For more than three decades, Moscow and Beijing have been incrementally strengthening their partnership. The growing number of potentially conflicting interests, for instance over investment and exploration in the Arctic, have not slowed down cooperation.

Despite Russia becoming China’s “junior partner” over the last decade as Beijing’s economic and global strength has grown, their relationship remains strong. Pushing back against US power is a continual driver for both nations.

But if Russian president Vladimir Putin was no longer in a leadership role would the relationship unravel? A change of leadership in Moscow is likely to complicate Russian-Chinese cooperation, but not due to ideological shifts in Russian politics or geopolitical realignments on the global scene.

The prospects for Russia’s democratisation or improvement in relations with the west are the bleakest in the last two decades. It is Russian domestic politics that is most likely to play a significant role in affecting the direction of the future relationship of the two countries.

Any change in the Kremlin is likely to upset a delicate balance in Russia’s political and economic ecosystem and would lead to a new round of internal struggles for influence and resources.

While deepening cooperation with Beijing, Moscow has signed a number of agreements, which were sub-optimal from the perspective of the Russian state but which strengthened the positions of Putin’s allies and associates.

In return, they created a powerful pro-Chinese lobby in the corridors of the Kremlin. Without Putin’s patronage, these business empires could be targeted by those surrounding a new leader, if they wanted to move into having more diverse business partners abroad.

What’s more, those Russians who have supported ever closer cooperation with China cannot be taken for granted. If China decided to employ wolf-warrior diplomacy (a confrontational technique that pushes back against criticism of the Beijing government) in Russia it could alienate those who were previously allies.

Some Russian scholars warned of this even before the war in Ukraine. An escalation of Chinese cyber, industrial and traditional espionage practices – a temptation that may be irresistible for a stronger partner – would push Russian intelligence services to crack down on Chinese technology with possible surveillance capabilities.

A new leader would have an opportunity to reassess the degree of Russia’s dependence on China and the broader context of Russian policy in Asia. It is worth remembering that already in the mid-2000s, Russia was trying to make a “turn to the east”, not a turn to China.

Russia’s Asian policy was to be balanced and diversified, focused on cooperation with China, Japan, Korean states and south-east Asian countries. Oil and gas pipelines were meant to serve Asian customers, not just China.

Putin under pressure: the military melodrama between the Wagner group and Russia’s armed forces

Meanwhile, China has been buying the lion’s share of the oil sent to Russia’s Asian terminal in Kozmino. The Power of Siberia gas pipeline and its potential second branch go only to China and thus make it impossible for Russia to start exporting gas directly to other customers such as South Korea.

The participation of Russian aircraft and ships in joint patrols around Japan is beneficial to Beijing, but it limits Moscow’s room for manoeuvre to forge other Asian allies and makes it dependent on Chinese policy.

Domestic opinion

Domestic politics in Russia has created favourable conditions for close cooperation with China. But regime survival considerations affect the Kremlin’s assessment of China’s growing power and lead it to neglect the growing asymmetry in relations with Beijing.

The Russian elite does not see China as a threat to the security and survival of the regime. Therefore, it is easier for Moscow to interpret China’s rise to a superpower as friendly and to accept its growing global role, even if it makes Russia a less significant partner.

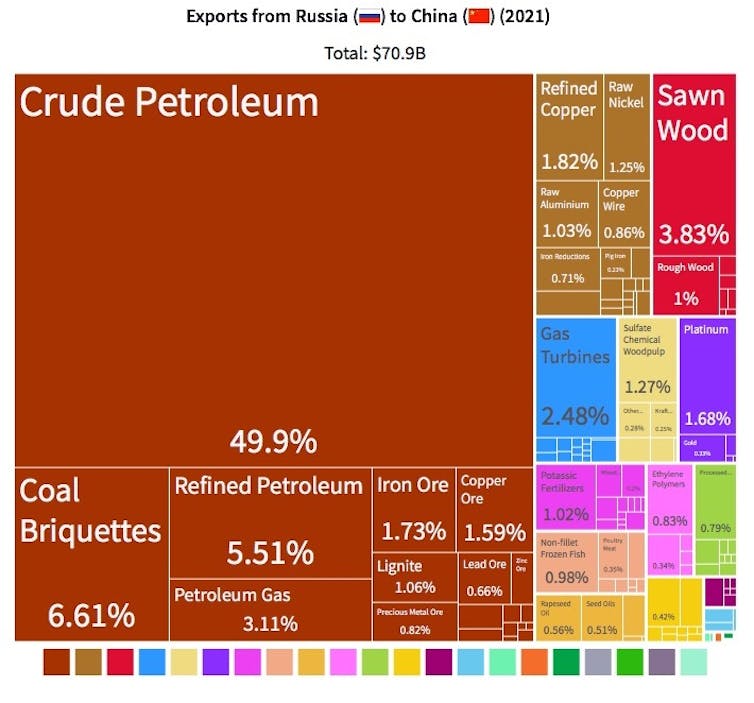

OEC

The financial and political benefits gained from the partnership by individual members of the Russian elite have been another driver for the relationship with Beijing. Not everyone is as enthusiastic about cooperation as Igor Sechin, head of state-owned oil firm Rosneft, for whom China is the most important partner.

However, even those companies who compete with their Chinese counterparts, such as Russia’s state nuclear energy corporation Rosatom, still benefit from having a presence on the Chinese market.

Without a doubt, a new Russian leader’s hands would be tied to a large extent. Oil and gas pipelines leading to China connect Russian companies with this market and cannot be replaced easily. The selective support offered by China has consolidated the pro-Beijing orientation of the key players in Russia.

Even before the war in Ukraine, Beijing helped some companies circumvent the barriers from western sanctions by offering prepayments for oil deliveries or providing loans. A large part of the Russian elite sees China as the only partner against the west.

Nevertheless, any new leader will have an opportunity to re-evaluate the costs and benefits of close ties with Beijing, and it will be in their interest to do so, if it can strengthen its hand.