The story of Britain’s Black publishers is one of endurance and monumental creativity in the face of repeated attempts at persecution and denigration.

Luminaries such as the authors and intellectuals C.L.R. James and George Padmore had been educated in some of the Caribbean’s elite colonial schools. There, they were subject to a formal education of respect for English culture and, above all, the monarchy.

Yet as they travelled to Britain in the 1930s, these writers and activists went on to author and publish fervent critiques of the imperial system in which they had been raised. They were followed by scores of students and workers throughout the 1950s – the so-called Windrush generation – like the publishers Eric and Jessica Huntley who, although often subject to that same imperial education, continued in this tradition of anti-colonialism.

This article is part of our Windrush 75 series, which marks the 75th anniversary of the HMT Empire Windrush arriving in Britain. The stories in this series explore the history and impact of the hundreds of passengers who disembarked to help rebuild after the second world war.

Many of these Caribbean migrants settled in the same locations to establish nascent Black communities and neighbourhoods around the country, including Paddington and Haringey in London, Handsworth in Birmingham, and Tiger Bay in Cardiff. Through neighbourhood newsletters, new arrivals learned how to navigate Britain’s seemingly hostile environment.

The practice of self-publishing had long been undertaken in the Caribbean islands, often acting as a mouthpiece for debating societies. In Paddington, a community-produced newsletter informed Black newcomers of the shops, clubs and bars in the area that were most welcoming.

Like much Black-produced ephemera throughout the 20th century in both Britain and the Caribbean, this newsletter would have been put together in local cafes, newsagents and living rooms by pen and typewriter, then printed on hand-mechanised Gestetner machines before being made available in the local district.

This was an introverted, communal process in which readers and writers were often one and the same. Through such newsletters, a keen and distinct cultural and political Black identity was cultivated.

From activists to publishers

Out of this long Caribbean tradition of do-it-yourself publishing, two publishers emerged to change the face of the nascent Black British publishing scene.

The bookshops-turned-publishing houses, New Beacon (est. 1966) and Bogle-L’Ouverture (est. 1969), offered Black writers the opportunity to publish lengthier works of literature and scholarship.

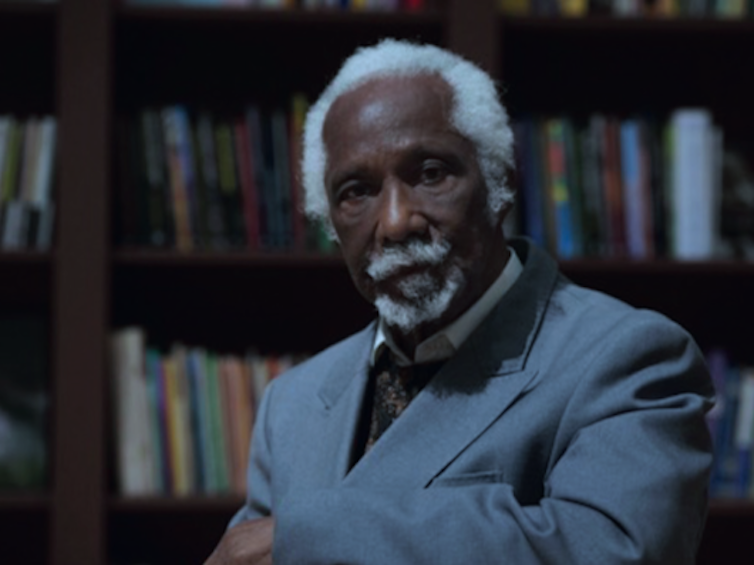

Rod Westmaas, Author provided (no reuse)

In many respects, the reasons for establishing Black publishers were made urgent due to the rejection of Caribbean people and their culture in Britain. They were subject to police harassment in the form of the Sus laws, which allowed police to arrest any “suspected person”. Their children were systematically marginalised in their education. And cultural venues like the Bogle-L’Ouverture bookshop were firebombed by far-right racists. There was a simmering feeling of persecution and rejection from the British nation among the Caribbean diaspora.

