Note of warning: This article refers to deceased Aboriginal people, their words, names and images. Words attributed to them and images in the article are already in the public domain. Also, historical language is used in this article that may cause offence. Individuals and communities should be warned that they may read or see things in this article that could cause distress.

In the breakthrough High Court case Love and Thoms vs Commonwealth in 2020, the court ruled that First Nations people could not be considered aliens in Australia. As Justice James Edelman noted in the decision,

whatever the other manners in which they were treated […] Aboriginal people were not ‘considered as foreigners in a kingdom which is their own’.

Yet, in my upcoming book with historian Kate Bagnall, I look at how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were long denied the rights of citizenship in their own land due to discriminatory laws – perhaps no more so than in Western Australia.

Until the 1970s, Western Australia still forced Aboriginal people to “dissolve tribal and native associations” and “adopt the manner and habits of civilised life” for two years before they could apply for citizenship under the state’s Natives (Citizenship Rights) Act 1944

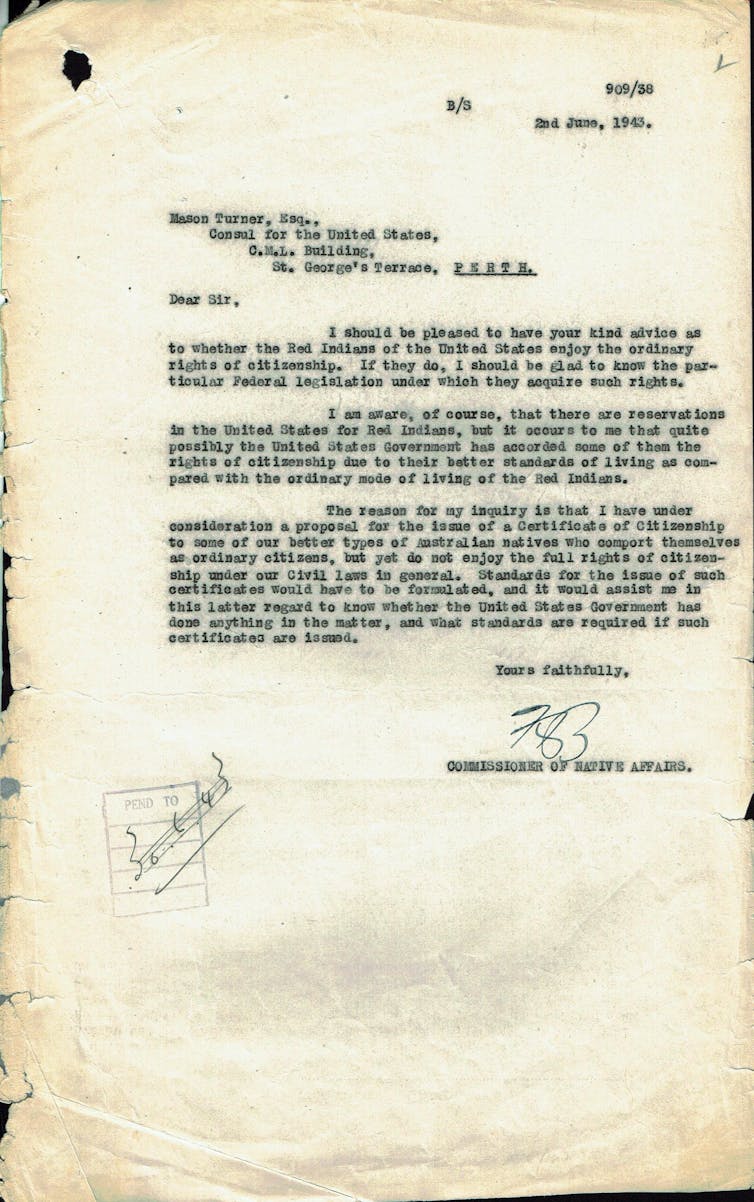

Western Australia had copied racially discriminatory provisions on citizenship from the United States, specifically the outdated 1918 US Federal Code, with strong echoes of the notorious “Black Laws” from the early 1800s.

State Records Office of Western Australia

As Garth Nettheim and Larissa Behrendt note in the 2010 edition of Laws of Australia, the Western Australian law “throughout its life was inconsistent with the Commonwealth legislation” and therefore unlawful.

This is because, from the time of federation, nationality and citizenship were matters for federal, not state law.

Under British law that had remained unchanged since the 17th century, all Aboriginal Australians were already considered British subjects under colonial rule. And in 1948, the Nationality and Citizenship Act gave citizenship to all Australians previously deemed British subjects, including Aboriginal people.

Noongar activists knew they were already citizens under the laws imposed by white settlers and called for the rights and protections that should have been granted to them.

As George Abdullah, founder of the Aboriginal Advancement Council of WA and president of the Aboriginal Rights Council, said in 1962:

Full Australian citizenship was the natives’ birthright, but even the most degraded white Australian had more rights than the native. To deprive a person of civil rights was to destroy his self-esteem and his incentive to become a responsible citizen.

Abdullah displayed the same resolve to achieve equal human rights for Aboriginal people that is evident more than 60 years later in the drive for a Voice to Parliament. He declared:

We are demanding freedom from restrictive legislation, with equal rights and opportunities as our white brothers and sisters, and then we can join them in developing a greater Australia.

Citizenship hearings more akin to criminal trials

State Records Office of Western Australia

For over a century, Australian states enforced so-called “protection laws” controlling every aspect of the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. These laws led to the forcible removal of Indigenous children from their homes and controlled everything from where people lived and worked to their personal relationships and contacts with family and community.

