cinema.

But despite – or, perhaps, because of – its flaws, the novel is worth reading at a time when the blockbuster has virtually decimated the middle of American cinema, churning out masses of pleasurably forgettable, interchangeable films that float like a thick slick of chum on the water’s surface.