Between them, Bogle-L’Ouverture and New Beacon printed forceful critiques of the British colonial system and the insidious everyday experiences of racism in Britain. Works such as Walter Rodney’s How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (1972, Bogle-L’Ouverture) and Bernard Coard’s How the Caribbean Child Was Made Educationally Subnormal (1971, New Beacon) remain cornerstone reading for scholars of Black studies and Black British history.

In this commitment to promoting the Black cultural scene, John La Rose (who established New Beacon) created the Caribbean Artists Movement in 1966. This forum spearheaded the work of literary critics, poets, scholars and artists such as Aubrey Williams, Kamau Brathwaite and Linton Kwesi Johnson.

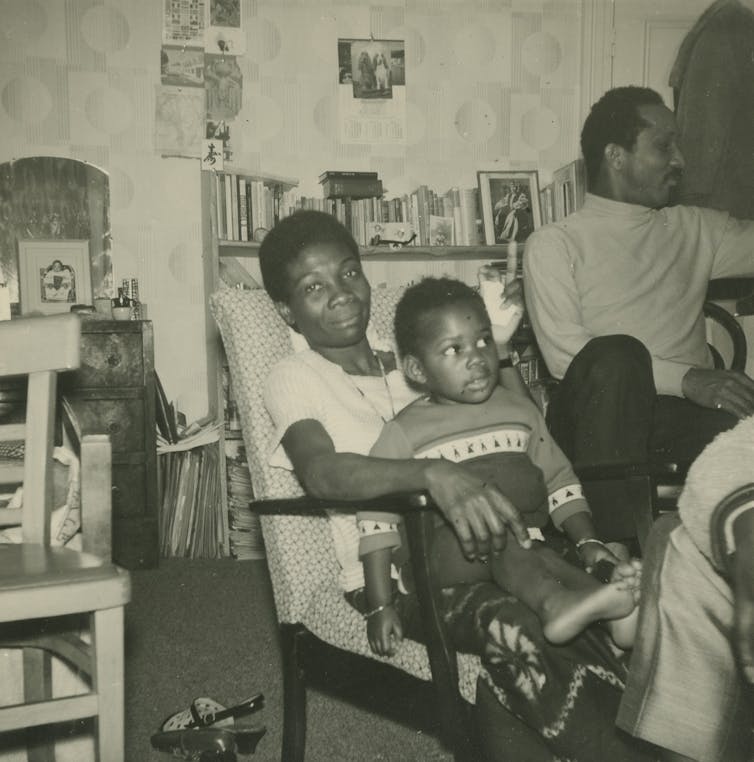

Courtesy of Michael McMillan/Huntley Archives at London Metropolitan Archives

Likewise, Eric and Jessica Huntley at Bogle-L’Ouverture hosted talks by compelling and dynamic Black speakers and thinkers such as Angela Davis and Valerie Bloom.

These publishers were rooted in the communities they served, augmenting and fostering a sense of Blackness as an artistic expression as well as a political force, rather than as being a marker of any sort of racial inferiority. Through their work, they encouraged pride in Caribbean, African and, at times, south Asian culture.

Although wholly self-reliant and deeply interpersonal like the smaller initiatives that preceded them, these publishers ushered in a new era of pan-African and Black British identity.

They catered to an emerging national market of Black and British readers who desired to understand better their own plight in the “Motherland”. And as these readers often sent works back to east and west Africa, north America and the Caribbean, they became nodal points in an international network of intellectuals and writers.

Although these publishers were by no means the only players in this multifaceted history, they are a burning example of the people of the Windrush, who not only persevered through a hostile environment but generated new cultural and artistic expressions.

The burgeoning different Black artforms in this era laid the foundation for the explosion of Black media – and the proliferation of the self-assured Black British identity – that emerged on screens, radio and in print from the 1990s onwards.