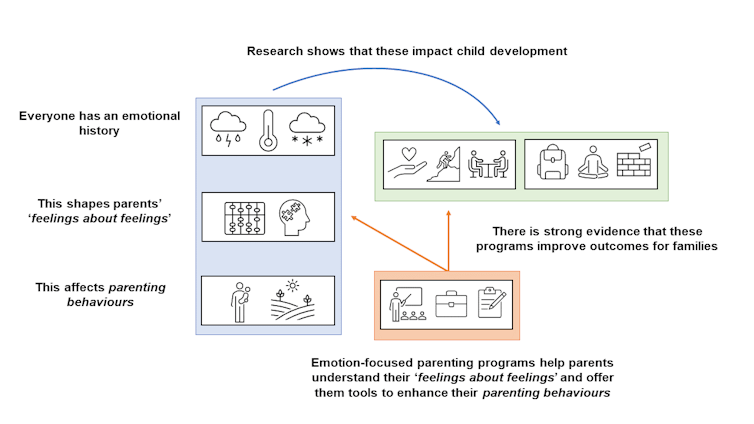

How our families express feelings, talk about feelings and react to feelings can have ripple effects into the next generation.

When someone becomes a parent, the models they had can become embedded in how they in turn parent.

A parent’s organized set of thoughts and feelings about their own and their child’s feelings is what some psychologists call “parental meta-emotion philosophy.” Understanding this can make a big difference in parenting and children’s development.

I lead research projects that investigate the usefulness of programs that teach parents how to understand their “feelings about feelings” and guide their children in healthy emotional regulation and coping strategies.

The family emotional climate

All of us have a long emotional history that comes from the emotional climate we grew up with. Early experiences become ingrained in how we feel about feelings, and affect our ability to form healthy relationships.

How parents can be ’emotion coaches’ as kids navigate back-to-school during COVID-19

Based on their emotional history, some parents become good at what psychologists call emotion coaching.

These parents have learned to recognize and accept their feelings, for example that “it is okay to be sad.” They are aware of their children’s lower-intensity feelings and view their children’s emotional displays as a time for connection and teaching.

(Shutterstock)

Becoming aware of feelings

Other parents have learned to ignore or deny their feelings and develop a tendency to dismiss emotions. These parents tend to avoid uncomfortable feelings like sadness and anger. Emotionally dismissive parents will likely try to make uncomfortable feelings in children go away quickly or brush them off by saying things like “you’ll get over it.”

Gaining the ability to be aware of, understand and manage feelings is an important part of child development. Studies have shown that parents who have an “emotion coaching” philosophy support their children’s emotional regulation, behaviour and social skills.

The question is, how effective is teaching parents to understand their “feelings about feelings” at improving the family emotional climate and child development outcomes.

Parenting programs

Parent education programs teach parents about children’s needs and development and offer them tools to enhance their parenting behaviours. Some parenting classes and programs are delivered through organizations like family centres and social services.

Others are offered through medical clinics like pediatricians’ offices. There are many programs that help parents respond to children’s challenging behaviours — for example, teaching parents how to positively reinforce children’s appropriate behaviours.

(Gillian England-Mason), Author provided

More recently, some parenting programs have begun to focus on parents’ feelings about feelings: emotion-focused parenting programs. These programs teach parents specific parenting behaviours that support their children’s emotional needs.

One such program is called Tuning in to Kids. It was developed in Australia and teaches parents how to become “emotion coaches” who emotionally connect with their children, label and validate their children’s feelings, and help their children solve problems.

Another example is the Emotional Development version of Parent-Child Interaction Therapy, which strengthens relationships and teaches parents how to help their children regulate emotions.

Tailored parenting programs

In research with my colleagues, Krysta Andrews, Leslie Atkinson and Andrea Gonzalez, I have examined the effectiveness of emotion-focused programs in a recently published article in Clinical Psychology Review. This article provides strong evidence that emotion-focused parenting programs can enhance parents’ ability to positively socialize their children’s emotional development and maximize positive outcomes for families.

However, there is a need for families, researchers, clinicians and early childhood development policymakers to work together to find out what programs work best, when and for whom.

Some of my work suggests that these programs may especially benefit children and adolescents with complex needs, such as co-occurring mental health problems and neurodevelopmental disorders like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Treating specific symptoms of autism or ADHD can help children, even without a diagnosis

Children under two, culturally appropriate programs

Some of my research indicates that emotion-focused parenting programs should be adapted or developed for specific populations. For example, for parents of children under age two, as this age is a period of vulnerability for long-lasting emotional and behavioural problems.

And, the way families “feel about feelings” is also influenced by social determinants of health, which include socioeconomic factors like culture, racialization, education, housing and income. This suggests that programs for parents of children of different ages should also be culturally appropriate. Emotion-focused programs should be adapted to serve a diversity of caregivers, family structures and backgrounds.

(Pexels/Laura Garcia)

Effects on biology

Parenting is a biological process — hormones, brain regions and chemical messengers in the brain all support parenting behaviours. Programs that focus on parental meta-emotion philosophy have the groundbreaking ability to change parenting on a behavioural level, but also on a biological level.

Psychology researchers have reason to think that helping parents understand their “feelings about feelings” can change children’s biology. One study found that program content on emotion development was uniquely related to positive changes in emotion-related parenting and children’s brain signals.

It is possible that these behavioural and biological changes can be passed on across generations.

Families with parents who understand their “feelings about feelings” will have a positive emotional change now and possibly into future generations.