There are numerous factors that influence public trust in government, one in particular is the relationship with people in power and lobby groups. Some of the recent scandals that have damaged public trust in British politics have related to people with private financial interests having far more access to politicians than we might like – and with people connected to politicians getting special treatment.

Most special advisers, who act as senior advisers to ministers in government, are supposed to wait two years before taking a job lobbying government for a new employer but this rule is rarely enforced.

There is a general sense that the revolving door between politics and the world of lobbying spins a little too fast these days.

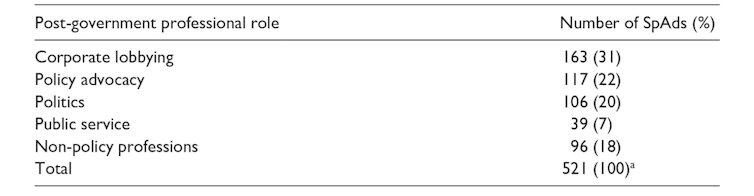

In new research, we looked at just how fast by conducting a study on the post-government career moves of 521 former British special advisers who served ministers from 1997 to 2017. The goal was to see how many ended up in corporate lobbying jobs. And indeed, most did.

What is a special adviser?

UK special advisers are powerful political figures in Whitehall. They are senior political staff who are personally appointed by a minister to advise them on policy and politics. They work on temporary contracts and are not classed as civil servants – who are nonpartisan government employees.

The total number of special advisers working in Westminster remains small, but has grown substantially from around 38 under former British prime minister John Major in 1996 to 125 under Boris Johnson in 2022. However, their ability to influence British politics endures even after they leave government so these figures remain important.

From public to private sector

Our study of special advisers found that 31% moved into corporate lobbying after leaving government.

Some went to work for registered lobby firms, which are contracted by various different companies to influence decision makers.

Alamy

Others got jobs in government relations doing influencing on behalf of internet companies, food and drinks producers and for banking and insurance firms.

Professional lobbying firms have to list themselves on the Register of Consultant Lobbyists but in-house lobbyists employed directly by companies or organisations don’t. Almost all special advisers in our sample, irrespective of type of corporate organisation they revolved into, work without being registered as a lobbyist in the official registry.

Another 22% went into policy advocacy, taking jobs representing the interests of trade unions, thinktanks and charities or working for organisations dedicated to a specific cause.

Policy advocates are also considered to be lobbyists, despite the fact that they work for different kinds of clients and may have different ideals than corporate types.

Therefore, around 54% of former special advisers revolve into some kind of broadly defined lobbying role after they leave government.

The post-government life of special advisers, 1997-2017

Author provided, Author provided (no reuse)

Why it matters

On balance, former special advisers who have since moved into lobbying roles help ensure important causes reach the ears of decision makers. As independent advisory group the Committee on Standards in Public Life recognised, “lobbying is an important and legitimate aspect of public life in a liberal democracy”.

But lobbyists have more capacity to influence policy compared to the general public. And that is even more true for people who recently worked in government themselves. They have established political networks, an understanding of the machinery of government and corporate interests backing them. They can use their contacts from their former job to excel in their new role. They may find it easier to get a meeting with a minister of senior decision maker or get them to attend their events, for example.

EPA/Soeren Stache.

Lax transparency standards are partly to blame for how quickly many special advisers become lobbyists. It is hard to know who is a lobbyist and who is not.

By improving transparency measures, more people would have faith in the process by which decisions are made and public policies are crafted.