But only Western Australia added citizenship legislation as well, peddling the lie that Aboriginal people had to apply under state law to become “Australian citizens”. Consistent with the national policy of assimilation at the time, one white MP told the state parliament in 1944 that citizenship was an “inspirational measure” for “de-tribalised natives” who lived according to “white standards”.

Government ministers in Western Australia wilfully disregarded the laws of the Commonwealth in setting up this discriminatory system. When introducing the Natives (Citizenship Rights) bill to state parliament in September 1944, A.M. Coverley, the minister for the North-West, claimed,

The main principle underlying the bill is to provide an opportunity for adult natives to apply for full citizenship as Australians.

Wikimedia Commons

After the law was passed, “citizenship” hearings in Western Australia were more like criminal trials, held before a police magistrate with local police as witnesses. Aboriginal applicants suffered the humiliation of intrusive medical examinations and personal inspections of their homes.

The magistrate had to be satisfied the applicant was “of good behaviour and reputation” and “reasonably capable of managing his own affairs”. In addition, applicants had to be “able to speak and understand the English language” and could not be suffering from “active leprosy, syphilis, granuloma or yaws”.

Long before the Voice vote, the Australian Aboriginal Progressive Association called for parliamentary representation

Some Aboriginal residents in WA refused to take part in the intrusive process.

In 1954, for example, Noongar man George Howard, who described himself as “a Native and […] proud of that fact”, addressed a Rotary luncheon at the Savoy Hotel, Perth. His very presence in the hotel contravened a state prohibition on “natives” entering licensed premises. As Perth’s Daily News pointed out, “he could get full legal rights by getting a certificate of citizenship”. But as Howard told the audience,

to get this certificate, I must pay fees and undergo personal investigation by a board, with the end result of being told I am what I am – a natural-born Australian.

Others who went through the process were mysteriously denied, even if they satisfied all of the requirements. In 1955, Noongar man Jack Shandley, head stockman at Gogo Station near Fitzroy Crossing, travelled 300 kilometres to the Derby magistrates court, declaring he wanted “to be Australian and be free to travel”. However, his application was refused, with no reason given.

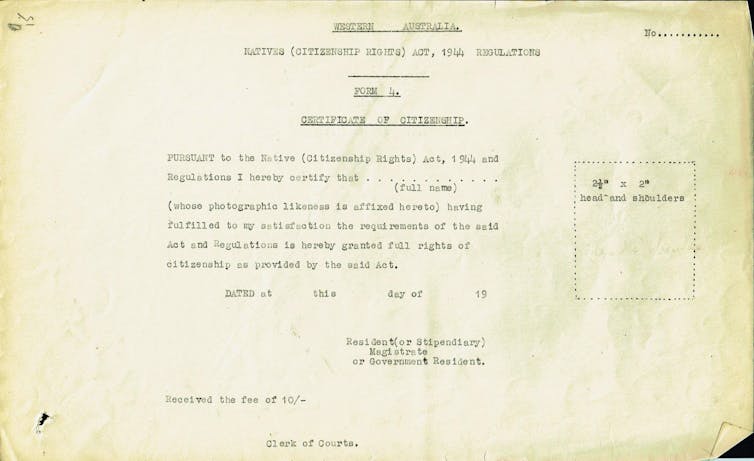

State Records Office of Western Australia

The 1881 Maloga petition: a call for self-determination and a key moment on the path to the Voice

A certificate akin to a ‘dog tag’

Even successful applicants faced increased racial harassment, not least being targeted as potential suppliers of liquor. In 1947, for instance, Police Constable C.H. Brown observed suspicious activity on Wellington Street in Perth:

I saw the native, Sport Charles Jones, holder of the certificate of citizenship No. 152 walking across the street from the direction of the Imperial Hotel. He was carrying two bottles bearing labels, which appeared to be Emu Bitter Beer Labels.

Jones was convicted and “fined £4 with 4/6 costs” for supplying beer to a “native”.

Aboriginal Australians derided their “certificate of citizenship” as a derogatory “dog licence” or “dog tag”. In 2002, Wongutha man Leo Thomas told the Federal Court:

When I was about 21 years old […] the football team would go drinking, but if I was caught getting a beer at a hotel my mate would be fined […] The president of the football club asked for me one day they said that we have to go to court […] so they ended up giving me the citizenship rights […] a little black book […] the dog collar, I used to call it.

Even former soldiers in the Australian armed forces had to show their citizenship “dog tag” to get a drink in a WA pub.

James Brennan enlisted in the army in 1940 and was one of the “Rats of Tobruk” in the second world war, a group of Australian forces who held the Libyan port of Tobruk against German-Italian forces. But as his son-in-law later related to the ABC,

When he came back from war […] he had to get a citizenship right to go into pubs […] He fought for the country and when he came back home, he couldn’t go into any hotel to get a drink.

Why truth-telling matters

Courts and policymakers are still making decisions about the lives of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples without full knowledge of Indigenous histories and how they continue to affect people today. In our forthcoming book, I argue that even Australia’s highest court has presented a misleading, “whitewashed” view of the history of Indigenous belonging since 1788.

The Voice to Parliament – and the broader goals being sought under the Uluru Statement from the Heart – now offer Australia a chance to confront its history and construct a more inclusive narrative of nationhood.

This history should address the ways in which Australia’s First Peoples were refused equal citizenship and denied the rights and protections that should have accompanied that status. Western Australia’s citizenship law must not be forgotten – it’s an integral part of this story.