Dutch design studio Loop Loop has pioneered a process of adding colour to aluminium using pigments made from plants rather than petroleum.

Odin Visser and Charles Gateau, founders of the Rotterdam-based studio, claim to have created the “world’s first plant-based aluminium dying process”.

They have produced four bio-based pigment solutions that can be applied to aluminium through anodising, a surface treatment process that typically uses petroleum-based pigments.

Visser told Dezeen it was “the most complex issue” that Loop Loop had ever tackled.

“Natural pigments are being used more and more, but most of them are absolutely ineffective in the context of anodising,” he explained.

“We had to take a deep dive into chemistry, using resources from research papers to AI chatbots in order to understand the underlying principles that decide if a pigment is going to work or not.”

Visser and Gateau are on a mission to make the process of aluminium anodising more accessible to designers, makers and small-scale manufacturers. Currently, it is largely only used in mass production.

The long-term aim is to make their designs and recipes open source, so anyone could set up a production facility.

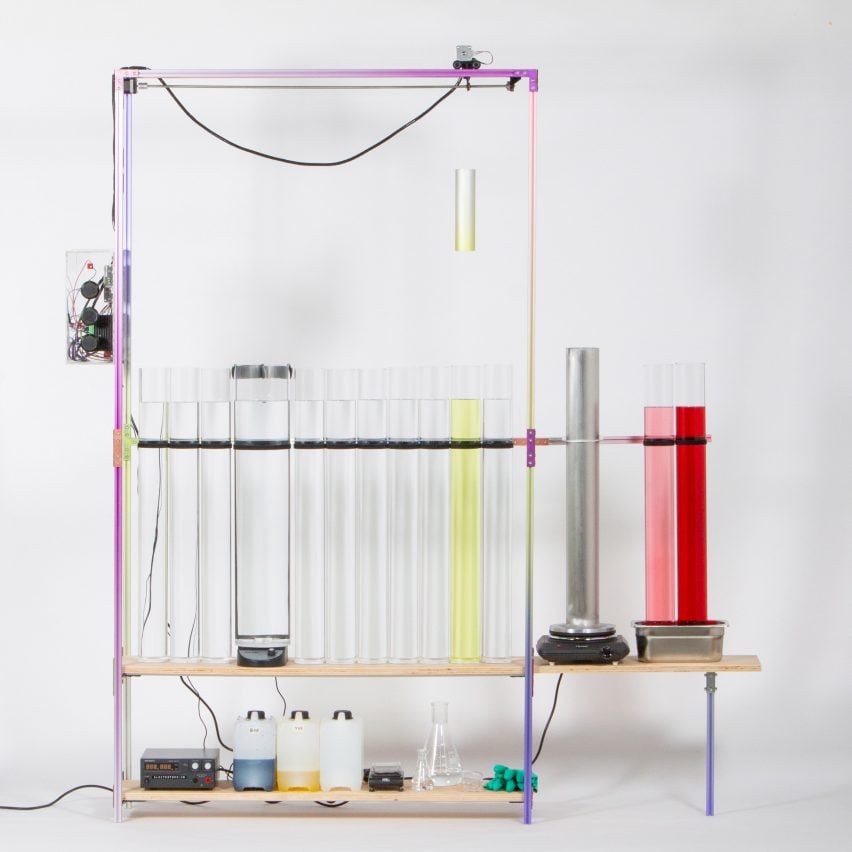

Their journey began with the Magic Colour Machine, unveiled during Milan design week in 2022. This mobile, custom-built machine was designed to allow anyone to apply colour gradients to aluminium components, wherever they are.

This new project, titled Local Colours, explores how the process could be made more sustainable.

“To find a way to produce the pigments for our Magic Colour Machine ourselves in a plant-based way helps us to further close the loop,” said Visser.

