“Love” is the first word in Ariel, the collection of poems published by Faber and Faber in 1965 that made Sylvia Plath one of the most famous poets of the post-war generation.

In many ways, Ariel, as Plath conceived it, is all about love. In the “restored” Ariel – the original manuscript that Sylvia Plath left on the desk of her London flat before her death – the word “love” recurs over 25 times.

After the “lies, lies, and a grief” in The Couriers, there also is “love, love, my season”.

Plath never saw Ariel’s success. In the early hours of February 11 1963, during one of the coldest winters for decades, she took her own life. She had been suffering from a severe depression, compounded by mismanagement of her medication and the breakdown of her marriage to the poet Ted Hughes.

She left a manuscript of poems titled Ariel and 19 other poems, 13 of which she had written in the last weeks of her life.

In editing and publishing the 1965 collection, Hughes rearranged Plath’s original manuscript, taking out what he felt to be weaker poems and including the best of the last 19. The Ariel most readers came to know is a far darker collection than Plath intended, troubled by her breakdown and impending suicide.

This had a significant impact on how Plath’s work was read in the years after her death and how the myth of Plath as “high priestess of poetry, obsessed with death” was created.

A new generation of scholars have begun unpacking the immense complexity of Plath’s writings, emphasising her political, historical and environmental interests and her importance for women writers.

Ariel’s opening poem, Morning Song, addresses a child at the moment of its birth. The child takes centre stage in this secular nativity until it finds its voice, and “The clear vowels rise like balloons”. In Ariel, Plath marked herself out as one of the first great poets of motherhood, setting out on a path others would follow.

The importance of Ariel’s title

In her manuscript, Plath had scored out several possible titles before she settled on Ariel. Ariel is the spirit imprisoned and freed by Prospero in Shakespeare’s play The Tempest, a major inspiration for Plath.

Everett Collection Inc / Alamy Stock Photo

Ariel is also the name of a horse Sylvia rides in an early draft of the titular poem, which she describes as “of my colour”. Plath’s natural hair colour was light reddish brown, the colour of “God’s lioness”.

The titular Ariel – too often read as a kind of suicide note – is a poem of transcendence that moves towards the freedom of a new life. The “dead hands, dead stringencies” have been shucked off in the rider’s flight, and bursts out of the darkness, becoming one with the animal (the horse is often associated with poetry).

Reading the “restored” as opposed to the 1965 Ariel, is a very different experience – one of hope after the struggle of winter, to the new life of spring.

Plath’s “bee poems”, the final sequence in the restored Ariel, end with the word “spring” and images of transformation and rebirth are used throughout the collection. Lady Lazarus will rise from the ashes “one year in every ten”. In The Night Dances, the baby in the cot inspires the mother to a planetary transcendence. Poppies in October are “a gift, a love gift”. In Letter in November, there is “Green in the air”.

Ariel’s darkness

Plath remains one of the great poets of depression, fearlessly encountering her mental suffering in poems such as Elm – “I know the bottom […] I do not fear it; I have been there” and The Moon and the Yew Tree, where the moon is “quiet / With the O-gape of complete despair.”

Sylvia Plath is also a poet of protest and her fury against a world dominated by men finds expression in a group of poems in the restored Ariel. There’s The Rabbit Catcher, The Detective and my personal favourite, The Courage of Shutting Up, which was omitted from Hughes’ 1965 edition.

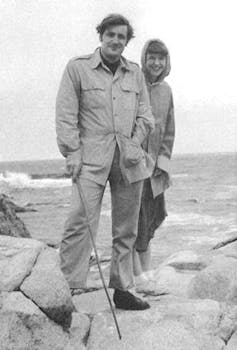

Archive PL / Alamy Stock Photo

While some of Hughes’ editorial omissions were wise – weaker poems, poems that might offend – one of his greatest mistakes was obscuring the political and burgeoning feminist aspects of Plath’s writing.

Plath died on the eve of second wave feminism (Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique was published just five days after her death). Her poetry, however, was quickly taken up as an important expression of the feminist movement and her novel, The Bell Jar, found context as an essential critique of women’s place in post-war society.

It’s important to stress that one version of Ariel does not cancel out the other. Read alongside each other they create a different picture of Plath’s poetry – bigger, more complex and with a greater power to transform.

Sylvia Plath remains one of the few poets whose work reveals itself in new ways every time you encounter it and her power to speak to each new generation only becomes greater.