When a hurricane hits land, the destruction can be visible for years or even decades. Less obvious, but also powerful, is the effect hurricanes have on the oceans.

In a new study, we show through real-time measurements that hurricanes don’t just churn water at the surface. They can also push heat deep into the ocean in ways that can lock it up for years and ultimately affect regions far from the storm.

Heat is the key component of this story. It has long been known that hurricanes gain their energy from warm sea surface temperatures. This heat helps moist air near the ocean surface rise like a hot air balloon and form clouds taller than Mount Everest. This is why hurricanes generally form in tropical regions.

What we discovered is that hurricanes ultimately help warm the ocean, too, by enhancing its ability to absorb and store heat. And that can have far-reaching consequences.

Kelvin Ma via Wikimedia, CC BY

When hurricanes mix heat into the ocean, that heat doesn’t just resurface in the same place. We showed how underwater waves produced by the storm can push the heat roughly four times deeper than mixing alone, sending it to a depth where the heat is trapped far from the surface. From there, deep sea currents can transport it thousands of miles. A hurricane that travels across the western Pacific Ocean and hits the Philippines could end up supplying warm water that heats up the coast of Ecuador years later.

At sea, looking for typhoons

For two months in the fall of 2018, we lived aboard the research vessel Thomas G. Thompson to record how the Philippine Sea responded to changing weather patterns. As ocean scientists, we study turbulent mixing in the ocean and hurricanes and other tropical storms that generate this turbulence.

Skies were clear and winds were calm during the first half of our experiment. But in the second half, three major typhoons – as hurricanes are known in this part of the world – stirred up the ocean.

Sally Warner

That shift allowed us to directly compare the ocean’s motions with and without the influence of the storms. In particular, we were interested in learning how turbulence below the ocean surface was helping transfer heat down into the deep ocean.

We measure ocean turbulence with an instrument called a microstructure profiler, which free-falls nearly 1,000 feet (300 meters) and uses a probe similar to a phonograph needle to measure turbulent motions of the water.

What happens when a hurricane comes through

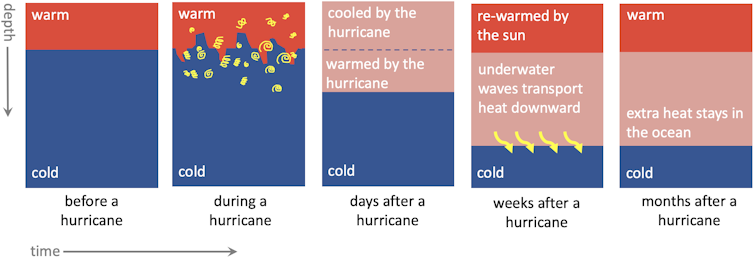

Imagine the tropical ocean before a hurricane passes over it. At the surface is a layer of warm water, warmer than 80 degrees Fahrenheit (27 degrees Celsius), that is heated by the sun and extends roughly 160 feet (50 meters) below the surface. Below it are layers of colder water.

The temperature difference between the layers keeps the waters separated and virtually unable to affect each other. You can think of it like the division between the oil and vinegar in an unshaken bottle of salad dressing.

As a hurricane passes over the tropical ocean, its strong winds help stir the boundaries between the water layers, much like someone shaking the bottle of salad dressing. In the process, cold deep water is mixed up from below and warm surface water is mixed downward. This causes surface temperatures to cool, allowing the ocean to absorb heat more efficiently than usual in the days after a hurricane.

For over two decades, scientists have debated whether the warm waters that are mixed downward by hurricanes could heat ocean currents and thereby shape global climate patterns. At the heart of this question was whether hurricanes could pump heat deep enough so that it stays in the ocean for years.

Sally Warner, CC BY-ND

By analyzing subsurface ocean measurements taken before and after three hurricanes, we found that underwater waves transport heat roughly four times deeper into the ocean than direct mixing during the hurricane. These waves, which are generated by the hurricane itself, transport the heat deep enough that it cannot be easily released back into the atmosphere.

Implications of heat in the deep ocean

Once this heat is picked up by large-scale ocean currents, it can be transported to distant parts of the ocean.

The heat injected by the typhoons we studied in the Philippine Sea may have flowed to the coasts of Ecuador or California, following current patterns that carry water from west to east across the equatorial Pacific.

At this point, the heat may be mixed back up to the surface by a combination of shoaling currents, upwelling and turbulent mixing. Once the heat is close to the surface again, it can warm the local climate and affect ecosystems.

For instance, coral reefs are particularly sensitive to extended periods of heat stress. El Niño events are the typical culprit behind coral bleaching in Ecuador, but the excess heat from the hurricanes that we observed may contribute to stressed reefs and bleached coral far from where the storms appeared.

James Watt via NOAA

It is also possible that the excess heat from hurricanes stays within the ocean for decades or more without returning to the surface. This would actually have a mitigating impact on climate change.

As hurricanes redistribute heat from the ocean surface to greater depths, they can help to slow down warming of the Earth’s atmosphere by keeping the heat sequestered in the ocean.

Scientists have long thought of hurricanes as extreme events fueled by ocean heat and shaped by the Earth’s climate. Our findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, add a new dimension to this problem by showing that the interactions go both ways — hurricanes themselves have the ability to heat up the ocean and shape the Earth’s climate.