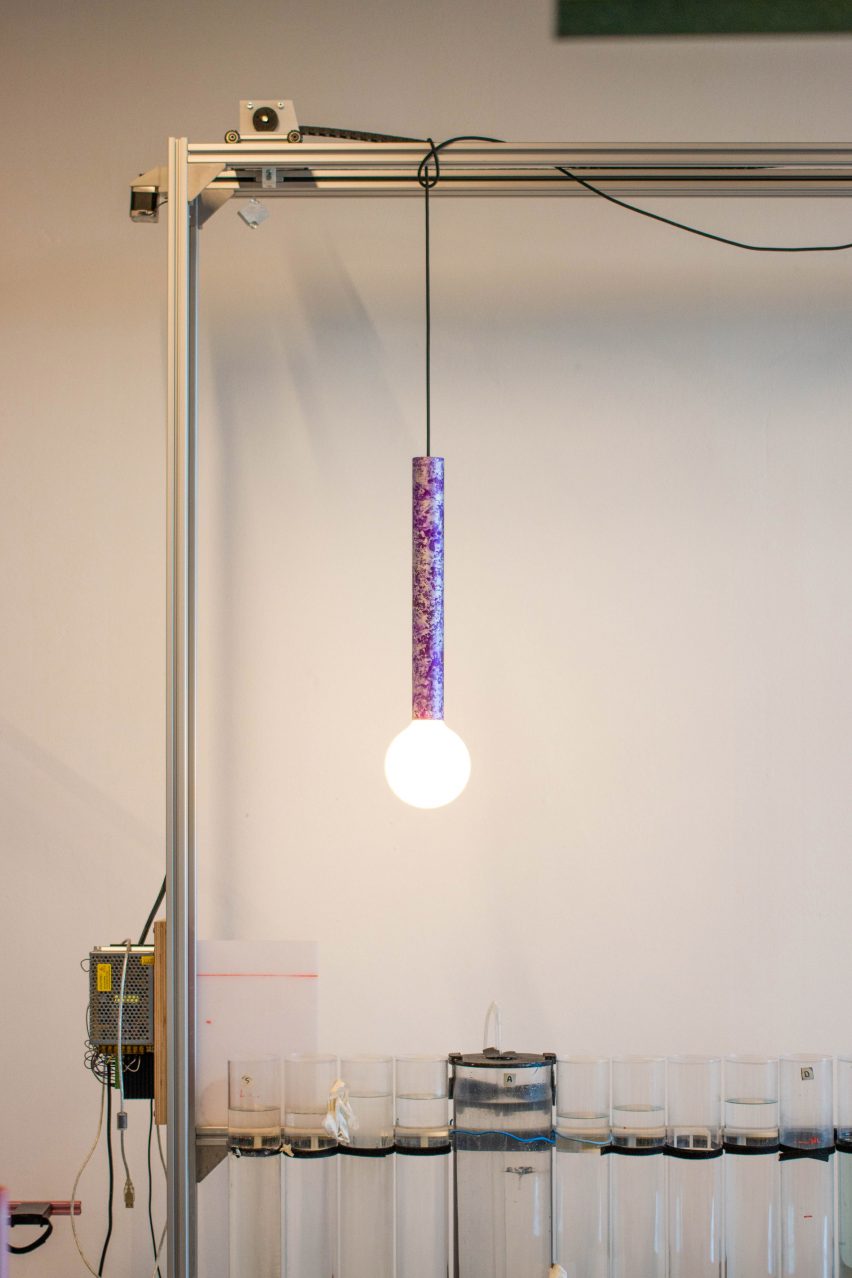

The four dyes developed so far include a warm purple derived from dyer’s alkanet flowers, a mustard yellow created with dyer’s rocket flowers, a deep pink made using madder root and a bright gold produced with red onion.

Loop Loop has explored different techniques for applying these colours to metal with different effects.

As well as smooth gradients, the pigments can be used to create textural finishes.

“The finish depends on how the pigments are applied,” explained Gateau, a Design Academy Eindhoven tutor with a background in material science.

“We can follow the standard practice of anodising and dip our pieces in a dye to obtain a uniform colour finish. In that sense, it is impossible to distinguish it from the industrial pigments,” he told Dezeen.

“It is also possible to press plant parts directly onto the surface we wish to dye; all sorts of patterns can emerge.”

The anodising process involves using an electric current to apply a thin aluminium oxide layer on the outer surface of the metal.

Loop Loop’s tests suggest that plant-based anodising finishes behave much the same as petroleum-based finishes, meaning they can be just as easily removed as added.

The main difference is that the colours react when exposed to direct sunlight.

“This is due to the molecular structure of the dyes, which is way more complex and diverse in the case of natural-based substances,” said Gateau. “The colours have a life of their own.”

Visser and Gateau have been growing their own plants for the dyes, supporting their commitment to localised production.

Once the recipes are made open source, they hope to encourage others to do the same. The ambition is to launch a platform that makes this possible in 2024.

“It’s still at an early stage, but we envision an ecosystem of designers, researchers and makers sharing the outcomes of work in the field of circular products and service systems,” added Visser.

Other designers exploring the possibilities of plant-based pigments include Nienke Hoogvliet, who has launched a brand working with seaweed-based textile dyes, and Studio Agne, which has created textile dye from biowaste.